Impact Factor

ISSN: 1449-1907

Int J Med Sci 2026; 23(3):1015-1032. doi:10.7150/ijms.123727 This issue Cite

Review

Gene Mutations and Related Molecular Events in Distant Metastasis of Cervical Cancer: A Review

Weifang People's Hospital, Shandong Second Medical University, Weifang, Shandong 261000, China.

† These authors contributed equally to this work.

Received 2025-8-14; Accepted 2026-1-20; Published 2026-2-11

Abstract

Cervical cancer, a serious gynecological malignancy, often leads to poor patient prognosis due to distant metastasis. The metastasis mechanism is not fully understood. This study explores the link between gene mutations and distant metastasis in cervical cancer. PDGFRA, TP53, and PIK3CA mutations significantly influence metastasis. Despite its low incidence, PDGFRA mutation is closely tied to lymph node and distant metastasis. TP53 mutation disrupts p53 protein function, promoting tumor cell proliferation, inhibiting apoptosis, and enhancing metastasis. PIK3CA mutation activates the PI3K/Akt pathway, stimulating cell proliferation and migration. Detecting these mutations is crucial for diagnosing distant metastasis. It helps identify high-risk patients early, improving diagnostic accuracy and specificity, and guiding clinical treatment decisions. Targeted therapies for PDGFRA and PIK3CA mutations can control tumor growth and metastasis but face challenges like drug resistance and high costs. This study offers a new theoretical basis and treatment strategy for cervical cancer, pointing to future research directions. Gene mutation detection enhances early identification of high-risk patients, improving diagnostic accuracy. Targeted therapies for PDGFRA and PIK3CA mutations control tumor growth but face drug resistance and cost issues. This study provides a new theoretical basis and treatment strategy for cervical cancer, guiding future research.

Keywords: Cervical cancer, Distant metastasis, Gene mutation, Targeted therapy, HPV integration, microenvironment, epigenetics

Introduction

Cervical cancer (CC) is a major public health concern, ranking as the fourth most common cancer globally in terms of both incidence and mortality among women, with an estimated 660,000 new cases and 350,000 deaths worldwide in 2022, accounting for 22.8 % and 16.0 % of incidence and mortality rates of the global rate, respectively (1). Its incidence rate ranks fourth among female malignant tumors, and its mortality rate also ranks fourth (2). In developing countries, the disease burden of cervical cancer is heavier, with higher morbidity and mortality, which seriously affects women's quality of life and health (3).

Cervical cancer is also a public health issue that cannot be ignored. The incidence of cervical cancer is showing a trend of younger people, which has placed a heavy burden on society and families (4). With the continuous advancement of medical technology, the diagnosis and treatment of early cervical cancer have made significant progress, and the survival rate and quality of life of patients have been improved to a certain extent. However, for patients with cervical cancer with distant metastasis, the prognosis is still extremely poor.

Distant metastasis is a key factor leading to poor prognosis in patients with cervical cancer (5). Once cancer cells metastasize to distant organs, such as the lungs, liver, bones, and brain, not only will the difficulty of treatment increase significantly, but the patient's 5-year survival rate will also drop significantly to only about 10%-15% (6). Patients with cervical cancer that develops distant metastasis often need to receive more complex and intensive treatments, such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy, targeted therapy (7). These treatments not only bring heavy physical burden and psychological pressure to patients, but also lead to a substantial increase in medical expenses, bringing heavy economic burden to families and society.

At present, the mechanism of distant metastasis of cervical cancer has not been fully clarified. In-depth research on the mechanism of distant metastasis of cervical cancer and finding effective predictive markers and therapeutic targets are of great significance for improving the prognosis of cervical cancer patients. Gene mutation plays a key role in the occurrence, development and metastasis of tumors. Studies have shown that multiple gene mutations are closely related to distant metastasis of cervical cancer (8). Therefore, this study aims to explore the relationship between gene mutation and distant metastasis of cervical cancer and provide new theoretical basis and treatment strategies for the prevention and treatment of cervical cancer.

Metastatic Pathways of Cervical Cancer

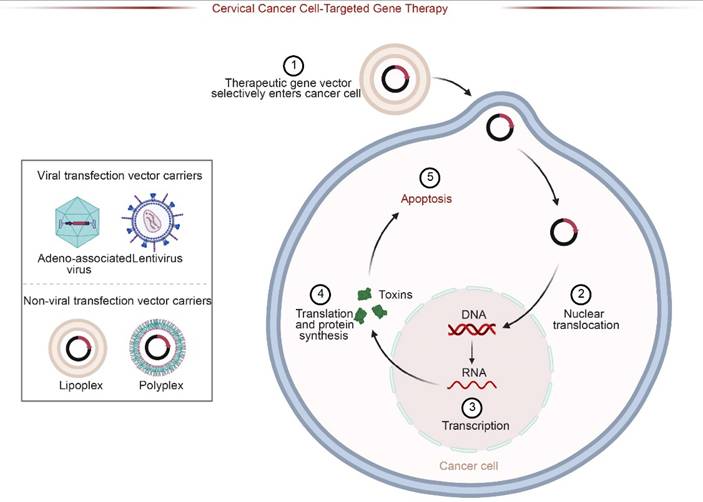

Cervical cancer is a malignant tumor that seriously threatens women's health. Its metastasis pathways mainly include direct spread, lymphatic metastasis and hematogenous metastasis (5). Different metastatic pathways play different roles in the development of cervical cancer and have an important impact on the progression and prognosis of patients.

Direct spread

Direct spread is the most common mode of metastasis of cervical cancer, accounting for about 70%-80% of all metastatic cases (9) (Figure 1A). Cancer cells can directly invade adjacent tissues and organs, such as spreading downward to the vaginal wall, causing irregular vaginal bleeding, increased secretions, etc.; they can also spread upward to the uterine cavity, causing complications such as endometritis and pyometra (10). It invades the main ligaments and paracervical and paravaginal tissues on both sides, and even to the pelvic wall, causing lumbosacral pain, lower limb edema, etc. In the late stage, cancer cells may also invade the bladder forward, causing urinary system symptoms such as frequent urination, urgency, pain, and hematuria; and invade the rectum backward, causing intestinal symptoms such as constipation, bloody stools, and tenesmus. The scope and degree of direct spread are closely related to factors such as the size, location, and degree of differentiation of the tumor. The larger the tumor, the closer it is to the surrounding tissues and organs, and the lower the degree of differentiation, the higher the risk of direct spread.

Lymphatic metastasis

Lymphatic metastasis is one of the common metastatic pathways of cervical cancer, accounting for about 20%-30% of all metastatic cases (11) (Figure 1A). When the cancer invades the lymphatic vessels, the cancer cells will enter the local lymph nodes along with the lymph fluid (12). Lymphatic metastasis of cervical cancer usually first affects the first-level lymph nodes, including parauterine, obturator, internal iliac, external iliac, common iliac, and presacral lymph nodes (13). These lymph nodes are located in the pelvic cavity and are the first stop for lymphatic metastasis of cervical cancer (14). If the disease progresses further, cancer cells will metastasize to the secondary lymph nodes, such as the deep and superficial inguinal lymph nodes, para-aortic lymph nodes (15). The occurrence of lymph node metastasis is related to factors such as tumor stage, pathological type, and degree of differentiation of tumor cells. The later the tumor stage, the more adenocarcinoma or undifferentiated carcinoma the pathological type, and the less differentiated the tumor cells are, the greater the possibility of lymph node metastasis (Figure 1B).

Hematogenous metastasis

Hematogenous metastasis is relatively uncommon in cervical cancer, accounting for only 5%-10% of all metastatic cases (16) (Figure 1A). Usually occurs in the late stage of cervical cancer, cancer cells spread through the blood circulation to various organs throughout the body, such as the lungs, liver, bones, brain (17). The occurrence of hematogenous metastasis is closely related to the biological characteristics of tumor cells, the body's immune status, angiogenesis and other factors. Tumor cells have strong invasion and migration capabilities, the body's immune function is low, and there is abundant angiogenesis in tumor tissue, which may increase the risk of hematogenous metastasis (18). When cervical cancer metastasizes through the blood, the patient will experience symptoms of the corresponding metastatic organ. Metastasis to the lungs can cause coughing, hemoptysis, chest pain, dyspnea, etc. Metastasis to the liver can cause liver pain, jaundice, ascites, abnormal liver function, etc. Metastasis to the bones can cause bone pain, pathological fractures, spinal cord compression, etc. Metastasis to the brain can cause headaches, dizziness, vomiting, visual impairment, hemiplegia (Figure 1B).

Metastasis pathways of cervical cancer. A: Distribution of metastatic modes: Direct spread is the predominant pathway, followed by lymphatic and hematogenous metastasis. B: Stepwise progression of metastasis: The diagram illustrates the invasion depth and spread from Stage I (local confinement) to Stage IV, where cancer cells disseminate to distant organs via lymphatic and vascular systems.

Among, lymphatic metastasis and hematogenous metastasis are both types of distal metastasis. Distal metastasis refers to the spread of cancer cells to organs or tissues far away from the primary tumor site through blood or lymphatic metastasis (19), such as the lungs, liver, bones, and brain, through hematogenous metastasis or lymphatic metastasis. These organs and tissues are essential for maintaining the normal physiological functions of the human body. Once invaded by cancer cells, they will seriously affect the patient's quality of life and health. Compared with local metastasis, distant metastasis is more difficult to treat and the patient's prognosis is worse (20). Because the cancer cells have spread to many parts of the body, it is difficult to completely remove them through surgery (21). Usually, comprehensive treatment methods such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and targeted therapy are required, but the effects of these treatments are often limited, and the 5-year survival rate of patients is low.

Types of Gene Mutations Associated with Distant Metastasis of Cervical Cancer

PDGFRA gene mutations are associated with the distal metastasis of cervical cancer

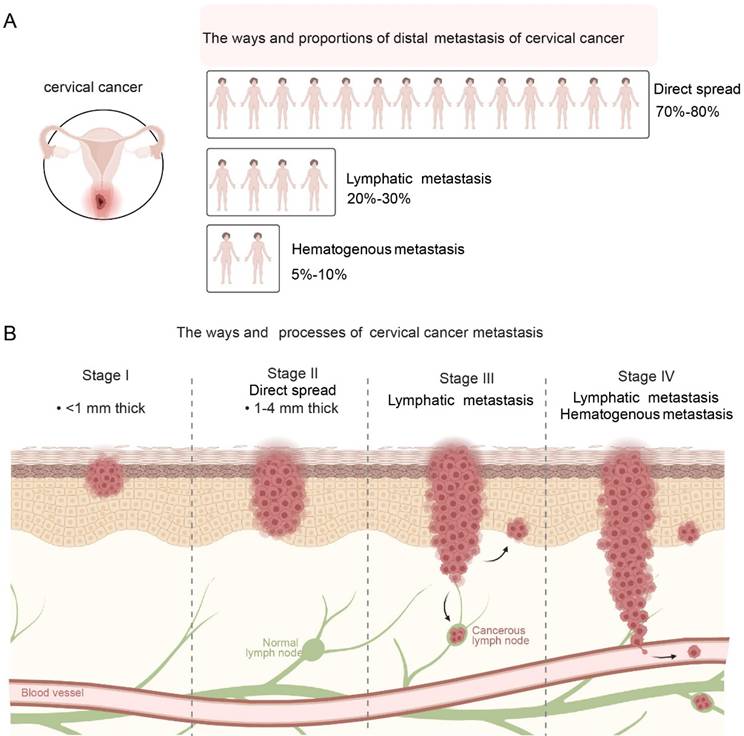

The PDGFRA gene is located on human chromosome 4q21.3 and contains 23 exons (22). Encodes platelet-derived growth factor receptor α (PDGFRα), a member of the tyrosine kinase receptor family (23). PDGFRα is mainly expressed in tumor cells and is involved in cell proliferation, migration, and angiogenesis (24). When the PDGFRA gene binds to the corresponding ligand platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), it activates the phosphorylation pathways of phosphatidylinositol, cAMP and various proteins, thereby regulating cell division and proliferation (23). Under normal physiological conditions, the expression and function of the PDGFRA gene are strictly regulated to maintain normal cell growth and differentiation. During tumorigenesis, abnormal activation of the PDGFRA gene can lead to tumorigenesis and promote tumor angiogenesis (25).

There are various types of PDGFRA gene mutations, including point mutations, insertion/deletion mutations, and gene amplification (26). Point mutations are the most common type of mutation, accounting for more than 50% of PDGFRA gene mutations (27). Point mutations can cause the amino acids encoded by genes to be replaced, thus affecting the structure and function of proteins (28). In gastrointestinal stromal tumors, common PDGFRA point mutation sites include D842V mutation in exon 18 (29). These mutations lead to enhanced tyrosine kinase activity of PDGFRα protein, which enables it to continuously activate downstream signaling pathways in the absence of ligand binding, promoting tumor cell proliferation and survival (30). Insertion/deletion mutations can lead to changes in gene structure, thereby affecting gene expression and function (31). In some tumors, insertion/deletion mutations in the PDGFRA gene can change the structure of the PDGFRα protein, making it unable to bind to ligands or activate downstream signaling pathways normally, thereby affecting the biological behavior of tumor cells (32). Gene amplification may lead to increased gene expression levels. Studies have found that the amplification of the PDGFRA gene is associated with the occurrence and development of cervical cancer (33). Gene amplification may lead to increased expression of PDGFRA protein, thereby affecting the growth and proliferation of cervical cancer cells (34).

In cervical cancer, although the incidence of PDGFRA gene mutation is relatively low, about 5%-10%, it is associated with the development and prognosis of cervical cancer (35). These mutations are mainly concentrated in the specific exon 18 region (36). Studies have shown that PDGFRA gene mutations are associated with the risk of cervical cancer metastasis (35). Cervical cancer patients with PDGFRA gene mutations are more likely to develop lymph node metastasis and distant metastasis. Its mechanism of action mainly includes the following aspects: In terms of cell proliferation, PDGFRA gene mutations can lead to abnormal activation of receptor signaling pathways (24), Continuously activate the downstream mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway and phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT signaling pathway, etc., to promote the proliferation and survival of tumor cells (37). In terms of cell migration and invasion, the mutated PDGFRα protein affects the interaction between tumor cells and the matrix (24), activates signaling molecules involved in cell motility and invasion, such as Rho GTPases and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) (38), This promotes the invasion and metastasis of tumor cells. PDGFRA gene mutations may also affect the response of tumor cells to treatment, resulting in reduced sensitivity of tumor cells to certain chemotherapy drugs or targeted therapy drugs, thereby affecting prognosis assessment and treatment selection (39). Studies have shown that cervical cancer patients with PDGFRA gene mutations have increased resistance to chemotherapy drugs such as cisplatin and poor treatment effects (40).

TP53 - related mutations are associated with the distal metastasis of cervical cancer

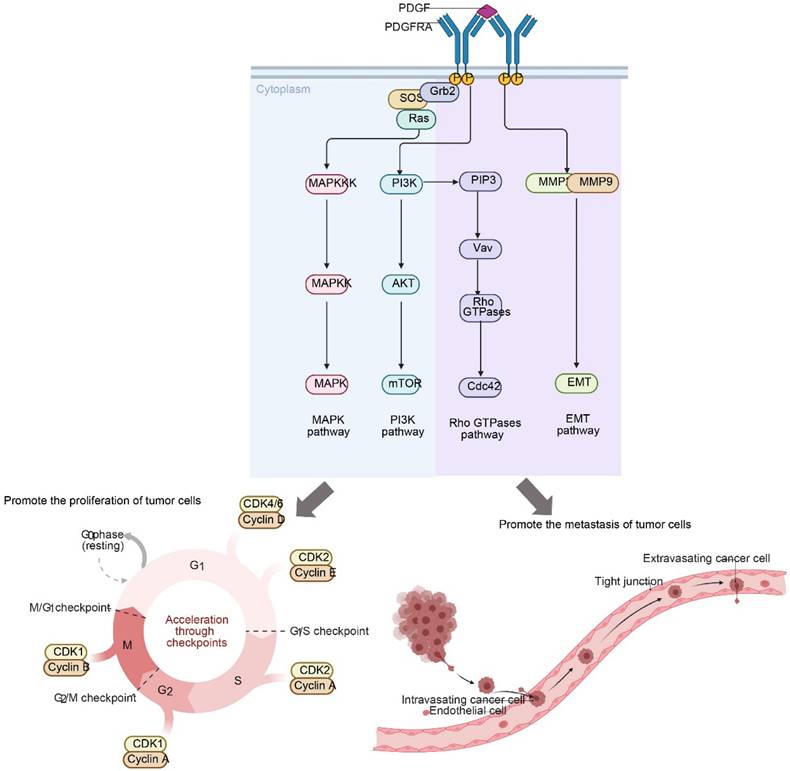

The TP53 gene is located on human chromosome 17p13.1, is approximately 20 kb in length, and contains 11 exons (41). It encodes a 53kDa nuclear phosphoprotein p53, which is an important tumor suppressor gene. (42). Under normal physiological conditions, p53 protein plays a variety of key biological functions in cells and plays a vital role in maintaining normal cell growth, differentiation and genome stability.

In cervical cancer, TP53 gene mutation is common, and about 30%-50% of cervical cancer patients have TP53 gene mutation (43). There are various types of TP53 gene mutations, including point mutations, deletions, insertions (44). Point mutations are the most common type of mutation, accounting for more than 80% of TP53 gene mutations. Point mutations usually occur in the highly conserved exon regions 5-8 of the TP53 gene (45). These regions encode amino acids that are essential for the structure and function of the p53 protein. Different types of TP53 gene mutations can lead to changes in the structure and function of p53 protein, thereby affecting its regulatory effects on cell cycle regulation, DNA repair, and cell apoptosis, thereby promoting the occurrence and development of cervical cancer (46).

TP53 gene mutations can lead to loss of function or abnormality of p53 protein, making it unable to properly regulate the cell cycle (47). Mutant p53 protein cannot effectively activate the expression of the p21 gene, resulting in dysfunctional cell cycle checkpoints (48). The cells cannot stop proliferating in time to repair damaged DNA, allowing the cells to continue to enter the cell cycle for division, increasing the risk of gene mutation and chromosomal instability, thereby promoting the proliferation of tumor cells. Studies have shown that in cervical cancer cells carrying TP53 gene mutations, the expression level of the p21 gene is significantly reduced, the cell cycle process is accelerated, and the cell proliferation ability is significantly enhanced (49).

TP53 gene mutations also affect the cell's DNA repair ability. Mutated p53 proteins cannot normally participate in the DNA repair process, resulting in a decrease in the cell's ability to repair DNA damage (50). This makes it impossible for damaged DNA to be repaired in time, further accumulating gene mutations and promoting the occurrence and development of tumors. Studies have found that in cervical cancer tissues with TP53 gene mutations, the expression and activity of DNA damage repair-related proteins are significantly reduced, the efficiency of DNA damage repair is reduced, and genomic instability is increased (51).

Mutations in PDGFRA promote the proliferation and metastasis of tumors. Upon ligand binding, PDGFRA activates key downstream signaling cascades, including the MAPK, PI3K-AKT-mTOR, Rho GTPases, and EMT pathways. These events collectively drive cell cycle acceleration (G1-S/M progression) and facilitate the metastatic process (intravasation and extravasation) by promoting cytoskeleton rearrangement and invasiveness.

In terms of cell apoptosis, TP53 gene mutations can cause p53 protein to lose its ability to induce cell apoptosis, leading to cell escape from apoptosis, thus allowing tumor cells to continue to survive and proliferate (52). The mutant p53 protein cannot effectively regulate the expression of pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic genes, which makes the apoptotic signaling pathway in the cell unable to be activated normally and reduces the sensitivity of the cell to apoptosis (53). Studies have shown that in cervical cancer cells with TP53 gene mutations, the expression levels of pro-apoptotic genes such as Bax are reduced, the expression levels of anti-apoptotic genes such as Bcl-2 are increased, cell apoptosis is inhibited, and the survival and proliferation abilities of tumor cells are enhanced (54).

TP53 gene mutation is also closely related to distant metastasis of cervical cancer. Mutant p53 protein not only loses its inhibitory effect on tumor cells, but also may acquire some new cancer-promoting functions that promote the invasion and metastasis of tumor cells (55). Studies show that cervical cancer patients with TP53 gene mutations are more likely to have distant metastasis and have a poor prognosis (56). Its mechanism of action may include: mutant p53 protein can enhance the invasion and metastasis ability of tumor cells by regulating some genes and signaling pathways related to tumor cell invasion and metastasis, such as matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) related genes. MMPs are a class of proteases that can degrade the extracellular matrix and play an important role in the invasion and metastasis of tumor cells (57). Mutant p53 protein can upregulate the expression of MMPs, promote the degradation of extracellular matrix, and provide conditions for the migration and invasion of tumor cells (58). EMT refers to the process in which epithelial cells lose polarity and intercellular connections and acquire mesenchymal cell characteristics, which can enable tumor cells to acquire stronger migration and invasion capabilities (59). Mutant p53 protein can induce EMT by regulating the expression of EMT-related genes E-cadherin, N-cadherin, and Vimentin, thereby promoting the invasion and metastasis of tumor cells (60).

Mutant p53 regulates EMT primarily through three pathways: direct regulation, signaling pathway interaction, and epigenetic modification. Firstly, it can directly bind to the promoters of EMT-promoting factors such as SNAI1 and TWIST1, enhancing their activity, or weaken the effects of EMT-repressing factors such as ZEB1 by competitive binding sites, thereby regulating the expression of epithelial and stromal markers (61). Secondly, it can interact with signaling pathways such as PI3K/Akt, TGF-β/Smad, and Wnt/β-catenin, for example, binding to the PI3K catalytic subunit to enhance its activity and stabilize Snail, or enhancing TGF-β-mediated Smad phosphorylation, indirectly promoting the EMT process (62). Thirdly, it can also recruit histone-modifying enzymes such as HDACs and EZH2, or upregulate DNMTs activity, epigenetically modifying EMT-related genes such as E-cadherin, inhibiting epithelial marker gene transcription or silencing EMT-repressing genes, ultimately achieving EMT regulation (63).

PIK3CA - related mutations are associated with the distal metastasis of cervical cancer

The PIK3CA gene is a key proto-oncogene located on chromosome 3 and has 20 exons (64). This gene belongs to the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway and is primarily responsible for encoding the p110α protein, a catalytic subunit of the PI3K enzyme (65). During normal cell signaling, the PI3K enzyme is activated by cell surface receptors (66). By phosphorylating other proteins, it triggers a series of intracellular signal transduction, thereby regulating various biological processes such as cell growth, proliferation, survival, and metabolism (67).

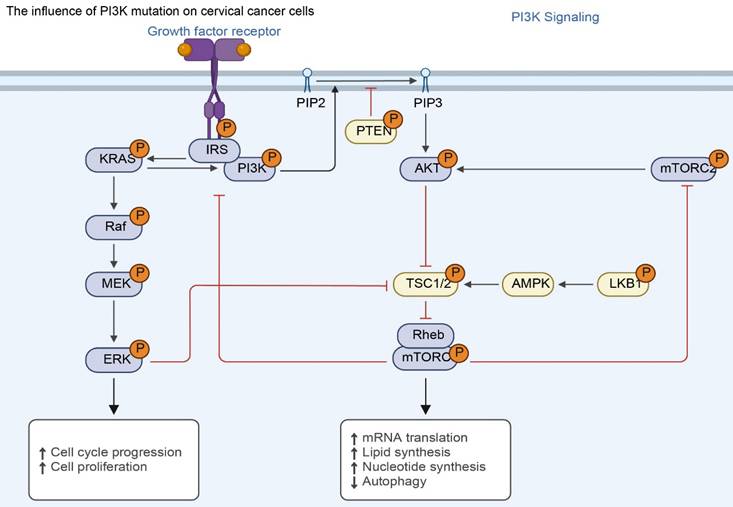

PIK3CA gene mutations can lead to abnormalities in the structure and function of the p110α protein, causing the PI3K enzyme to be in a state of continuous activation, thereby enhancing the conduction of intracellular signals and causing disorders in the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway (68). Abnormal activation of this pathway will cause abnormal cell proliferation, resistance to apoptosis, promotion of angiogenesis, and enhancement of cell migration and invasion, ultimately leading to the occurrence and development of tumors (69). About 80% of PIK3CA mutations occur in two hotspots: the helical region and the kinase region (70). The three most common mutations are H1047R in exon 20, E542K and E545K in exon 9 (71).

In cervical cancer, PIK3CA gene mutation also has a certain incidence rate, about 10%-20% (72). Studies have shown that PIK3CA gene mutations are closely related to distant metastasis of cervical cancer. A study of 100 patients with cervical cancer found that the frequency of PIK3CA gene mutations in patients with distant metastasis was significantly higher than that in patients without metastasis, at 30% and 10% respectively (73). This suggests that PIK3CA gene mutation may be an important risk factor for distant metastasis of cervical cancer (74).

Impact of TP53 Mutations on Tumor Suppression Mechanisms. Under normal conditions, activated P53 triggers cell cycle arrest, DNA repair, or apoptosis in response to damage. TP53 mutations impair these tumor-suppressive functions, leading to the failure of checkpoints (ATM/ATR-CHK1/2 axis) and promoting the unchecked proliferation and malignant progression of cervical cancer cells.

PIK3CA gene mutation activates the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway, which significantly affects the proliferation, survival, and migration of cervical cancer cells (75). In terms of cell proliferation, activated Akt protein can phosphorylate a variety of downstream substrates (76), such as mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), which promotes protein synthesis and cell cycle progression, thereby accelerating the proliferation of cervical cancer cells. The study found that in cervical cancer cell lines carrying PIK3CA gene mutations, cell proliferation was significantly accelerated, and the expression of proliferation-related proteins such as cyclin D1 was significantly upregulated (77). In terms of cell survival, Akt protein can inhibit the activity of apoptosis-related proteins Bad and Caspase, thereby enhancing the survival ability of cervical cancer cells (78). The experiment showed that when the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway was inhibited, the apoptosis rate of cervical cancer cells carrying the PIK3CA gene mutation increased significantly, indicating that the activation of this signaling pathway plays an important protective role in cell survival (79). In terms of cell migration and invasion, activation of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway can regulate cytoskeletal reorganization (80), Promote the expression and secretion of proteins such as matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), thereby enhancing the migration and invasion ability of cervical cancer cells. Studies have shown that in cervical cancer cells with PIK3CA gene mutations, the expression levels of proteins such as MMP-2 and MMP-9 are significantly increased, and the migration and invasion abilities of cells are significantly enhanced (81).

BRAF and EGFR gene mutations

In addition to the genes mentioned above, mutations in the BRAF and EGFR genes also play a significant role in distant metastasis in cervical cancer. The BRAF gene, a key molecule in the MAPK signaling pathway, has a hotspot mutation, V600E, which occurs in approximately 3%-5% of cervical cancers (82). This mutation leads to sustained activation of the BRAF protein, which in turn activates the downstream MEK/ERK signaling pathway through a phosphorylation cascade, leading to upregulation of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT)-related transcription factors such as Snail and Twist, ultimately enhancing tumor cell migration and invasion (83). Clinical studies have shown that cervical cancer patients with the BRAF V600E mutation are more likely to develop lung metastases and have a relatively poor prognosis (84).

The effect of PI3K mutations on cervical cancer cells. Mutations in PIK3CA or loss of PTEN inhibition lead to constitutive activation of the PI3K-AKT-mTOR axis. This sustained signaling promotes malignant phenotypes—including uncontrolled cell cycle progression, protein/lipid synthesis, and inhibition of autophagy—independent of growth factor stimulation.

EGFR (epidermal growth factor receptor) gene mutations are also closely associated with the metastatic potential of cervical cancer, with mutations such as L858R being particularly common (85). Mutated EGFR can activate the downstream dual signaling pathways of PI3K/Akt and MAPK through autophosphorylation (86). Activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway enhances cell survival and promotes the secretion of matrix metalloproteinases (such as MMP-2 and MMP-9) (87). Sustained activation of the MAPK pathway further accelerates cell cycle progression and EMT, collectively enhancing tumor cell migration. In vitro studies have demonstrated that targeted inhibitors targeting EGFR mutations (such as gefitinib) can specifically block these signaling pathways and significantly inhibit the invasive ability of cervical cancer cells carrying these mutations, providing a potential target for the treatment of these patients (88).

HPV integration-related gene mutations

Human papillomavirus (HPV) integration into the host genome is a key driver of cervical cancer development. HPV16 integration is particularly common, withHPV integration-related genetic abnormalities have been detected in approximately more than 50% of patients with cervical squamous cell carcinoma (89). The E7 oncoprotein in the HPV genome is a core molecule mediating malignant transformation (90). It directly binds to the retinoblastoma protein (RB1), leading to RB1 functional inactivation (91). This process not only relieves RB1's inhibitory effect on the cell cycle, leading to abnormal cell proliferation, but also indirectly induces the degradation of the tumor suppressor gene TP53, impairing the cell's DNA damage repair capacity and apoptosis mechanism.

Notably, genetic abnormalities triggered by HPV integration often synergize with mutations in other driver genes. For example, when HPV16 E7-mediated RB1 inactivation coexists with PIK3CA mutations, it can significantly accelerate tumor cell invasion and metastasis through the dual mechanisms of “cell cycle deregulation - accelerated proliferation” and “PI3K/Akt pathway activation - enhanced migration (92).” This synergistic effect of multiple gene abnormalities is not only a key factor in the increased malignancy of cervical cancer but also provides a molecular rationale for the development of combined targeted therapy strategies in clinical practice.

Other related gene mutations

In addition to the above-mentioned gene mutations, some gene mutations such as KRAS and PTEN are also associated with distant metastasis of cervical cancer, and they play a potential role in the metastasis of cervical cancer.

The KRAS gene is an important member of the RAS gene family, encoding a small GTPase that plays a key molecular switch role in cell signaling pathways (93). Normally, KRAS protein is inactive when bound to GDP (94). When stimulated by upstream signals, KRAS protein binds to GTP and becomes activated. The activated KRAS protein can activate downstream mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways, phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase (PI3K)/AKT signaling pathways (95), regulates biological processes such as cell proliferation, differentiation, survival and migration (96). KRAS gene mutations are common in many tumors, which can reduce the GTPase activity of KRAS protein, causing it to remain in an activated state and continuously activate downstream signaling pathways, thereby promoting the occurrence and development of tumors (97). In cervical cancer, although the incidence of KRAS gene mutation is relatively low, about 5%-10%, studies have shown that this gene mutation is associated with distant metastasis of cervical cancer (98). A study of 150 patients with cervical cancer found that the frequency of KRAS gene mutations was significantly higher in patients with distant metastasis than in those without metastasis, at 15% and 5%, respectively (99). Further mechanistic studies have shown that KRAS gene mutations promote the proliferation, migration and invasion of cervical cancer cells by activating the MAPK and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways, thereby increasing the risk of distant metastasis of cervical cancer (100). In cervical cancer cell lines carrying KRAS gene mutations, cell proliferation was significantly accelerated, and migration and invasion abilities were significantly enhanced. At the same time, the phosphorylation levels of key proteins in downstream signaling pathways, such as ERK and AKT, were significantly increased (101).

Clinically, the detection of KRAS mutations has practical guiding value for the diagnosis and treatment of cervical cancer: for patients with locally advanced cervical cancer (LACC), if a KRAS mutation is detected preoperatively, the risk of distant metastasis should be considered, and the frequency of postoperative imaging follow-up should be increased (102); while in the treatment of metastatic cervical cancer, KRAS mutations may indicate that the patient's sensitivity to platinum-based chemotherapy (such as cisplatin) is reduced—because the continuously activated PI3K/AKT pathway enhances the ability to repair DNA damage, leading to chemotherapy resistance(103). Such patients may need to prioritize combination therapy (such as PI3K inhibitors) to improve treatment response.

The PTEN gene is an important tumor suppressor gene. The PTEN protein it encodes has phosphatase activity and can negatively regulate the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. In normal cells, PTEN protein inhibits the activation of the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway by dephosphorylating phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-triphosphate (PIP3) to phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2), thereby inhibiting cell proliferation, promoting cell apoptosis, and inhibiting cell migration and invasion (104). When the PTEN gene is mutated or missing, the expression or activity of PTEN protein decreases, and it cannot effectively inhibit the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, resulting in the continued activation of the signaling pathway, which in turn promotes the occurrence and development of tumors (105). In cervical cancer, the mutation or deletion of PTEN gene also has a certain incidence rate, about 10%-20%. Studies have found that abnormalities in PTEN gene are closely related to distant metastasis of cervical cancer (8). A study analyzed 120 patients with cervical cancer and found that the frequency of PTEN gene mutation or deletion was significantly higher in patients with distant metastasis than in patients without metastasis, at 25% and 10%, respectively (106). PTEN gene abnormalities lead to overactivation of the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, which may promote the degradation of the extracellular matrix and enhance the migration and invasion ability of cervical cancer cells by upregulating the expression of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), thereby promoting the distant metastasis of cervical cancer. In cervical cancer cells with PTEN gene deletion, the expression levels of proteins such as MMP-2 and MMP-9 are significantly increased, and the migration and invasion ability of cells are significantly enhanced. At the same time, the phosphorylation level of AKT, a key protein in the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, is also significantly increased (107).

Application of Gene Mutation Detection in the Diagnosis of Distant Metastasis of Cervical Cancer

Detection of gene mutations associated with distant metastasis of cervical cancer is of great significance for early detection of potential metastasis risk, improving diagnostic accuracy and specificity, and providing important basis for clinical treatment decision-making.

Early detection of potential metastasis risks

Gene mutations often appear before distant metastasis of cervical cancer (108). By detecting these gene mutations, patients with a high risk of distant metastasis can be identified in advance. Studies have shown that cervical cancer patients with PIK3CA gene mutations have a significantly increased risk of distant metastasis (73). A prospective study of 200 patients with cervical cancer found that during follow-up, 30% of patients with positive PIK3CA gene mutations developed distant metastasis within 2 years, while only 10% of patients with negative PIK3CA gene mutations developed distant metastasis. This suggests that by detecting PIK3CA gene mutations, patients with a high risk of distant metastasis can be identified early, providing an important time window for clinical intervention (109). Early detection of potential metastasis risks can enable patients to receive more aggressive treatments in a timely manner, such as intensive chemotherapy, radiotherapy or targeted therapy, which may delay or prevent the occurrence of distant metastasis and improve the patient's survival rate (110).

Improving the accuracy and specificity of diagnosis of distant metastasis

Detection of gene mutations can improve the accuracy and specificity of diagnosis of distant metastasis of cervical cancer (111). Traditional imaging examinations and tumor marker detection diagnostic methods have certain limitations (112). Imaging examinations may be difficult to detect tiny metastases and may easily lead to missed diagnosis (113); Tumor marker testing has poor specificity and may be elevated in some benign diseases, leading to false positive results (114). Gene mutation detection has high specificity and can accurately reflect the molecular characteristics of tumor cells, providing a more reliable basis for diagnosis. For some early metastatic lesions that are difficult to diagnose through imaging examinations, combining gene mutation detection results can improve the accuracy of diagnosis. (115). The study showed that when diagnosing patients with suspected cervical cancer lung metastasis, the accuracy of diagnosis increased from 70% to 85% by testing TP53 gene mutations and lung imaging findings simultaneously (116). This suggests that combining gene mutation detection with traditional diagnostic methods can make up for the shortcomings of traditional methods and improve the accuracy and specificity of diagnosis.

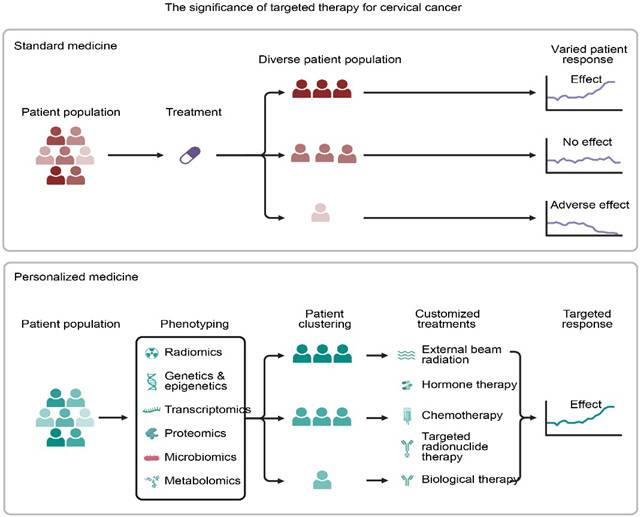

Provision of bases for clinical treatment decisions

The results of gene mutation detection provide an important basis for clinical treatment decisions. Different types of gene mutations have different effects on the biological behavior and treatment response of cervical cancer. Understanding the patient's gene mutation status can help doctors develop personalized treatment plans and improve the targetedness and effectiveness of treatment. For breast cancer patients with HER2 gene amplification, HER2-targeted therapeutic drugs are used clinically (117). These drugs can specifically bind to HER2 protein and block its signal transduction, thereby inhibiting the growth and metastasis of tumor cells and significantly improving the survival rate and quality of life of patients (118). In cervical cancer, for patients with PIK3CA gene mutations, since PIK3CA gene mutations activate the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway, making tumor cells more sensitive to PI3K/Akt signaling pathway inhibitors, targeted therapy with PI3K/Akt signaling pathway inhibitors can be considered (119). Studies have shown that in cervical cancer patients with PIK3CA gene mutations, the objective response rate of patients treated with PI3K/Akt signaling pathway inhibitors was significantly higher than that of patients who did not use the inhibitors. This shows that choosing the appropriate treatment method based on the results of gene mutation detection can improve the treatment effect and the prognosis of patients (120).

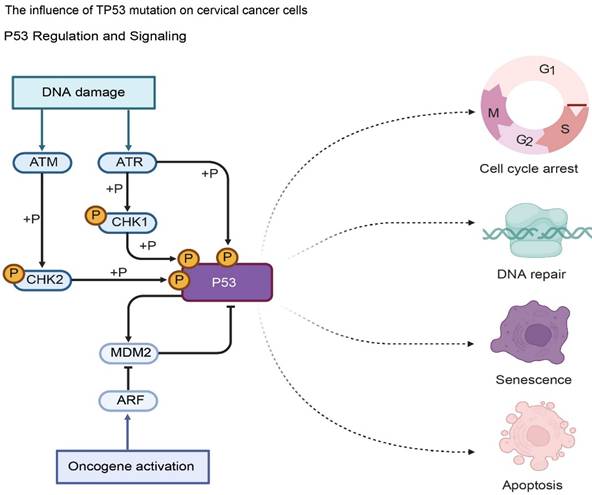

Gene therapy for cervical cancer

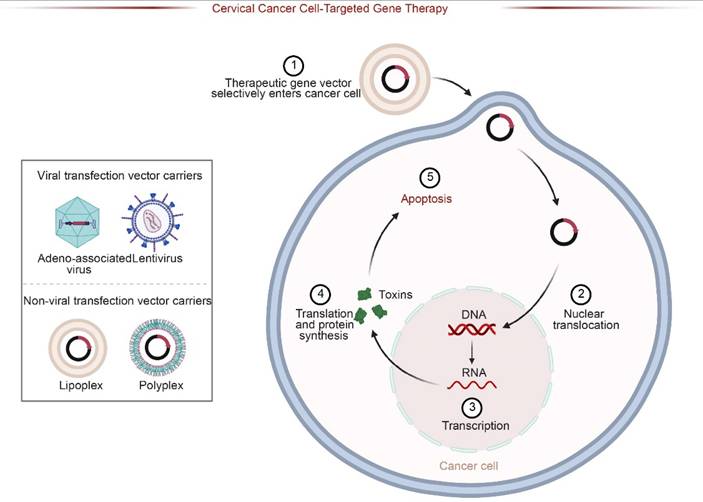

The occurrence of cervical cancer is related to multiple gene abnormalities, including activation of oncogenes and inactivation of tumor suppressor genes (121). Gene therapy aims to correct these gene abnormalities through various means, restore the normal function of cells, and thus inhibit the growth and spread of tumor cells (122).

Gene therapy: Gene replacement: Introducing normal tumor suppressor genes into tumor cells to supplement or replace missing or inactivated tumor suppressor genes and restore their function of inhibiting tumor growth. The p53 gene is an important tumor suppressor gene. In many cervical cancer patients, the p53 gene is mutated or missing (123). By introducing the normal p53 gene into tumor cells, it can induce tumor cell apoptosis and inhibit tumor growth. Gene silencing: Technologies such as RNA interference (RNAi) are used to specifically inhibit the expression of oncogenes (124). For the oncogenes overexpressed in cervical cancer, the E6 and E7 genes of human papillomavirus (HPV), corresponding RNAi molecules were designed. These molecules can effectively reduce the expression levels of these genes, thereby inhibiting the proliferation and survival of tumor cells. Immunogeneous gene therapy: By introducing immune regulatory genes, the body's immune response to tumor cells is enhanced (125). For example, genes encoding cytokines (such as interleukin-2, interferon, etc.) are introduced into tumor cells or immune cells. This can promote the activation and proliferation of immune cells and enhance their killing effect on tumor cells (126).

Therapeutic Strategies for Distant Metastasis of Cervical Cancer Based on Gene Mutations

Targeted therapy is a treatment method that intervenes in specific molecular targets of tumor cells. It has the advantages of precision, high efficiency and few side effects (127). In the treatment of distant metastasis of cervical cancer, targeted therapy mainly targets gene mutations of PDGFRA and PIK3CA, which are closely related to distant metastasis of cervical cancer (128). By inhibiting the proteins encoded by these mutant genes or their related signaling pathways, the growth, proliferation, invasion and metastasis of tumor cells can be inhibited.

Targeted Therapy for PDGFRA Gene Mutations

Targeted therapy for PDGFRA gene mutations focuses on blocking the PDGFRA-mediated signaling pathway through tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) to inhibit tumor cell proliferation and metastasis. Imatinib, as a first-generation TKI, can competitively bind to the ATP binding site of PDGFRA, inhibiting its tyrosine kinase activity, thereby blocking the activation of downstream MAPK and PI3K/AKT pathways (129). In clinical studies of advanced or metastatic cervical cancer, the objective response rate (ORR) of imatinib monotherapy in patients with PDGFRA mutations reached 22%-28%, with some patients experiencing tumor volume reduction of more than 30% and significant relief of bone metastasis-related pain symptoms (130). Furthermore, the multi-target TKI sunitinib, by simultaneously inhibiting PDGFRA and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR), exhibits a synergistic effect in patients with PDGFRA mutations and highly vascularized metastases (such as liver metastases)—not only inhibiting tumor cell activity through PDGFRA, but also blocking tumor angiogenesis and reducing nutrient supply, resulting in a disease control rate (DCR) that is 15%-20% higher than that of imatinib (131).

Schematic of Targeted Gene Therapy Strategies. Therapeutic genes are delivered via viral (e.g., Adeno-associated virus) or non-viral vectors (e.g., Lipoplexes). The vectors selectively enter cancer cells, undergo nuclear translocation, and express therapeutic proteins (e.g., toxins), ultimately inducing apoptosis in target cervical cancer cells.

However, the clinical benefits of PDGFRA-targeted therapy are often limited by the emergence of drug resistance, and different resistance mechanisms are closely related to treatment regimens. Secondary mutations are the main cause of imatinib resistance, with the PDGFRA exon 18 D842V mutation being the most typical—this mutation reduces the affinity of imatinib for the receptor by altering the ATP-binding pocket structure of PDGFRα, resulting in the drug's inability to effectively inhibit kinase activity (29).Clinical data show that among PDGFRA-mutant cervical cancer patients treated with imatinib, approximately 35%-40% were found to have the D842V mutation 6-12 months after treatment (132). The progression-free survival (PFS) of these patients was more than 50% shorter than that of those without the mutation, and the response rate to subsequent treatment was significantly lower (37). In addition, PDGFRA gene amplification may also lead to drug resistance. Some patients have an increased PDGFRA copy number after long-term treatment, which leads to overexpression of PDGFRA protein. Even in the presence of drugs, the pathway can still be activated. The incidence of this type of drug resistance in the sunitinib treatment population is approximately 15%-20% (26). In response to the aforementioned drug resistance, next-generation TKIs such as avatinib have higher inhibitory activity against D842V mutations. In vitro experiments show that its inhibitory efficiency against D842V mutant PDGFRA is more than 20 times that of imatinib. Its efficacy has been confirmed in gastrointestinal stromal tumors and it is expected to become a salvage treatment option for cervical cancer patients with PDGFRA D842V mutations (29).

Targeted therapy for PIK3CA gene mutations

Targeted therapy for PIK3CA gene mutations is based on PI3K inhibitors. By inhibiting the activity of PI3Kα catalytic subunits, it blocks the abnormal activation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway (133). Alpelisib, as a selective inhibitor of PI3Kα, can specifically bind to mutant PI3Kα and has a weak inhibitory effect on wild-type PI3K (134). Therefore, the incidence of toxic side effects (such as hyperglycemia and rash) is reduced by 20%-25% compared with pan-PI3K inhibitors (135). In clinical trials of PIK3CA-mutated metastatic cervical cancer, apelelis monotherapy achieved an ORR of 18%-22% and a median PFS of 5.6-6.2 months. Furthermore, in patients with lung metastases complicated by PI3K/AKT pathway overactivation, its lesion shrinkage rate was significantly higher than that of chemotherapy (136). The pan-PI3K inhibitor BKM120, which inhibits four PI3K subtypes (α, β, γ, and δ), showed advantages in patients with PIK3CA mutations and other PI3K subtype abnormalities (such as PI3Kβ activation). In vitro experiments showed that it inhibited cervical cancer cell proliferation by 60%-65% and induced 30%-35% apoptosis (137).

The resistance mechanisms to PI3K inhibitors are more complex, with bypass signaling activation and pathway remodeling being the main types. KRAS activation is a common bypass pathway in apelelis resistance (138). When the PI3K pathway is inhibited, some patients develop KRAS gene mutations (such as G12D and G13V) or KRAS protein overexpression, which compensates by activating the downstream MAPK pathway (ERK phosphorylation level increases 2-3 times) to maintain tumor cell activity (139). Clinical studies have shown that KRAS activation was detected in about 25%-30% of patients who failed apelelis treatment (140). After these patients received combination therapy with MEK inhibitors (such as trametinib), the ORR could recover to 15%-18% and the PFS could be prolonged to 4.0-4.5 months (141). In addition, PTEN loss can also lead to resistance to PI3K inhibitors: PTEN is a negative regulator of the PI3K/AKT pathway. Its gene deletion or protein expression downregulation leads to reduced PIP3 degradation. Even if PI3K is inhibited, AKT phosphorylation can still be maintained (p-AKT level increases by 1.8-2.2 times) (142). In patients treated with BKM120, the incidence of drug resistance in those with PTEN loss is 40%-45% higher than that in those with normal PTEN, and the time of drug resistance onset is 2-3 months earlier. For these patients, the combination of PTEN activators (such as disulfiram) can reduce AKT activity by 50%-55% and partially restore the sensitivity of tumor cells to PI3K inhibitors (143).

Conclusion

This review systematically elucidates the regulatory mechanisms of gene mutations in the occurrence, development, and distant metastasis of cervical cancer. Through multidimensional analysis, it clarifies the action pathways of core mutated genes: genes such as PDGFRA, TP53, and PIK3CA collectively promote cervical cancer metastasis through mechanisms such as aberrant activation of signaling pathways (e.g., PI3K/Akt, MAPK), induction of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), enhanced tumor angiogenesis, and remodeling of the tumor microenvironment. The high metastasis association of low-frequency PDGFRA mutations, the dual regulation of cell cycle and apoptosis by TP53 mutations, and the pathway activation effects of hotspot mutations in PIK3CA (e.g., exon9 E542K/E545K, exon20 H1047R) provide crucial clues for understanding the molecular mechanisms of metastasis.

In terms of clinical translational value, gene mutation detection overcomes the limitations of traditional imaging and tumor marker diagnosis. It can not only provide early warning of metastasis risk (e.g., the metastasis rate within 2 years for PIK3CA-mutated patients reaches 30%, significantly higher than the 10% for wild-type patients), but also guide personalized treatment. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors targeting PDGFRA (such as imatinib and sunitinib) and PI3K inhibitors targeting PIK3CA (such as apelips and BKM120) have shown preliminary efficacy, but resistance mechanisms (such as pathway compensatory activation and enhanced drug efflux pumps) and cost issues still need to be addressed. Furthermore, the synergistic effect of HPV integration and driver gene mutations (e.g., co-mutation of HPV16 E7 and PIK3CA accelerates metastasis), and the metastasis-regulating role of rare mutations such as BRAF (V600E) and EGFR (L858R) provide new directions for expanding therapeutic targets.

Future research should focus on the framework of "mutation-spatiotemporal-microenvironment-clinical intervention," and promote the application of "mutation-driven precision metastasis prevention" from theory to clinical practice by constructing AI metastasis risk prediction models through multi-center cohorts, developing ctDNA dynamic monitoring technology, and optimizing combination therapy regimens (such as PI3Kα inhibitors combined with PD-1 antibodies), ultimately improving the long-term survival rate and quality of life of patients with advanced cervical cancer.

Discussion

This study provides theoretical and practical references for research on the association between cervical cancer gene mutations and distant metastasis. However, key analyses are needed from three aspects: mechanistic depth, technological limitations, and treatment challenges, to improve scientific rigor and clarify future directions.

Paradigm Shift from Standard to Personalized Medicine. Standard treatment often results in variable patient outcomesdue to heterogeneity. In contrast, personalized medicine utilizes multi-omics phenotyping** (genetics, radiomics) to stratify patients, enabling customized therapeutic strategies that enhance treatment consistency and efficacy.

Core mutation gene mechanisms

From "Association" to "Causality" Current research confirms that PDGFRA, TP53, and PIK3CA mutations are associated with metastasis, but mechanistic gaps remain: the molecular interaction patterns of PDGFRA with low frequency (5%-10%) and high metastasis association (such as direct interaction with Rho GTPases and MMPs) and functional differences at different stages of metastasis are unclear, requiring verification of its "metastasis switch" role through CRISPR-edited PDX models combined with single-cell proteomics; the regulation of cell cycle and EMT by TP53 mutations does not differentiate between exon5-8 hotspot mutations, and the interaction and co-metastasis mechanism with HPV E6/E7 proteins need further analysis, requiring verification using technologies such as dual-luciferase reporter genes; the activation intensity of PIK3CA hotspot mutations (exon9 E542K/E545K, exon20 H1047R) is not correlated with drug sensitivity, requiring the establishment of a "mutant subtype - pathway activity - drug IC50" model. Database-guided medication.

Detection technology and clinical application: a breakthrough from "usable" to "reliable"

While gene mutation detection compensates for the shortcomings of traditional diagnosis, it has limitations: Conventional NGS has a detection rate of < 50% for low-abundance mutations in ctDNA (VAF < 1%). Ultrasensitive technologies such as ddPCR need to be introduced to establish a "VAF threshold - metastasis risk" relationship (e.g., verifying VAF≥0.5% as a PDGFRA warning threshold), and to construct a combined diagnostic panel of "gene mutation + epigenetic regulation" to increase diagnostic sensitivity from 85% to over 90%. Currently, the standards for "mutation abundance - clinical significance" are not uniform (e.g., differences in VAF interpretation for TP53 mutations). Guidelines need to be developed in collaboration with international institutions based on tens of thousands of samples to clarify the risk stratification of mutation types and co-mutations.

Treatment strategies

The Leap from "Effective" to "Long-Lasting" Targeted therapy faces resistance and cost issues: Resistance to PDGFRA and PIK3CA targeted drugs stems from secondary mutations (e.g., PDGFRA D842V), pathway compensation (e.g., MAPK activation), and microenvironmental influences (e.g., CAFs secreting IL-6). Dynamic ctDNA monitoring is needed to capture resistant clones, and specific inhibitors (e.g., MEK inhibitors combined with PI3K inhibitors) need to be developed. New combination therapies such as "targeted therapy + immunotherapy" (e.g., PI3K inhibitors reversing immunosuppression followed by PD-1 antibodies) are under-explored and require umbrella trials for validation. High treatment costs (e.g., apelelis at 15,000 RMB per month) limit widespread adoption, necessitating the development of low-cost multi-gene detection chips and the promotion of domestically produced targeted drugs for inclusion in medical insurance.

Future research directions: multi-dimensional integrated planning

The research should revolve around the framework of "mutation - spatiotemporal - microenvironment - intervention": Basic research should construct double/triple mutant cell lines and conditional knockout mouse models to analyze the positive feedback of "mutant cells - microenvironment" (e.g., PDGFRA mutant cells recruit MDSCs); Clinical translation should establish multi-center cohorts (e.g., NCT-CERV-PROSPECT) and develop AI-based metastasis risk prediction models (incorporating mutation, pathology, and microenvironment indicators); Technological innovation should create a "drug resistance early warning - dynamic drug administration" platform to monitor drug resistance signals and adjust dosage through single-cell multi-omics to prolong progression-free survival of targeted therapy.

Looking Forward

Over the next five years, cervical cancer metastasis research should be centered around a four-dimensional framework: "Mutation-Spatiotemporal-Microenvironment-Clinical Intervention":

Establish a multicenter prospective cohort (NCT-CERV-PROSPECT) covering three continents, integrating whole-exome, methylation, immune repertoire, and radiomics data to develop an AI-driven metastasis risk prediction model. The umbrella trial (UMBRELLA-CERVIX) was launched to evaluate the synergistic efficacy of a PI3Kα inhibitor combined with a PD-1 antibody in PIK3CA-mutant/immune-desert tumors, stratified by mutation subtype. Dynamic ctDNA response was prespecified as an early surrogate endpoint.

Using CRISPR biallelic gene editing and PDX-humanized mouse models, the researchers elucidated the mechanism by which TP53/PIK3CA co-mutations amplify PI3K signaling through the exosome-miR-21-PTEN axis, identifying druggable nodes.

Summary of key molecular events and clinical implications in cervical cancer metastasis

| Primary Category | Secondary Category | Core Content (Refined) |

|---|---|---|

| Metastatic Pathways | Direct Spread (70%-80%) | • Most common mode; invades vaginal wall, uterine cavity, and pelvic wall • Symptoms: Irregular bleeding, lumbosacral pain • Risk factors: Tumor size, location, and differentiation |

| Lymphatic Metastasis (20%-30%) | • Progression: Level I (pelvic) → Level II (para-aortic) nodes • Risk factors: Advanced stage, adenocarcinoma subtype, poor differentiation | |

| Hematogenous Metastasis (5%-10%) | • Sites: Lungs, liver, bones, brain • Prognosis: Rare but associated with poor outcomes | |

| Gene Mutations | PDGFRA | • Role: Activates MAPK/PI3K pathways; upregulates Rho GTPases/MMPs • Impact: Linked to lymph node metastasis; increases cisplatin resistance |

| TP53 | • Mechanism: Impairs cell cycle checkpoints (p21) and apoptosis (Bax/Bcl-2) • Effect: Promotes EMT and invasion; associated with 30-50% of cases | |

| PIK3CA | • Hotspots: Exon 9 & 20; constitutively activates Akt/mTOR • Clinical: Higher mutation rate in metastatic patients (30%) vs. non-metastatic (10%) | |

| Other (BRAF, EGFR, KRAS, PTEN) | • BRAF/KRAS: Activate MAPK pathway; BRAF V600E linked to lung metastasis • PTEN: Loss leads to uncontrolled PI3K signaling and MMP upregulation | |

| Clinical Application | Early Identification | • Prognostic Value: PIK3CA mutations predict a significantly higher 2-year metastasis rate (30% vs 10%) |

| Diagnosis & Treatment | • Accuracy: Gene detection combined with imaging improves specificity (e.g., distinguishing lung metastasis) • Targeted Therapy: Supports use of TKIs (Imatinib) or PI3K inhibitors (Alpelisib) for precise intervention |

Developing an international consensus standard for mutation abundance: Based on cross-validation using ddPCR and NGS, a VAF of 1% was established as a high-risk threshold, which will be incorporated into future FIGO staging updates.

Developing a "drug resistance early warning" platform: Leveraging single-cell multi-omics to monitor newly acquired mutations during treatment in real time, the researchers developed adaptive dosing algorithms to reduce the incidence of drug resistance and healthcare costs. Through the above-mentioned multi-dimensional closed-loop research, it is expected that by 2030, the leap from theory to clinic of "mutation-driven precise metastasis prevention" will be achieved, significantly improving the long-term survival and quality of life of patients with advanced cervical cancer.

Acknowledgements

The successful completion of this study would not have been possible without the support and assistance of all parties involved, for which we extend our sincere gratitude.

We thank the Shandong Provincial Medical and Health Science and Technology Projects (202309031407, 202401030359) for their funding support, which laid the foundation for this research.

We thank all members of the author team for their collaboration and contributions in research design, data analysis, and manuscript writing and revision.

Special thanks to Biorender software for its professional support in creating figures and tables; its convenient functions and visualization effects helped to clearly present complex molecular mechanisms and research logic.

We also thank Weifang People's Hospital for providing the research platform, and our experts and colleagues for their guidance and assistance.

Funding

We thank the Shandong Provincial Medical and Health Science and Technology Project (202309031407) for its support, the Shandong Provincial Medical and Health Science and Technology Project (202401030359).

Author contributions

Furong Hao and Niannian Li conceived the idea and designed the study. Yinghua Guo and Shilong Li collected and analyzed the data. Tingting Liu, Xiaolong Chang drafted the manuscript. Peiyan Qin critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. Nan Wang, Yingxiao Jiang and Na Lv contributed to the interpretation of the data and approved the final version of the manuscript for publication.

Competing Interests

The authors have declared that no competing interest exists.

References

1. Chen Y, Xie J, Xie B, Zhong H, Zhang Z, Lin Q. et al. Integrated proteomic and lipidomic analysis revealed potential plasma biomarkers for cervical cancer. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2026;267:117131

2. Effah K, Anthony R, Tekpor E, Amuah JE, Wormenor CM, Tay G. et al. HPV DNA Testing and Mobile Colposcopy for Cervical Precancer Screening in HIV Positive Women: A Comparison Between Two Settings in Ghana and Recommendation for Screening. Cancer Control. 2024;31:10732748241244678

3. Lin S, Gao K, Gu S, You L, Qian S, Tang M. et al. Worldwide trends in cervical cancer incidence and mortality, with predictions for the next 15 years. Cancer. 2021;127(21):4030-4039

4. Noguchi T, Zaitsu M, Oki I, Haruyama Y, Nishida K, Uchiyama K. et al. Recent Increasing Incidence of Early-Stage Cervical Cancers of the Squamous Cell Carcinoma Subtype among Young Women. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(20):7401

5. Li H, Wu X, Cheng X. Advances in diagnosis and treatment of metastatic cervical cancer. J Gynecol Oncol. 2016;27(4):e43

6. Hernandez C, Glidden A, Sandhu M, Agrawal K, Caicedo Murillo M, Heritage C. et al. A Rare Case of Aggressive Atypical Cervical Cancer With Multi-Organ Involvement. Cureus. 2022;14(12):e32968

7. Waggoner SE. Cervical cancer. Lancet. 2003;361(9376):2217-2225

8. The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Integrated genomic and molecular characterization of cervical cancer. Nature. 2017;543(7645):378-384

9. Franco EL, Schlecht NF, Saslow D. The epidemiology of cervical cancer. Cancer J. 2003;9(5):348-359

10. De Wever O, Mareel M. Role of tissue stroma in cancer cell invasion. J Pathol. 2003;200(4):429-447

11. Paño B, Sebastià C, Ripoll E, Paredes P, Salvador R, Buñesch L. et al. Pathways of lymphatic spread in gynecologic malignancies. Radiographics. 2015;35(3):916-945

12. Alitalo A, Detmar M. Interaction of tumor cells and lymphatic vessels in cancer progression. Oncogene. 2012;31(42):4499-4508

13. Olthof EP, van der Aa MA, Adam JA, Stalpers LJA, Wenzel HHB, van der Velden J. et al. The role of lymph nodes in cervical cancer: incidence and identification of lymph node metastases-a literature review. Int J Clin Oncol. 2021;26(9):1600-1610

14. Benedetti Panici P, Basile S, Angioli R. Pelvic and aortic lymphadenectomy in cervical cancer: the standardization of surgical procedure and its clinical impact. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;113(2):284-290

15. Randolph GW, Duh QY, Heller KS, LiVolsi VA, Mandel SJ, Steward DL. et al. The prognostic significance of nodal metastases from papillary thyroid carcinoma can be stratified based on the size and number of metastatic lymph nodes, as well as the presence of extranodal extension. Thyroid. 2012;22(11):1144-1152

16. Yamaguchi S, Koizumi M, Kakuda M, Yamamoto T. Uncommon Hematogenous Metastasis: Orbital Involvement in Uterine Cervical Cancer. Am J Case Rep. 2023;24:e941076

17. Casey L, Singh N. Metastases to the ovary arising from endometrial, cervical and fallopian tube cancer: recent advances. Histopathology. 2020;76(1):37-51

18. Han T, Kang D, Ji D, Wang X, Zhan W, Fu M. et al. How does cancer cell metabolism affect tumor migration and invasion? Cell Adh Migr. 2013;7(5):395-403

19. Zeidman I. Metastasis: a review of recent advances. Cancer Res. 1957;17(3):157-162

20. Timmerman RD, Bizekis CS, Pass HI, Fong Y, Dupuy DE, Dawson LA. et al. Local surgical, ablative, and radiation treatment of metastases. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59(3):145-170

21. Fisher B. Biological research in the evolution of cancer surgery: a personal perspective. Cancer Res. 2008;68(24):10007-10020

22. Julien SG, Dubé N, Hardy S, Tremblay ML. Inside the human cancer tyrosine phosphatome. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11(1):35-49

23. Heldin CH, Lennartsson J, Westermark B. Involvement of platelet-derived growth factor ligands and receptors in tumorigenesis. J Intern Med. 2018;283(1):16-44

24. Zou X, Tang XY, Qu ZY, Sun ZW, Ji CF, Li YJ. et al. Targeting the PDGF/PDGFR signaling pathway for cancer therapy: A review. Int J Biol Macromol. 2022;202:539-557

25. Ostman A. PDGF receptors-mediators of autocrine tumor growth and regulators of tumor vasculature and stroma. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2004;15(4):275-286

26. Barreca A, Fornari A, Bonello L, Tondat F, Chiusa L, Lista P. et al. KIT and PDGFRA mutations and PDGFRA immunostaining in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Mol Med Rep. 2011;4(1):3-8

27. Guérit E, Arts F, Dachy G, Boulouadnine B, Demoulin JB. PDGF receptor mutations in human diseases. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2021;78(8):3867-3881

28. Xia X, Li WH. What amino acid properties affect protein evolution? J Mol Evol. 1998;47(5):557-564

29. Farag S, Somaiah N, Choi H, Heeres B, Wang WL, van Boven H. et al. Clinical characteristics and treatment outcome in a large multicentre observational cohort of PDGFRA exon 18 mutated gastrointestinal stromal tumour patients. Eur J Cancer. 2017;76:76-83

30. Clarke ID, Dirks PB. A human brain tumor-derived PDGFR-alpha deletion mutant is transforming. Oncogene. 2003;22(5):722-733

31. Savino S, Desmet T, Franceus J. Insertions and deletions in protein evolution and engineering. Biotechnol Adv. 2022;60:108010

32. Yeo AT, Jun HJ, Appleman VA, Zhang P, Varma H, Sarkaria JN. et al. EGFRvIII tumorigenicity requires PDGFRA co-signaling and reveals therapeutic vulnerabilities in glioblastoma. Oncogene. 2021;40(15):2682-2696

33. Valle-Mendiola A, Gutiérrez-Hoya A, Soto-Cruz I. JAK/STAT Signaling and Cervical Cancer: From the Cell Surface to the Nucleus. Genes (Basel). 2023;14(6):1141

34. Martinho O, Longatto-Filho A, Lambros MB, Martins A, Pinheiro C, Silva A. et al. Expression, mutation and copy number analysis of platelet-derived growth factor receptor A (PDGFRA) and its ligand PDGFA in gliomas. Br J Cancer. 2009;101(6):973-982

35. Longatto-Filho A, Pinheiro C, Martinho O, Moreira MA, Ribeiro LF, Queiroz GS. et al. Molecular characterization of EGFR, PDGFRA and VEGFR2 in cervical adenosquamous carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:212

36. Arias-Pulido H, Joste N, Chavez A, Muller CY, Dai D, Smith HO. et al. Absence of epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in cervical cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2008;18(4):749-754

37. Perrone F, Da Riva L, Orsenigo M, Losa M, Jocollè G, Millefanti C. et al. PDGFRA, PDGFRB, EGFR, and downstream signaling activation in malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor. Neuro Oncol. 2009;11(6):725-736

38. Teodorczyk M, Martin-Villalba A. Sensing invasion: cell surface receptors driving spreading of glioblastoma. J Cell Physiol. 2010;222(1):1-10

39. Taeger J, Moser C, Hellerbrand C, Mycielska ME, Glockzin G, Schlitt HJ. et al. Targeting FGFR/PDGFR/VEGFR impairs tumor growth, angiogenesis, and metastasis by effects on tumor cells, endothelial cells, and pericytes in pancreatic cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2011;10(11):2157-2167

40. Bou Antoun N, Afshan Mahmood HT, Walker AJ, Modjtahedi H, Grose RP, Chioni AM. Development and Characterization of Three Novel FGFR Inhibitor Resistant Cervical Cancer Cell Lines to Help Drive Cervical Cancer Research. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26(5):1799

41. Liu Y, Chen C, Xu Z, Scuoppo C, Rillahan CD, Gao J. et al. Deletions linked to TP53 loss drive cancer through p53-independent mechanisms. Nature. 2016;531(7595):471-475

42. Patil MR, Bihari A. A comprehensive study of p53 protein. J Cell Biochem. 2022;123(12):1891-1937

43. Vang R, Levine DA, Soslow RA, Zaloudek C, Shih Ie M, Kurman RJ. Molecular Alterations of TP53 are a Defining Feature of Ovarian High-Grade Serous Carcinoma: A Rereview of Cases Lacking TP53 Mutations in The Cancer Genome Atlas Ovarian Study. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2016;35(1):48-55

44. Petitjean A, Achatz MI, Borresen-Dale AL, Hainaut P, Olivier M. TP53 mutations in human cancers: functional selection and impact on cancer prognosis and outcomes. Oncogene. 2007;26(15):2157-2165

45. Walker DR, Bond JP, Tarone RE, Harris CC, Makalowski W, Boguski MS. et al. Evolutionary conservation and somatic mutation hotspot maps of p53: correlation with p53 protein structural and functional features. Oncogene. 1999;18(1):211-218

46. Liu L, Li XD, Chen HY, Cui JS, Xu DY. Significance of Ebp1 and p53 protein expression in cervical cancer. Genet Mol Res. 2015;14(4):11860-11866

47. Chen X, Zhang T, Su W, Dou Z, Zhao D, Jin X. et al. Mutant p53 in cancer: from molecular mechanism to therapeutic modulation. Cell Death Dis. 2022;13(11):974

48. Stewart ZA, Pietenpol JA. p53 Signaling and cell cycle checkpoints. Chem Res Toxicol. 2001;14(3):243-263

49. Lee SA, Kim JW, Roh JW, Choi JY, Lee KM, Yoo KY. et al. Genetic polymorphisms of GSTM1, p21, p53 and HPV infection with cervical cancer in Korean women. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;93(1):14-18

50. Ou HL, Schumacher B. DNA damage responses and p53 in the aging process. Blood. 2018;131(5):488-495

51. Ngan HY, Tsao SW, Liu SS, Stanley M. Abnormal expression and mutation of p53 in cervical cancer-a study at protein, RNA and DNA levels. Genitourin Med. 1997;73(1):54-58

52. Marei HE, Althani A, Afifi N, Hasan A, Caceci T, Pozzoli G. et al. p53 signaling in cancer progression and therapy. Cancer Cell Int. 2021;21(1):703

53. Hao Q, Chen J, Lu H, Zhou X. The ARTS of p53-dependent mitochondrial apoptosis. J Mol Cell Biol. 2023;14(10):mjac074

54. Aswathy R, Suganya K, Varghese CA, Sumathi S. Deciphering the Expression, Functional Role, and Prognostic Significance of P53 in Cervical Cancer Through Bioinformatics Analysis. J Obstet Gynaecol India. 2025;75(1):36-45

55. Muller PA, Vousden KH, Norman JC. p53 and its mutants in tumor cell migration and invasion. J Cell Biol. 2011;192(2):209-218

56. Lin J, Lu J, Wang C, Xue X. The prognostic values of the expression of Vimentin, TP53, and Podoplanin in patients with cervical cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 2017;17:80

57. Curran S, Murray GI. Matrix metalloproteinases in tumour invasion and metastasis. J Pathol. 1999;189(3):300-308

58. Cordani M, Pacchiana R, Butera G, D'Orazi G, Scarpa A, Donadelli M. Mutant p53 proteins alter cancer cell secretome and tumour microenvironment: Involvement in cancer invasion and metastasis. Cancer Lett. 2016;376(2):303-309

59. Tiwari N, Gheldof A, Tatari M, Christofori G. EMT as the ultimate survival mechanism of cancer cells. Semin Cancer Biol. 2012;22(3):194-207

60. Alam SK, Yadav VK, Bajaj S, Datta A, Dutta SK, Bhattacharyya M. et al. DNA damage-induced ephrin-B2 reverse signaling promotes chemoresistance and drives EMT in colorectal carcinoma harboring mutant p53. Cell Death Differ. 2016;23(4):707-722

61. Puisieux A, Brabletz T, Caramel J. Oncogenic roles of EMT-inducing transcription factors. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16(6):488-494

62. Xue C, Chu Q, Shi Q, Zeng Y, Lu J, Li L. Wnt signaling pathways in biology and disease: mechanisms and therapeutic advances. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2025;10(1):106

63. Szczepanek J, Tretyn A. MicroRNA-Mediated Regulation of Histone-Modifying Enzymes in Cancer: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Implications. Biomolecules. 2023;13(11):1590

64. Kuentz P, St-Onge J, Duffourd Y, Courcet JB, Carmignac V, Jouan T. et al. Molecular diagnosis of PIK3CA-related overgrowth spectrum (PROS) in 162 patients and recommendations for genetic testing. Genet Med. 2017;19(9):989-997

65. Firoozinia M, Zareian Jahromi M, Moghadamtousi SZ, Nikzad S, Abdul Kadir H. PIK3CA gene amplification and PI3K p110α protein expression in breast carcinoma. Int J Med Sci. 2014;11(6):620-625

66. Bilanges B, Posor Y, Vanhaesebroeck B. PI3K isoforms in cell signalling and vesicle trafficking. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2019;20(9):515-534

67. He Y, Sun MM, Zhang GG, Yang J, Chen KS, Xu WW. et al. Targeting PI3K/Akt signal transduction for cancer therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6(1):425

68. Rudd ML, Price JC, Fogoros S, Godwin AK, Sgroi DC, Merino MJ. et al. A unique spectrum of somatic PIK3CA (p110alpha) mutations within primary endometrial carcinomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(6):1331-1340

69. Lugano R, Ramachandran M, Dimberg A. Tumor angiogenesis: causes, consequences, challenges and opportunities. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2020;77(9):1745-1770

70. Samuels Y, Waldman T. Oncogenic mutations of PIK3CA in human cancers. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2010;347:21-41

71. Nieto-Coronel T, Alette OG, Yacab R, Fernández-Figueroa EA, Lopez-Camarillo C, Marchat L. et al. PI3K Mutation Profiles on Exons 9 (E545K and E542K) and 20 (H1047R) in Mexican Patients With HER-2 Overexpressed Breast Cancer and Its Relevance on Clinical-Pathological and Survival Biological Effects. Int J Breast Cancer. 2024;2024:9058033

72. Cochicho D, Esteves S, Rito M, Silva F, Martins L, Montalvão P. et al. PIK3CA Gene Mutations in HNSCC: Systematic Review and Correlations with HPV Status and Patient Survival. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(5):1286

73. Xiang L, Jiang W, Li J, Shen X, Yang W, Yang G. et al. PIK3CA mutation analysis in Chinese patients with surgically resected cervical cancer. Sci Rep. 2015;5:14035

74. McIntyre JB, Wu JS, Craighead PS, Phan T, Köbel M, Lees-Miller SP. et al. PIK3CA mutational status and overall survival in patients with cervical cancer treated with radical chemoradiotherapy. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;128(3):409-414

75. Hu R, Wang MQ, Niu WB, Wang YJ, Liu YY, Liu LY. et al. SKA3 promotes cell proliferation and migration in cervical cancer by activating the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Cancer Cell Int. 2018;18:183

76. Vadlakonda L, Pasupuleti M, Pallu R. Role of PI3K-AKT-mTOR and Wnt Signaling Pathways in Transition of G1-S Phase of Cell Cycle in Cancer Cells. Front Oncol. 2013;3:85

77. Voutsadakis IA. PI3KCA Mutations in Uterine Cervix Carcinoma. J Clin Med. 2021;10(2):220

78. Bahrami A, Hasanzadeh M, Hassanian SM, ShahidSales S, Ghayour-Mobarhan M, Ferns GA. et al. The Potential Value of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR Signaling Pathway for Assessing Prognosis in Cervical Cancer and as a Target for Therapy. J Cell Biochem. 2017;118(12):4163-4169

79. Bossler F, Hoppe-Seyler K, Hoppe-Seyler F. PI3K/AKT/mTOR Signaling Regulates the Virus/Host Cell Crosstalk in HPV-Positive Cervical Cancer Cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(9):2188

80. Xue G, Hemmings BA. PKB/Akt-dependent regulation of cell motility. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105(6):393-404

81. Bertelsen BI, Steine SJ, Sandvei R, Molven A, Laerum OD. Molecular analysis of the PI3K-AKT pathway in uterine cervical neoplasia: frequent PIK3CA amplification and AKT phosphorylation. Int J Cancer. 2006;118(8):1877-1883

82. Braicu C, Buse M, Busuioc C, Drula R, Gulei D, Raduly L. et al. A Comprehensive Review on MAPK: A Promising Therapeutic Target in Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11(10):1618

83. Ros J, Baraibar I, Sardo E, Mulet N, Salvà F, Argilés G. et al. BRAF, MEK and EGFR inhibition as treatment strategies in BRAF V600E metastatic colorectal cancer. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2021;13:1758835921992974

84. Lu S. Ambulatory Care Sensitive Conditions in Pediatrics: Time for a Reassessment. Pediatrics. 2021;148(2):e2021050598

85. Muthusami S, Sabanayagam R, Periyasamy L, Muruganantham B, Park WY. A review on the role of epidermal growth factor signaling in the development, progression and treatment of cervical cancer. Int J Biol Macromol. 2022;194:179-187

86. Liu Q, Yu S, Zhao W, Qin S, Chu Q, Wu K. EGFR-TKIs resistance via EGFR-independent signaling pathways. Mol Cancer. 2018;17(1):53

87. Cheng JC, Chou CH, Kuo ML, Hsieh CY. Radiation-enhanced hepatocellular carcinoma cell invasion with MMP-9 expression through PI3K/Akt/NF-kappaB signal transduction pathway. Oncogene. 2006;25(53):7009-7018

88. Wang K, Hattori S, Kang S, Lin M, Yoshida N. Isotopic constraints on the formation pathways and sources of atmospheric nitrate in the Mt. Everest region. Environ Pollut. 2020;267:115274

89. Schrank TP, Kim S, Rehmani H, Kothari A, Wu D, Yarbrough WG. et al. Direct Comparison of HPV16 Viral Genomic Integration, Copy Loss, and Structural Variants in Oropharyngeal and Uterine Cervical Cancers Reveal Distinct Relationships to E2 Disruption and Somatic Alteration. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(18):4488

90. Moody CA, Laimins LA. Human papillomavirus oncoproteins: pathways to transformation. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10(8):550-560

91. Gbala I, Kavcic N, Banks L. The retinoblastoma protein contributes to maintaining the stability of HPV E7 in cervical cancer cells. J Virol. 2025;99(4):e0220324

92. Chen J. Signaling pathways in HPV-associated cancers and therapeutic implications. Rev Med Virol. 2015;25(Suppl 1):24-53

93. Kim HJ, Lee HN, Jeong MS, Jang SB. Oncogenic KRAS: Signaling and Drug Resistance. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(22):4488

94. Kapoor A, Travesset A. Differential dynamics of RAS isoforms in GDP- and GTP-bound states. Proteins. 2015;83(6):1091-1106

95. Li C, Vides A, Kim D, Xue JY, Zhao Y, Lito P. The G protein signaling regulator RGS3 enhances the GTPase activity of KRAS. Science. 2021;374(6564):197-201

96. Vivanco I, Sawyers CL. The phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase AKT pathway in human cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2(7):489-501

97. Ternet C, Kiel C. Signaling pathways in intestinal homeostasis and colorectal cancer: KRAS at centre stage. Cell Commun Signal. 2021;19(1):31

98. Jiang W, Xiang L, Pei X, He T, Shen X, Wu X. et al. Mutational analysis of KRAS and its clinical implications in cervical cancer patients. J Gynecol Oncol. 2018;29(1):e4

99. Lohinai Z, Klikovits T, Moldvay J, Ostoros G, Raso E, Timar J. et al. KRAS-mutation incidence and prognostic value are metastatic site-specific in lung adenocarcinoma: poor prognosis in patients with KRAS mutation and bone metastasis. Sci Rep. 2017;7:39721

100. Peng Y, Yang Q. Targeting KRAS in gynecological malignancies. Faseb j. 2024;38(19):e70089

101. Su WH, Chuang PC, Huang EY, Yang KD. Radiation-induced increase in cell migration and metastatic potential of cervical cancer cells operates via the K-Ras pathway. Am J Pathol. 2012;180(2):862-871

102. Nakamura Y, Yokoyama S, Matsuda K, Tamura K, Mitani Y, Iwamoto H. et al. Preoperative detection of KRAS mutated circulating tumor DNA is an independent risk factor for recurrence in colorectal cancer. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):441

103. Eksteen C, Riedemann J, Rass AM, Plessis MD, Botha MH, van der Merwe FH. et al. A Review: Genetic Mutations as a Key to Unlocking Drug Resistance in Cervical Cancer. Cancer Control. 2024;31:10732748241261539

104. Haddadi N, Lin Y, Travis G, Simpson AM, Nassif NT, McGowan EM. PTEN/PTENP1: 'Regulating the regulator of RTK-dependent PI3K/Akt signalling', new targets for cancer therapy. Mol Cancer. 2018;17(1):37

105. Wu H, Goel V, Haluska FG. PTEN signaling pathways in melanoma. Oncogene. 2003;22(20):3113-3122

106. Harima Y, Sawada S, Nagata K, Sougawa M, Ostapenko V, Ohnishi T. Mutation of the PTEN gene in advanced cervical cancer correlated with tumor progression and poor outcome after radiotherapy. Int J Oncol. 2001;18(3):493-497

107. Peralta-Zaragoza O, Deas J, Meneses-Acosta A, De la OGF, Fernández-Tilapa G, Gómez-Cerón C. et al. Relevance of miR-21 in regulation of tumor suppressor gene PTEN in human cervical cancer cells. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:215

108. Pao CC, Hor JJ, Yang FP, Lin CY, Tseng CJ. Detection of human papillomavirus mRNA and cervical cancer cells in peripheral blood of cervical cancer patients with metastasis. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15(3):1008-1012

109. Galvano A, Castellana L, Gristina V, La Mantia M, Insalaco L, Barraco N. et al. The diagnostic accuracy of PIK3CA mutations by circulating tumor DNA in breast cancer: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2022;14:17588359221110162

110. Krishnan S, Chadha AS, Suh Y, Chen HC, Rao A, Das P. et al. Focal Radiation Therapy Dose Escalation Improves Overall Survival in Locally Advanced Pancreatic Cancer Patients Receiving Induction Chemotherapy and Consolidative Chemoradiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2016;94(4):755-765

111. Xu W, Xu M, Wang L, Zhou W, Xiang R, Shi Y. et al. Integrative analysis of DNA methylation and gene expression identified cervical cancer-specific diagnostic biomarkers. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2019;4:55

112. Pulumati A, Pulumati A, Dwarakanath BS, Verma A, Papineni RVL. Technological advancements in cancer diagnostics: Improvements and limitations. Cancer Rep (Hoboken). 2023;6(2):e1764

113. Barentsz J, Takahashi S, Oyen W, Mus R, De Mulder P, Reznek R. et al. Commonly used imaging techniques for diagnosis and staging. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(20):3234-3244

114. Duffy MJ. Clinical uses of tumor markers: a critical review. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2001;38(3):225-262

115. Gu J, Wang D, Huang Y, Lu Y, Peng C. Diagnostic value of combining CA 19-9 and K-ras gene mutation in pancreatic carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2014;7(10):3225-3234