Impact Factor

ISSN: 1449-1907

Int J Med Sci 2026; 23(3):950-962. doi:10.7150/ijms.119158 This issue Cite

Research Paper

Gut Microbiota Signatures and Potential Mediators in the Trajectory of Age-related Macular Degeneration: A Phased Atlas by Genetic Inference

1. Department of Ophthalmology, Shanghai Tenth People's Hospital, School of Medicine, Tongji University, 301 Middle Yanchang Road, Shanghai, China

2. Department of Ophthalmology, Shanghai Sixth People's Hospital, School of Medicine, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, China

3. Beijing Tongren Eye Center, Beijing Tongren Hospital, Beijing Ophthalmology and Visual Science Key Lab, Capital Medical University, NO.1 Dongjiaominxiang Street, Dongcheng District, Beijing, China, 100730

4. Center of Basic Medical Research, Institute of Medical Innovation and Research, Peking University Third Hospital, No. 49 North Garden Road, Haidian District, Beijing, China

5. Department of Functional Intestinal Diseases, General Surgery of Shanghai Tenth People's Hospital, Tongji University School of Medicine, 301 Middle Yanchang Road, Shanghai, China

6. School of Clinical Medicine, Shanghai University of Medicine & Health Sciences, Shanghai 201318, China

†Equal contribution.

Received 2025-6-8; Accepted 2026-1-9; Published 2026-2-4

Abstract

Purpose: To depict an atlas of stage-stratified gut microbiota (GM) signatures and intermediatory metabolites, inflammatory proteins, and immune cell traits, governing the AMD trajectory.

Methods: We deployed bidirectional two-sample Mendelian randomization (TSMR) integrating GWAS data of 207 GM taxa from the Dutch Microbiome Project (N = 7,738), and multiple AMD stages/subtypes, including 'Macular degeneration (senile) of retina', 'Early AMD', 'Disease progression to GA/CNV', 'Dry AMD includes GA', and 'Wet AMD', encapsulating the disease trajectory (N > 410,000), complemented by multivariable MR (MVMR) mediation analysis of 1,400 circulating metabolites, 731 immune cell traits, and 91 inflammatory proteins.

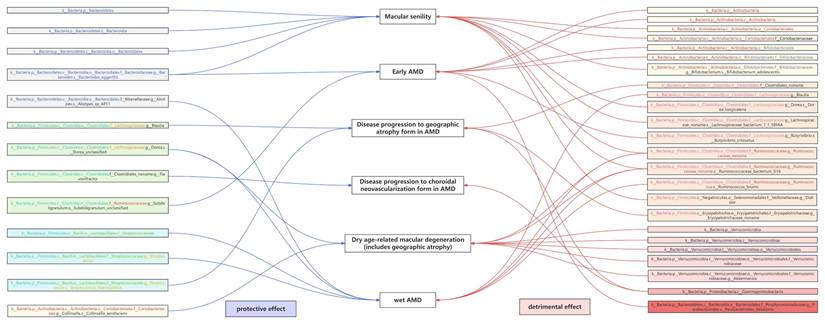

Results: We identified 12/8/5/2/9/8 genetically predicted causal GM taxa of various AMD stages/subtypes as a stage-stratified GM signature across the AMD trajectory, among which g.Ruminococcaceae and s.Ruminococcaceae_bacterium_D16 were the sole shared GM taxa in triple AMD stages, while s.Bacteroides eggerthii, c.Gammaproteobacteria, s.Dorea and s.Ruminococcus_obeum influence dual AMD stages. Bidirectional analysis revealed that f.Streptococcaceae, g.Erysipelotrichaceae_noname, g.Streptococcus, s.Streptococcus_thermophilus, g.Ruminococcaceae_noname, and s.Ruminococcaceae_bacterium_D16 exhibited genetically reciprocal causation with AMD. We also proposed that Firmicutes may exhibit stage-specific duality depending on their constituent members and AMD stages. Several understudied GM from p.Actinobacteria and p.Verrucomicrobia have been implicated as AMD-associated taxa for the first time. Key metabolites, immune cell traits, and inflammatory proteins were established as significant mediators of GM-AMD links.

Conclusions: This first phased atlas uncovers GM effects over the AMD course, identifying potential microbial and biochemical targets for intervening in disease development.

Keywords: age-related macular degeneration, gut microbiota, Mendelian randomization, mediation analysis

1. Introduction

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD), the leading cause of irreversible central vision loss in elderly populations [1], retains unresolved pathophysiological complexity despite decades of research [2]. Emerging insights into the "eye-gut axis" implicate gut microbiota (GM) dysbiosis as a potential AMD modulator [3, 4], with proposed mechanisms involving immune-metabolic cross-talk [5, 6]. Intriguingly, GM interactions align with AMD risk factors spanning aging, metabolic disorders, and lifestyle behaviors [7]. Yet, critical knowledge gaps persist in this burgeoning area: a) Methodological constraints: The vast majority of existing studies are confined to 16sRNA GM sequencing reports with limited sample sizes, restricting taxonomic resolution to genus level and lacking the statistical power to detect clinically meaningful associations. More importantly, clinical observations merely document microbial abundance alterations without characterizing pathogenic/protective functional roles of specific taxa; b) Temporal blindness: Cross-sectional sampling of patients in single AMD stage fails to capture dynamic GM shifts across AMD trajectory [8], which is a limitation common to clinical observation of GM in other diseases as well; c) Confounding entanglement: Inherent susceptibility of GM to AMD risk factors (diet, medications, comorbidities) creates insurmountable confounding in observational studies, perpetuating causal ambiguity. Additionally, clinical trials concerning GM-AMD may encounter cost and ethical challenges. As such, ascertaining causal disease-associated GM taxa and investigating GM's impacts throughout the disease course are desiderata in this field, before further mechanistic research and therapeutic development take out [7].

Building upon the current literature, the present study seeks to bridge these knowledge gaps by an integrated analytical framework of Mendelian Randomization (MR), a robust analytical technique for establishing causality through genetic instrumental variables, widely accepted as an alternative method for assessing the causal effects of related factors on diseases [9]. While AMD possesses a multifactorial etiology, the genetic predisposition to AMD remains highly non-negligible, as evidenced by familial and twin studies [10-13]. Key AMD risk loci such as CFH (chromosome 1q32), ARMS2/HTRA1 (10q26), and APOE (19q13) have been identified through genetic susceptibility research [14, 15]. Notably, gene-environment synergism, such as the smoking-LOC387715 interactions, may elevate AMD risk, underscoring the genetic interplay between susceptibility genes and environmental risk factors [16-18].

The present study adopts an intricate design to utilize the SNP-heritability in AMD and GM. First, we obtained GM data from the Dutch Microbiome Project (DMP), the largest GWAS dataset that provides GM information from phylum to species level. Next, to investigate the GM role in a lengthy disease trajectory, we employed a diverse array of GWAS datasets of various AMD stages/subtypes, spanning preclinical senile degeneration of macula, early AMD, SNPs representing disease progression to two major advanced events: choroidal neovascularization (CNV)/geographic atrophy (GA), and the advanced wet/dry subtypes, to represent the whole disease course. We employed a bidirectional two-sample MR (TSMR) to elucidate directional causality and causal effects of GM on AMD progression. By leveraging the random assortment of genetic variants during meiosis, MR facilitates causal inference comparable to that of a randomised controlled trial, thereby reducing the impact of confounding factors and the bias of reverse causation that often arise in observational studies. More importantly, MR allows for the integration of multiple distinct GWAS cohorts, which reduces sampling bias and makes it feasible to investigate the GM role at various AMD stages. Together, we aim to depict a longitudinal atlas with stage-stratified GM signatures of the AMD trajectory through genetically predicted causality. Moreover, to further elucidate the potential mechanisms underlying the causal GM-AMD relationships, we incorporated potential mediatory candidates, including circulating metabolites, inflammatory proteins, and immune cell traits for mediation analysis.

2. Material and Methods

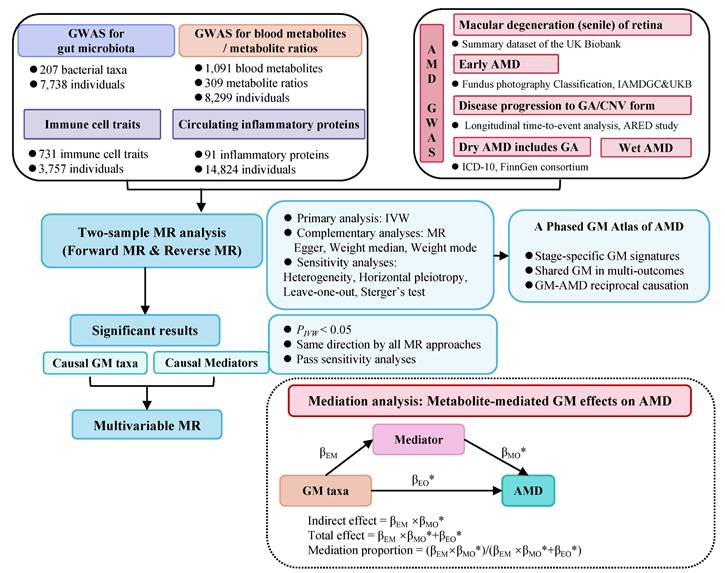

2.1 Overall survey design

The overarching design of our study is illustrated in Figure 1. Initially, we harnessed summary GWAS data of a) exposure: the DMP cohort b) outcomes: a variety of GWAS cohorts of different AMD stages/subtypes representing the disease trajectory. We employed a two-sample Mendelian randomization (TSMR) approach, which enables investigation of causal impacts from GM exposure on various AMD cohorts (outcomes), thereby capacitating a comprehensive genetic report of the GM role in the trajectory of AMD. Subsequently, sensitivity analyses, including a reverse MR analysis, were conducted to affirm the robustness and directional consistency of the TSMR findings. To further elucidate the mediating pathways from GM to AMD, we employed a two-step mediation analysis and a multivariable MR (MVMR) approach for focused mediation analysis on specific metabolites, inflammatory proteins, and immune cell traits.

A synopsis of the research framework.

2.2 Data sources

2.2.1 Gut microbiota

The European GWAS summary dataset for GM originates from the Dutch Microbiome Project (DMP), encompassing 7,738 individuals of European ancestry [19]. The DMP examines the gut microbiome composition of participants from the Lifelines study, a renowned population-based cohort from a specific geographic region in the northern Netherlands. Utilizing shotgun metagenomic sequencing of faecal samples, the DMP incorporated a comprehensive taxonomic classification consisting of 207 GM taxa (spanning 5 phyla, 10 classes, 13 orders, 26 families, 48 genera, and 105 species).

2.2.2 Various AMD stages/subtypes

Genetic variations associated with 'Macular degeneration (senile) of retina', referring to a broader definition of age-related degenerative changes in the macula lutea of the retina, were derived from a summary dataset of the UK Biobank (GCST90043776), comprising 456,348 white British participants of European descent.

Genetic variations of the onset of early AMD risk were sourced from a meta-analysis of GWAS data, including 11 data sources such as the International AMD Genomics Consortium (IAMDGC) and the UKB [20]. This analysis encompassed 105,248 individuals of European ancestry, with 14,034 cases and 91,214 controls, classified based on colour fundus photography of early AMD phenotypes. Early AMD is recognized for its distinct genetic profile compared to advanced AMD at later stages. To our knowledge, it is the largest and most comprehensive dataset focused exclusively on early AMD. Detailed information of participants from these 11 population-based cohort sources, and further introduction to early AMD classification and GWAS information may be kindly found in the original publication [20].

To focus on the genetic variations representing dynamic AMD progressions and diverse AMD trajectories, we obtained genetic information from a genome-wide bivariate time-to-event analysis of 2,721 Caucasians [21], a rare GWAS dataset of a longitudinal Genome-wide bivariate time-to-event analysis on survival outcome (CNV or GA), with a mean follow-up time of 12 years in AMD patients. According to its survival outcomes, we managed to identify specific genetic variations of 'Disease progression to geographic atrophy form in AMD' (GCST005360) and 'Disease progression to choroidal neovascularization form in AMD' (GCST005358). To our knowledge, it is the first GWAS study of disease progression (bivariate survival outcome) in AMD genetic studies, providing novel insights into the genetic predisposition in AMD development [21].

Genetic variations associated with advanced AMD were sourced from the most recent data available in the Finnish Biobank (Finngen, R11), a large-scale research project that includes genome and health data from 500,000 hospital- and population-based Finnish biobank participants [22], which provided a clear delineation of the 'wet form' of AMD and the 'Dry age-related macular degeneration (includes geographic atrophy)'.

To the best of our knowledge, no prior study has enrolled sufficient patients with AMD at various stages/subtypes, nor conducted longitudinal observation tracking the entire disease progression in a large number of patients, to fulfill the investigation across the disease trajectory. Here, we integrated six GWAS datasets, each representing a distinct AMD stage or subtype. Together, utilizing a two-sample MR analysis, we may be able to conduct the investigation of GM's impacts over the disease course to some extent. On the other hand, we may reveal quite a few shared GM taxa across multiple AMD stages/subtypes with causalities in the current study. Consistent findings across multiple cohorts carry greater predictive potential and clinical relevance. Therefore, alongside revealing a stage-stratified GM signature across the AMD trajectory, this integrated MR framework may also highlight shared causal GM taxa results across multi-AMD cohorts, thereby underscoring pivotal microbial targets warranting primary attention in future observation and mechanism research in this area.

2.2.3 Circulating metabolites

The GWAS summary dataset for plasma metabolites was sourced from a Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (CLSA) cohort, which included 8,299 individuals, encompassing 1,091 circulating metabolites and 309 metabolite ratios [23].

2.2.4 91 inflammatory proteins

We integrated GWAS data on 91 circulating inflammatory proteins from a meta-analysis of 11 cohorts involving 14,824 European ancestry participants [24].

2.2.5 731 immune cell traits

Summary statistical data of 731 immune-related whole-genome features were obtained from 3,757 individuals of European ancestry [25]. The immune features encompass median fluorescence intensity reflecting surface antigen levels (MFI, n = 389), absolute and relative cell counts (AC, n = 118; RC, n = 192), and morphological parameters (MP, n = 32), which encompass mature stages of CDCs, monocytes, myeloid cells, TBNK (T cells, B cells, and NK cells), and Treg panels.

2.3 Instrumental variable selection

To identify robust instrumental variables (IVs), we applied stringent criteria. GM GWAS datasets rely on sequencing of fecal samples, which is relatively costly, leading to relatively fewer participants. Under these circumstances, the application of a relaxed p < 1×10 -5 thresholds due to the polygenic nature of GM traits and limited SNP availability at stricter thresholds (p < 5×10 -8) has been widely accepted in the majority of microbiome MR studies [26-28]. Similarly, for IVs related to GM data and inflammatory proteins in the present study, we employed a relaxed GWAS significance threshold of p < 1*10^-5 for exposure-associated SNPs, ensuring adequate SNP quantity. We adhered to the conventional GWAS thresholds for SNPs associated with AMD and plasma metabolites (p < 5*10^-8). Subsequently, we employed a chained unbalanced aggregation method to filter out SNPs in linkage disequilibrium (LD) with one another, using an LD threshold of R2 < 0.001, a clumping distance of greater than 10,000 kb, and reference data from the 1000 Genomes Project European samples, thus minimizing the selection of SNPs in LD and preserving the independence of each SNP as a distinct source of genetic variation. We further selected SNPs with effect allele frequencies above 0.01 and excluded those with F-statistics below 10 to ensure the strength of the relationship between SNPs and exposure. F-statistics were derived using the formula F = Beta^2 / SE^2.

2.4 Statistical analyses

2.4.1 Bidirectional Two-sample Mendelian Randomization

Initially, we employed a conventional two-sample univariate Mendelian randomization (UVMR) approach to assess the causal relationships between GM and AMD. For exposures with a single IV, the Wald ratio was utilized to infer causality. When exposures involved multiple IVs, we employed inverse variance-weighted (IVW), MR-Egger, Weighted median, and Weighted mode methods to ascertain causality, with IVW serving as the primary analysis. In brief, IVW synthesized SNP-specific Wald estimates using random effects to derive a consolidated estimate of causal effects. A reverse MR analysis was conducted to verify the direction of causality, specifically, to determine if an AMD subtype could potentially causally affect GM abundance. The reverse MR methods paralleled the forward MR approach, merely designating AMD as the exposure and GM as the outcome. For MR results to be considered significant, reliance on IVW analysis was paramount, and we also required that the correlation coefficients across all 4 MR methods be consistently directed to ensure the robustness of our estimations.

2.4.2 Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses were conducted to ascertain the robustness of the inferred causal relationships. We assessed directional pleiotropy by examining the intercept of the MR-Egger regression; a non-zero intercept with p values < 0.05 was interpreted as a statistically significant indication of genetic pleiotropy [29]. Heterogeneity among the IVs was evaluated using Cochran's Q test, where smaller p values suggest greater heterogeneity and potential for directional pleiotropy. In cases where heterogeneity was detected, a random-effects IVW analysis was conducted to yield conservative and robust estimates. In the absence of heterogeneity, a fixed-effect model was applied.

Ultimately, only those causal associations involving GM that a) exhibited no heterogeneity or pleiotropy, b) demonstrated IVW results with a significance threshold of P < 0.05, and c) showed consistent directionality of correlation coefficients across all 4 causality evaluation modes were advanced to mediation analysis.

2.4.3 Mediation analysis

Mediation analysis was conducted to elucidate the potential mechanisms underlying the causal relationship between GM and AMD through circulating metabolites. We applied a two-step Mendelian randomization [30], enriched with the multivariable Mendelian randomization (MVMR) [31].

Initially, the causal relationships between GM and metabolites were assessed using two-sample MR methods to estimate the effect size βEM. Subsequently, the causal relationships between metabolites and AMD were evaluated to estimate the effect size βMO. The directions of βEM, βMO, and βEO were tested following the logical framework outlined below. Lastly, MVMR was utilized to evaluate the causal effects of mediators on outcomes (βMO*), adjusting for exposure effects (βEO*) [32]. Mediators with a p-value <0.05 in the MVMR-IVW were considered as the final causal mediators. The indirect effect of exposures on AMD through each mediator was calculated as the product of βEM and βMO*, while the direct effect of exposures on AMD was βEO*. The total effect was determined as the sum of the direct and indirect effects (βEM × βMO* + βEO*). Moreover, the proportion of mediation was calculated as the ratio of the indirect effect to the total effect ([βEM × βMO*] / [βEM × βMO* + βEO*]).

The correlation coefficients of the indirect effect, direct effect, and total effect must be consistent or adhere to the following logic: if the total effect βEO is positive, then both βEM and βMO should be either positive or negative; if the total effect βEO is negative, then βEM and βMO should be of opposite signs. Mediators that do not conform to this directional logic were excluded from further mediation analysis.

2.4.5 Software

All analyses were conducted in the R Studio environment, utilizing R version 4.3.1. We employed the R packages “TwoSampleMR,” “MendelianRandomisation,” and “MVMR”.

3. Results

The GWAS source information was displayed in Table 1, and the number of SNPs used as IVs was presented in Table S1. All SNPs exhibited satisfactory validity, and all F values were greater than 10, as shown in Table S1.

GWAS data source

| Items | GWAS ID | Size |

|---|---|---|

| Exposure | ||

| Gut microbiota | GCST90027446-GCST90027857 | 7,738 |

| Mediator | ||

| 1400 Circulating Metabolites 731 Immune Cell traits 91 Inflammatory Proteins | GCST90199621-90201020 GCST0001391-GCST0002121 GCST90274758-GCST90274848 | 8,299 3,757 14,824 |

| Outcome | ||

| Macular degeneration (senile) of retina | GCST90043776 | 456,348 |

| Early age-related macular degeneration | GCST010723 | 105,248 |

| Disease progression to geographic atrophy form in AMD | GCST005360 | 2,721 |

| Disease progression to choroidal neovascularization form in AMD | GCST005358 | |

| Dry age-related macular degeneration (includes geographic atrophy) | https://www.finngen.fi/en/access_resultshttps://r11.finngen.fi/ | 306,075 |

| Wet age-related macular degeneration | 306,042 | |

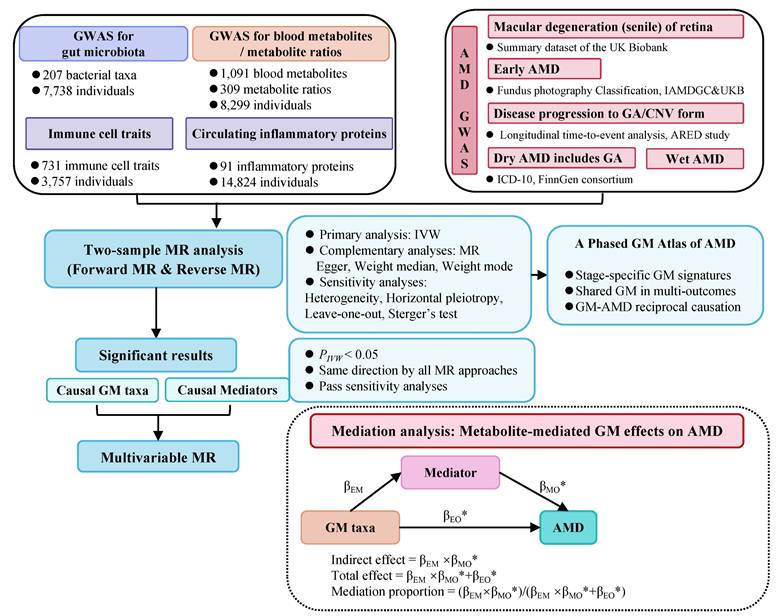

Overview of MR analyses estimating causal GM taxa and AMD across various stages. Volcano plots exhibit the causal impact of gut microbiota on AMD from the inverse variance weighted (IVW) method. The X-axis represents the logarithmic odds ratio (OR), and the Y-axis represents the -log10(PIVW). The exposure with PIVW < 0.05 and OR >1 is indicated in red, while the exposure with PIVW <0.05 and OR <1 is indicated in blue. Heatmaps outline the significant gut microbiota identified in forward MR analysis.

3.1 Bidirectional MR results of causal 'GM-AMD' links

We identified 12/8/5/2/9/8 GM taxa associated with macular degeneration (senile) of retina, early AMD, disease progression to GA/CNV, dry AMD includes GA, and wet AMD, respectively, in the forward MR analysis (Figure 2).

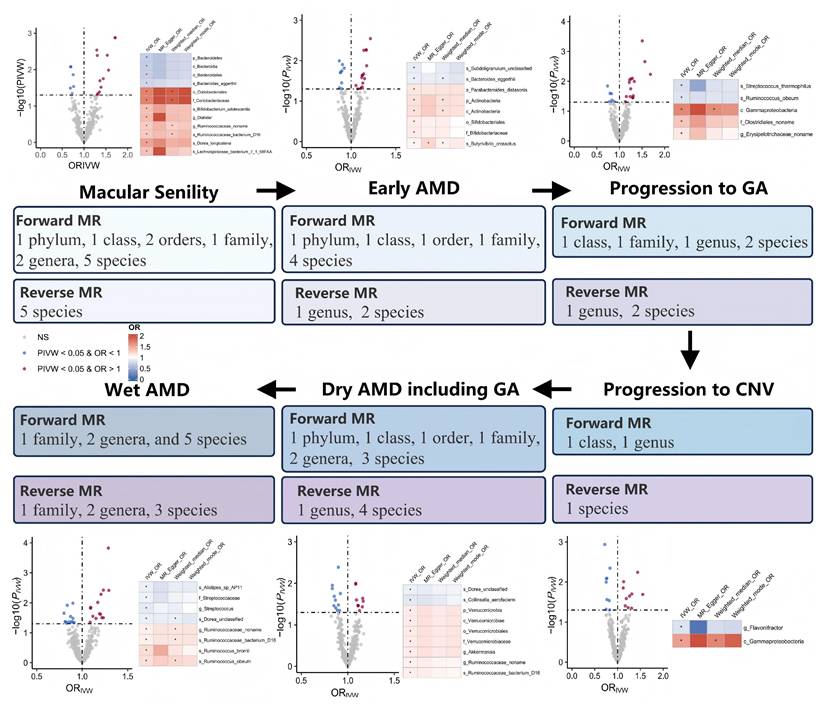

Notably, g.Ruminococcaceae noname and its subordinate s.Ruminococcaceae bacterium D16 were the only shared GM taxa of triple AMD stages with consistent and positive associations (all Pivw values < 0.05, OR > 1, Table 2). We also revealed another 4 specific GM taxa shared from dual AMD stages. C.Gammaproteobacteria is one contributing taxon for both disease progression to GA and CNV (OR: 1.687, 95% CI: 1.163-2.446; OR: 1.552, 95% CI: 1.070-2.251). On the other hand, s.Dorea unclassified exhibited as a protective taxon for the two advanced events (wet AMD, OR: 0.898, 95% CI: 0.828-0.975; dry AMD includes GA, OR: 0.899, 95% CI: 0.837-0.967). Meanwhile, s.Bacteroides eggerthii was also revealed as a potential protective taxon for macular degeneration (senile) of retina and early AMD risk (macular degeneration (senile) of retina, OR: 0.751, 95% CI: 0.599-0.943; early AMD, OR: 0.903, 95% CI: 0.834-0.978). Additionally, s.Ruminococcus obeum has divergent impacts on disease progression to GA and wet AMD (disease progression to GA, OR: 0.824, 95% CI: 0.695-0.977; wet AMD, OR: 1.171, 95% CI: 1.039-1.320). A complete stage-stratified causal GM signature predicted by forward MR may be found in Table S1 & Figure 3.

Genetically Predicted Causal beneficial or detrimental GM taxa associated with AMD at different stages.

Shared GM taxa of multi-AMD stages/subtypes in forward MR analysis

| GM taxa as Exposure | IVW Estimate |

|---|---|

| OR (95%CI) | |

| genus_Ruminococcaceae_noname | |

| Macular degeneration (senile) of retina | 1.292 (1.091-1.529) |

| Dry age-related macular degeneration (includes geographic atrophy) | 1.086 (1.019-1.156) |

| Wet AMD | 1.093 (1.018-1.173) |

| species_Ruminococcaceae_bacterium_D16 | |

| Macular degeneration (senile) of retina | 1.304 (1.088-1.562) |

| Dry age-related macular degeneration (includes geographic atrophy) | 1.086 (1.020-1.157) |

| Wet AMD | 1.092 (1.017-1.173) |

| class_Gammaproteobacteria | |

| Disease progression to geographic atrophy form in AMD | 1.687 (1.163-2.446) |

| Disease progression to choroidal neovascularization form in AMD | 1.552 (1.070-2.251) |

| species_Bacteroides_eggerthii | |

| Macular degeneration (senile) of retina | 0.751 (0.599-0.943) |

| Early AMD | 0.903 (0.834-0.978) |

| species_Dorea_unclassified | |

| Dry age-related macular degeneration (includes geographic atrophy) | 0.899 (0.837-0.967) |

| Wet AMD | 0.898 (0.828-0.975) |

| species_Ruminococcus_obeum | |

| Disease progression to geographic atrophy form in AMD | 0.824 (0.695-0.977) |

| Wet AMD | 1.171 (1.039-1.320) |

Footnotes: Causal associations are demonstrated by significant IVW estimates (P < 0.05), with consistent directionality of correlation coefficients across all 4 causality evaluation modes.

When AMD served as the exposure variable, the reverse MR analysis revealed 23 significant correlations between AMD and GM, including 4 pairs of GM taxa results shared from dual AMD stages, suggesting the modification effects of AMD on microbial shifts (Table S2). Crucially, the bidirectional MR analyses revealed several instances of reciprocal causality warranting particular attention (Table 3). Notably, the abundance of the disease-contributing GM taxa, g.Ruminococcaceae noname and its subordinate s.Ruminococcaceae bacterium D16 for dry/wet AMD may also be elevated by both dry and wet AMD (all OR > 1, all PIVW < 0.05 in bidirectional MR analyses). Similarly, g.Erysipelotrichaceae_noname's dual role of both a mediator and amplifier was also noticed in disease progression to GA (forward MR, OR: 1.132, 95% CI: 1.001-1.280; reverse MR, OR: 1.299, 95% CI: 1.033-1.634). Interestingly, f.Streptococcaceae and its subordinate g.Streptococcus exhibited discordant bidirectional effects with wet AMD (forward MR, OR < 1; reverse MR, OR > 1, all PIVW < 0.05). Specifically, s.Streptococcus thermophilus (under g.Streptococcus) may reduce the risk of GA development (forward MR, OR < 1), while macular degeneration (senile) of retina may also decrease its abundance (reverse MR, OR < 1).

3.2 Bidirectional MR results of causal 'circulating metabolite-AMD' links

We identified 71/104/79/54/77/106 genetically predicted causal circulating metabolites, categorized into 11 significant categories including amino acids, carbohydrates, cofactors and vitamins, energy, lipid, nucleotide, partially characterized molecules, peptides, xenobiotics and metabolites ratios, as potential mediators for macular degeneration (senile) of retina, early AMD, disease progression to GA/CNV, and dry/wet AMD, respectively (Figure 4). A complete stage-stratified causal metabolite signature may be found in Table S3, and the reverse MR results of AMD impacts on circulating metabolites were exhibited in Table S4.

The upper part is the Circular heatmap of causal circulating metabolite levels/ratios of AMD. From the outside to the inside, they are, respectively, the name of metabolites, the P value and OR based on the IVW, MR Egger results, Weighted median, and Weighted mode approaches. The innermost circle exhibits 12 categories of causal metabolites including amino acids, carbohydrate, cofactors and vitamins, energy, lipid, nucleotide, partially characterized molecules, peptide, unknown metabolite, xenobiotics, and metabolite ratios; The lower part is the Manhattan plot of MR results for all 1400 metabolite levels/ratios of AMD, with the horizontal black lines indicating significant associations at PIVW<0.05.

GM taxa holding bidirectional causations with AMD

| Reverse MR | AMD as Exposure | Causal GM taxa | AMD as Outcome | Forward MR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inverse variance weighted | Inverse variance weighted | ||||

| OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | ||||

| 1.107 (1.027-1.194) | Dry AMD (includes GA) | g.Ruminococcaceae noname | Macular degeneration (senile) of retina | 1.292 (1.091-1.529) | |

| Dry AMD (includes GA) | 1.086 (1.019-1.156) | ||||

| 1.081 (1.010-1.157) | Wet AMD | ||||

| Wet AMD | 1.093 (1.018-1.173) | ||||

| 1.110 (1.030-1.198) | Dry AMD (includes GA) | s.Ruminococcaceae bacterium D16 | Macular degeneration (senile) of retina | 1.304 (1.088-1.562) | |

| Dry AMD (includes GA) | 1.086 (1.020-1.157) | ||||

| 1.080 (1.009-1.157) | Wet AMD | ||||

| Wet AMD | 1.092 (1.017-1.173) | ||||

| 1.299 (1.033-1.634) | Disease progression to GA | g.Erysipelotrichaceae noname | Disease progression to GA | 1.132 (1.001-1.280) | |

| 1.051 (1.004-1.101) | Wet AMD | f.Streptococcaceae | Wet AMD | 0.913 (0.835-0.998) | |

| 1.054 (1.005-1.106) | Wet AMD | g.Streptococcus | Wet AMD | 0.872 (0.771-0.986) | |

| 0.843 (0.718-0.989) | Macular degeneration (senile) of retina | s.Streptococcus thermophilus | Disease progression to GA | .645-0.972) |

3.3 MR results of causal 'immune cell trait/inflammatory protein-AMD' links

In the same way, we identified 31/78/22/32/46/52 genetically predicted causal immune cell traits as potential mediators for macular degeneration (senile) of retina, early AMD, disease progression to GA/CNV, and dry/wet AMD, respectively. The complete stage-stratified causal immune cell signatures are detailed in Table S5. Regarding inflammatory proteins, 3/2/3/6/12 were implicated as potential mediators for early AMD, disease progression to GA/CNV, and dry/wet AMD, respectively, while no significant mediators were found for macular degeneration (senile) of the retina. The corresponding results for inflammatory proteins are presented in Table S6.

3.4 Mediation analysis of causal 'GM-AMD' relationships

A two-step mediation analysis, complemented by validation through MVMR analysis, was utilized to evaluate the independent effects of candidate mediators (circulating metabolites/immune cell traits/inflammatory proteins) and exposures (GM) on AMD outcomes. This robust analytical framework ascertained a reliable prediction of causal 'GM-mediator-AMD' pathways. In accordance with the foundational principles of a two-step MR analysis for mediation analysis, we first investigated the causal relationships between causal GM taxa and causal circulating metabolites/immune cell traits/inflammatory proteins in AMD (Table S7, S8, and S9).

Then, based on significant results of the preliminary 2-sample MR analysis, the MVMR approach was employed to ascertain the independent effects of candidate mediators and exposures on the AMD outcomes (Table S10). The MVMR analysis pinpointed 17 key metabolites established as significant mediators of the causal relationships between GM and AMD. Among these, 6 metabolite levels/ratios, N-acetylputrescine, 2-o-methylascorbic acid, 1-oleoyl-2-arachidonoyl-GPE (18:1/20:4), Glycochenodeoxycholate glucuronide (1), Imidazole lactate, and Androsterone glucuronide to etiocholanolone glucuronide ratio were shared mediators in multiple 'GM-AMD' links, warranting specific attention. As for immune cell traits, CD20 on unswitched memory B cell, CD45RA on resting CD4 regulatory T cell, and Effector Memory CD8+ T cell %CD8+ T cell were identified as causal candidates mediating GM's impacts on AMD (Table S10).

4. Discussion

The present study is the first report of a longitudinal GM atlas with stage-stratified GM signatures of the AMD trajectory by genetic causal inference. Leveraging Mendelian Randomization analysis in multi-GWAS datasets, we managed to carry out a comprehensive investigation on the gut microbiota exposure impacts throughout the AMD course for the first time. Stage-specific GM profiles revealed phase-specific microbial contributions to various AMD stages/subtypes, whereas conserved causal GM-AMD relationships across multiple disease stages implied pan-disease GM pathophysiological mechanisms. Crucially, shared GM taxa consistently identified across multiple AMD cohorts possess heightened predictive value and clinical relevance, highlighting pivotal microbial targets for future research. Furthermore, we pinpointed specific circulating metabolites and immune cell traits that mediate the impact of GM on AMD, elucidating underlying mechanisms of the 'GM-AMD' link. Together, this cautious genetic evidence provides a global perspective of the 'GM-AMD' relationship throughout the disease course by multi-omics integration, providing testable hypotheses and theoretical evidence for microbiome-targeted AMD interventions.

4.1 Reciprocal causations and bidirectional synergy loops

Among the unprecedented insights from this study, the identification of GM taxa exhibiting bidirectional causal relationships with AMD may stand out as a pivotal discovery (Table 3). Notably, g.Ruminococcaceae noname and its subspecies s.Ruminococcaceae bacterium D16 emerged as the sole GM taxa shared across triple AMD stages. Strikingly, we also revealed that both dry and wet AMD significantly contribute to the abundance increase of these taxa (dry AMD: β = 0.105, Pivw = 0.007; wet AMD: β = 0.078, Pivw = 0.025), while conversely, higher abundances of these taxa exacerbate AMD risks (β = 0.083-0.089, Pivw < 0.05). A similar bidirectional pattern was observed for g.Erysipelotrichaceae noname, which both drives and is amplified by AMD progression to GA (β = 0.262 exposure, β = 0.124 outcome; P < 0.05). These reciprocal pathogenic interplays underscore their dual role as mediators and amplifiers of AMD pathogenesis, which complements the traditional unidirectional "gut-to-retina" paradigm and suggests a self-perpetuating disease-microbiome feedback loop, warranting particular attention in future mechanism and intervention studies.

While bidirectional causality highlights a microbiome-disease codependency, the results of the Streptococcaceae family exemplify a more nuanced interplay—where taxonomic hierarchy and strain-specific functions dictate opposing roles in AMD pathogenesis. The f.Streptococcaceae encompasses diverse genera and species, with g.Streptococcus—its largest genus comprising over 100 species—exhibiting a dichotomy between pathogenic (e.g., s.Pneumoniae) and nonpathogenic strains (e.g., s.Streptococcus thermophilus, a well-characterized probiotic in the dairy industry). Forward MR identified f.Streptococcaceae, g.Streptococcus, and s.Streptococcus thermophilus as causal protective taxa against AMD (β = -0.091, -0.137, and -0.234, respectively; P < 0.05). Interestingly, reverse MR unveiled a paradox: genetic predisposition to AMD increases the abundance of f.Streptococcaceae (β = 0.050) and g.Streptococcus (β = 0.053) while suppressing the probiotic s.Streptococcus thermophilus (β = -0.234). We noticed the graded effect sizes in forward MR (|β|: s.thermophilus > g.Streptococcus > f.Streptococcaceae), which might be interpreted that probiotic species like s.thermophilus are the primary protective drivers within this taxon. Concurrently, according to the reverse MR, we may also propose that the AMD pathogenesis may selectively deplete beneficial strains (e.g., s.thermophilus) while promoting non-probiotic members of the same taxonomic hierarchy—a logical assumption with critical implications for microbiome-targeted therapies, suggesting that AMD may induce subcategory-specific microbial modulation for the first time.

4.2 Causal GM taxa shared in multi-AMD stages

Causal GM taxa across multi-AMD stages indicated potential pan-disease pathophysiological mechanisms in AMD progression, which deserve specific attention in future mechanism studies (Table 2). C.Gammaproteobacteria emerged as a key driver of both disease progressions to CNV and GA in our MR analysis. This genetic prediction aligns with our prior sequencing report, the only existing literature concerning Proteobacteria in AMD, suggesting a p.Proteobacteria enrichment in wet AMD patients [8]. It is noteworthy that many common human pathogens fall under the p.Proteobacteria (e.g., Escherichia, Pseudomonas), characterized by their outer membrane composition rich in lipopolysaccharides (LPS) [33]. Our mediation analysis further suggested that c.Gammaproteobacteria may disrupt homostachydrine levels and glycine-phosphate ratios. This is mechanistically consistent with a metabolomic study identifying glycine and adenosine monophosphate as central nodes in AMD metabolic networks [34]. Glycine deficiency has been considered a well-characterized hallmark of AMD, and Gly is a functional amino acid against LPS-induced injury and inflammatory stress [35, 36], implying a Gammaproteobacteria-driven shunting of glycine into glutathione synthesis to counteract oxidative stress, thereby depleting retinal glycine pools critical for AMD development.

The p.Bacteroidetes and most of its subordinate taxa may prevent AMD risk from multiple stages in the present MR prediction, shedding light on future interventional studies (Table S1 & Figure 2). From the experimental aspect, the o.Bacteroidales has been valued in protecting against early AMD pathological features induced by dietary glycemia, such as RPE hypopigmentation and atrophy [37]. Our mediation analysis further suggested that N-acetyl-putrescine may mediate the protective impacts from Bacteroidetes and its inferior members, which could be supported by previous research implying polyamines, like putrescine, as ubiquitous cellular components regulating the biological functions of RPE cells [38, 39].

Specifically, s.Bacteroides eggerthii may reduce both early AMD and macular degeneration (senile) of retina risks from our findings. RPE cells are highly enriched for the proline transporter and prefer proline as a major metabolic substrate [40-42]. The neural retina also absorbs and utilizes intermediates from proline catabolism, and the metabolic disruptions of proline may lead to retinal degenerative diseases, such as its hydroxylation process [43]. These experimental results lend support to our mediation result of the protective impacts of s.Bacteroides eggerthii on macular degeneration (senile) of retina through the proline to the trans-4-hydroxyproline ratio. Therefore, our MR prediction might provide genetic evidence underscoring the 'Bacteroidetes-AMD' association from the perspective of the retinal metabolic ecosystem and RPE-initiated macular degeneration, echoing existing experimental conclusions.

The biological functions of the Dorea bacteria are strain-specific and host microenvironment-dependent [44]. Therefore, the association of Dorea with AMD differs from existing studies [45]. According to our MR analysis, we revealed that a specific s.Dorea_unclassified as a protective taxon for both wet AMD and dry AMD includes GA, which echoes its regulation of intestinal immune responses by inducing Treg and inhibiting the differentiation and function of Th17 cells, maintaining the integrity and stability of the intestinal mucosal barrier [44].

It is also noteworthy that the s.Ruminococcus_obeum, a propionate-producing bacterial species [46], may exert divergent impacts on disease progression to GA and wet AMD. Previous studies have outlined the abundance alterations of several Ruminococcus species in AMD conditions. S.Ruminococcus callidus is a shared taxon enriched in Chinese and Swiss AMD cohorts, while s.Ruminococcus gavus may be depleted [47]. Increased abundance of s.Ruminococcus torques has also been reported in wet AMD patients [48]. Since the present study exclusively utilized European-origin data, we highly valued compatible evidence from the existing literature, especially from cross-ethics studies implying consistent AMD-associated GM, which are more likely to be relevant to disease susceptibility or pathogenesis. Echoing the abundance alterations of multiple Ruminococcus species reported in existing literature of AMD observation, the present study provided genetically causal evidence the diverse biological impacts of s.Ruminococcus_obeum in multiple AMD subtypes.

4.3 Phylum Firmicutes, a more complex role

Nearly half of the identified causal GM taxa for the AMD trajectory are subordinating taxa under p.Firmicutes in the present study (Table S1). Prior studies tended to propose a detrimental role of p.Firmicutes in AMD, merely through individual reports suggesting specific risk-enhancing taxa such as g.Eubacterium oxidoreducens and g.Ruminococcaceae UCG-011 [49, 50], or the oversimplified Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio in certain disease conditions. These findings have been interpreted as evidence for a broad detrimental role of p.Firmicutes in AMD. However, such conclusions conflate phylum-level associations with strain-specific effects, potentially oversimplifying the complex interplay between gut microbiota composition and retinal pathology. Our comprehensive MR analysis across the full AMD disease continuum reveals a more nuanced picture: p.Firmicutes harbors both risk-amplifying (1 family, 3 genera, and 6 species) and protective taxa (1 family, 2 genera, and 4 species), depending on taxonomic resolution and disease stage, suggesting a hierarchical duality within p.Firmicutes, where divergent effects of its constituent taxa collectively shape AMD pathogenesis. This taxon-specific dichotomy complements the oversimplified 'phylum-level harm' paradigm and underscores the need for strain-resolution analyses in gut-retina axis research.

4.4 Understudied p.Actinobacteria and p.Verrucomicrobia in the AMD field

The p.Actinobacteria and p.Verrucomicrobia have received comparatively less attention in AMD research, with scant literature beyond a single report indicating an increased abundance of Actinomycetaceae and Actinomyces in the nasal and oral microbial communities of wet AMD patients [51]. Our study now reveals their distinct pathogenic contributions: p.Actinobacteria and its constituent taxa exhibit robust associations with macular degeneration (senile) of retina and early AMD, while p.Verrucomicrobia specifically targets the dry AMD form (Figure 2). Further mediation analysis indicated their impacts on AMD through the modulation of key metabolites and immune cell traits (Table S10). These findings underscore the necessity of moving beyond the traditional focus on p.Firmicutes and p.Bacteroidetes to less-studied phyla in future AMD studies.

This integrative MR analysis provides robust genetic evidence predicting potential causal links between specific GM taxa and the AMD course, complementing current research gaps in the 'GM-AMD' area. However, MR findings should be cautiously interpreted as theoretical evidence predicting causal inference clues rather than definitive empirical conclusions. At present, empirical evidence in this field is scarce, with no large-scale, observational, or longitudinal cohort studies available to validate these predicted associations. Future research should prioritize well-powered prospective cohort studies or controlled clinical interventions targeting candidate GM taxa identified here, and ideally integrate with multi-omics profiling and functional experiments (e.g., germ-free animal models, faecal microbiota transplantation, targeted metabolic interventions, and immune profiling), which will be essential to confirm our MR causality, elucidate underlying mechanisms, and assess translational feasibility in AMD prevention and treatment.

4.5 Strengths and Limitations

The existing body of literature concerning GM-AMD encounters multiple methodological defects in addressing causal AMD-associated GM taxa and investigating their comprehensive impacts throughout the disease course, hindering further mechanism research. The present study utilized an integrated MR framework with intricate design, complementing these critical research gaps from a genetic perspective and surpassing the current literature in at least 5 ways: a) The Dutch Microbiome Project (DMP) provides a shotgun metagenomic sequencing of faecal samples, which enables GWAS data of GM identification to the species level. Precise identification of specific GM taxa is pivotal to future mechanism research. b) We leveraged a diverse array of GWAS datasets of AMD encompassing the disease trajectory. The two-sample MR design enables us to investigate causal impacts from GM exposure to various AMD cohorts representing different AMD stages/subtypes. Consistent results across various cohorts are particularly noteworthy, which can also enhance the genetic prediction power. c) The majority of previous studies in this field are limited to sequencing reports of GM abundance alterations in AMD conditions, where abundance change may not be directly interpreted as the biological function of GM to AMD. The MR analysis assumes the linearity in causality to predict the GM's biological impacts on AMD. d) The mediating role of circulating metabolites was also predicted through robust mediation analysis of MVMR. Causal 'GM-metabolite-AMD' pathways outlined in the present study enhance the investigation of the biological functions of GM in AMD. e) The Bidirectional MR approach raised the innovative proposal of a disease-microbiome feedback loop as a pivotal discovery for the first time. Additionally, we filtered causal results a) with no heterogeneity nor pleiotropy; b) the IVW results reached a significance threshold of P < 0.05; c) the direction of the correlation coefficients remained consistent across all 4 MR modes evaluating causality. We believe such a strict analytic framework ensures the robustness of our MR results.

Meanwhile, several limitations merit consideration. First, the GWAS data were derived almost exclusively from European ancestry. While this homogeneous design reduces the risk of population stratification bias and strengthens internal validity in MR analyses, it limits the direct generalisability of our findings to other ancestral groups. Given documented ethnic variation in AMD prevalence, genetic architecture, and GM composition, future replication in ancestrally diverse cohorts or multi-ancestry MR frameworks will be important to assess both shared and ancestry-specific causal pathways. Second, for certain GM taxa, the limited statistical power of current microbiome GWASs necessitated the use of a relaxed genome-wide significance threshold (p < 1×10⁻⁵) to ensure at least 3-5 independent SNPs for robust estimation. While this approach is supported and accepted by precedents in this field [26-28], and we followed a restricted selection of SNPs with F-statistics > 10, applied stringent LD clumping, and conducted multiple sensitivity analyses, the potential for weak instrument bias and residual horizontal pleiotropy may not be completely ignored. Third, MR findings should be cautiously interpreted as theoretical evidence-predicting causal inference clues rather than definitive empirical conclusions. Future studies integrating large-scale multi-ancestry cohorts, high-resolution metagenomics, longitudinal observational follow-up, and functional experiments will be essential to validate genetically predicted causality and enhance the translational potential of our MR findings.

5. Conclusions

This study marks a pioneering effort in identifying causal AMD-associated GM taxa across the entire disease trajectory, offering unprecedented insights into a longitudinal causality-robust GM-AMD association mapping and stage-specific GM signature for diverse AMD stages/subtypes. Bidirectional results complement the traditional unidirectional "gut-to-retina" paradigm and suggest a self-perpetuating AMD-microbiome feedback loop. Further mediation analyses unravelled potential mechanisms linking GM to AMD through circulating metabolites and immune cell traits, shedding light on pathways that could guide future mechanistic research.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary tables.

Acknowledgements

Funding

The present study received funding from the Program for Research-oriented Physician of Shanghai Tenth People's Hospital (YJXYS-C-003), College-level Project Fund of Shanghai Sixth People's Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine (Grant No. ynts202213), and the Shanghai Municipal Health Commission Research Project (20234Y0079). Nevertheless, the sponsors or funding organizations had no role in the study design or concept; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, Q.P., X.S., and L.L.; methodology & software, X.Y.; validation & formal analysis, Z.W. and C.H.; investigation, J.D.; data curation, X.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Z. and J.D.; supervision, C.H. Revision (including additional formal analysis, response, and revised draft), X.L., J.C., and X.J. Y.Z., Z.W., C.H., and X.Y. contributed equally to this research and should be considered equivalent authors. X.L., X.S., Q.P., and L.L. should be regarded as corresponding authors.

Ethics Committee Approval and Patient Consent

This study utilised de-identified public summary-level data, which is publicly available and can be downloaded free of charge. The data and related information are permitted unrestricted reuse under an open license. The GWASs used in this study were all approved by their respective institutional ethics committees, and consent for publication was obtained. This study is part of the research registered under the ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT05873348, with the registration date of May 23, 2023. The ethics committee from Shanghai Tenth People's Hospital, Tongji University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China, also reviewed the current research proposal with permission.

Data Availability

The summary statistics in this study can be found in online repositories: https://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk/ and https://www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas/downloads/summary-statistics (last access date: 2024/9). Accession number(s) can be found in Table 1.

This work originally focused on the mediatory effects of circulating metabolites solely and was requested to add alternative mediatory candidates during revision, including immune cell traits and inflammatory proteins. As such, a portion of the methodological framework and descriptive content in this article partially overlaps with related studies recently published by our research team [52, 53], as part of an integrated series of investigations.

Competing Interests

The authors have declared that no competing interest exists.

References

1. Klein R, Klein BE, Knudtson MD, Meuer SM, Swift M, Gangnon RE. Fifteen-year cumulative incidence of age-related macular degeneration: the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:253-62

2. Wong JHC, Ma JYW, Jobling AI, Brandli A, Greferath U, Fletcher EL. et al. Exploring the pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration: A review of the interplay between retinal pigment epithelium dysfunction and the innate immune system. Front Neurosci. 2022;16:1009599

3. Floyd JL, Grant MB. The Gut-Eye Axis: Lessons Learned from Murine Models. Ophthalmol Ther. 2020;9:499-513

4. Napolitano P, Filippelli M, Davinelli S, Bartollino S, dell'Omo R, Costagliola C. Influence of gut microbiota on eye diseases: an overview. Ann Med. 2021;53:750-61

5. Grant MB, Bernstein PS, Boesze-Battaglia K, Chew E, Curcio CA, Kenney MC. et al. Inside out: Relations between the microbiome, nutrition, and eye health. Exp Eye Res. 2022;224:109216

6. Xiao J, Zhang JY, Luo W, He PC, Skondra D. The Emerging Role of Gut Microbiota in Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Am J Pathol. 2023;193:1627-37

7. Armstrong RA, Mousavi M. Overview of Risk Factors for Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD). J Stem Cells. 2015;10:171-91

8. Zhang Y, Wang T, Wan Z, Bai J, Xue Y, Dai R. et al. Alterations of the intestinal microbiota in age-related macular degeneration. Front Microbiol. 2023;14:1069325

9. Skrivankova VW, Richmond RC, Woolf BAR, Yarmolinsky J, Davies NM, Swanson SA. et al. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology Using Mendelian Randomization: The STROBE-MR Statement. Jama. 2021;326:1614-21

10. Seddon JM, Cote J, Page WF, Aggen SH, Neale MC. The US twin study of age-related macular degeneration: relative roles of genetic and environmental influences. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:321-7

11. Meyers SM, Greene T, Gutman FA. A twin study of age-related macular degeneration. Am J Ophthalmol. 1995;120:757-66

12. Luo L, Harmon J, Yang X, Chen H, Patel S, Mineau G. et al. Familial aggregation of age-related macular degeneration in the Utah population. Vision Res. 2008;48:494-500

13. Assink JJ, Klaver CC, Houwing-Duistermaat JJ, Wolfs RC, van Duijn CM, Hofman A. et al. Heterogeneity of the genetic risk in age-related macular disease: a population-based familial risk study. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:482-7

14. Klaver CC, Kliffen M, van Duijn CM, Hofman A, Cruts M, Grobbee DE. et al. Genetic association of apolipoprotein E with age-related macular degeneration. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;63:200-6

15. Nguyen J, Brantley MA Jr, Schwartz SG. Genetics and Age-Related Macular Degeneration: A Practical Review for Clinicians. Front Biosci (Schol Ed). 2024;16:3

16. Nakanishi H, Yamashiro K, Yamada R, Gotoh N, Hayashi H, Nakata I. et al. Joint effect of cigarette smoking and CFH and LOC387715/HTRA1 polymorphisms on polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:6183-7

17. Schmidt S, Hauser MA, Scott WK, Postel EA, Agarwal A, Gallins P. et al. Cigarette smoking strongly modifies the association of LOC387715 and age-related macular degeneration. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;78:852-64

18. Hogg RE, Dimitrov PN, Dirani M, Varsamidis M, Chamberlain MD, Baird PN. et al. Gene-environment interactions and aging visual function: a classical twin study. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:263-9

19. Lopera-Maya EA, Kurilshikov A, van der Graaf A, Hu S, Andreu-Sánchez S, Chen L. et al. Effect of host genetics on the gut microbiome in 7,738 participants of the Dutch Microbiome Project. Nat Genet. 2022;54:143-51

20. Winkler TW, Grassmann F, Brandl C, Kiel C, Günther F, Strunz T. et al. Genome-wide association meta-analysis for early age-related macular degeneration highlights novel loci and insights for advanced disease. BMC Med Genomics. 2020;13:120

21. Yan Q, Ding Y, Liu Y, Sun T, Fritsche LG, Clemons T. et al. Genome-wide analysis of disease progression in age-related macular degeneration. Hum Mol Genet. 2018;27:929-40

22. Kurki MI, Karjalainen J, Palta P, Sipilä TP, Kristiansson K, Donner KM. et al. FinnGen provides genetic insights from a well-phenotyped isolated population. Nature. 2023;613:508-18

23. Chen Y, Lu T, Pettersson-Kymmer U, Stewart ID, Butler-Laporte G, Nakanishi T. et al. Genomic atlas of the plasma metabolome prioritizes metabolites implicated in human diseases. Nat Genet. 2023;55:44-53

24. Zhao JH, Stacey D, Eriksson N, Macdonald-Dunlop E, Hedman Å K, Kalnapenkis A. et al. Genetics of circulating inflammatory proteins identifies drivers of immune-mediated disease risk and therapeutic targets. Nat Immunol. 2023;24:1540-51

25. Orrù V, Steri M, Sidore C, Marongiu M, Serra V, Olla S. et al. Complex genetic signatures in immune cells underlie autoimmunity and inform therapy. Nat Genet. 2020;52:1036-45

26. Fu L, Baranova A, Cao H, Zhang F. Gut microbiome links obesity to type 2 diabetes: insights from Mendelian randomization. BMC Microbiol. 2025;25:253

27. Li X, Xu B, Yang H, Zhu Z. Gut Microbiota, Human Blood Metabolites, and Esophageal Cancer: A Mendelian Randomization Study. Genes (Basel). 2024 15

28. Chen J, Wang X, Yang J, Huang J, Xie M, Su Z. et al. Association between gut microbiota and central retinal artery occlusion: A two-sample Mendelian randomization study. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2024;72:S801-s8

29. Bowden J, Davey Smith G, Burgess S. Mendelian randomization with invalid instruments: effect estimation and bias detection through Egger regression. Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44:512-25

30. Burgess S, Daniel RM, Butterworth AS, Thompson SG. Network Mendelian randomization: using genetic variants as instrumental variables to investigate mediation in causal pathways. Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44:484-95

31. Sanderson E. Multivariable Mendelian Randomization and Mediation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2021 11

32. Carter AR, Sanderson E, Hammerton G, Richmond RC, Davey Smith G, Heron J. et al. Mendelian randomisation for mediation analysis: current methods and challenges for implementation. Eur J Epidemiol. 2021;36:465-78

33. Pedersen C, Ijaz UZ, Gallagher E, Horton F, Ellis RJ, Jaiyeola E. et al. Fecal Enterobacteriales enrichment is associated with increased in vivo intestinal permeability in humans. Physiol Rep. 2018;6:e13649

34. Belete GT, Zhou L, Li KK, So PK, Do CW, Lam TC. Metabolomics studies in common multifactorial eye disorders: a review of biomarker discovery for age-related macular degeneration, glaucoma, diabetic retinopathy and myopia. Front Mol Biosci. 2024;11:1403844

35. Zhang Y, Jia H, Jin Y, Liu N, Chen J, Yang Y. et al. Glycine Attenuates LPS-Induced Apoptosis and Inflammatory Cell Infiltration in Mouse Liver. J Nutr. 2020;150:1116-25

36. Egger F, Jakab M, Fuchs J, Oberascher K, Brachtl G, Ritter M. et al. Effect of Glycine on BV-2 Microglial Cells Treated with Interferon-γ and Lipopolysaccharide. Int J Mol Sci. 2020 21

37. Rowan S, Jiang S, Korem T, Szymanski J, Chang ML, Szelog J. et al. Involvement of a gut-retina axis in protection against dietary glycemia-induced age-related macular degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114:E4472-e81

38. Johnson DA, Fields C, Fallon A, Fitzgerald ME, Viar MJ, Johnson LR. Polyamine-dependent migration of retinal pigment epithelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:1228-33

39. Yanagihara N, Moriwaki M, Shiraki K, Miki T, Otani S. The involvement of polyamines in the proliferation of cultured retinal pigment epithelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1996;37:1975-83

40. Du J, Zhu S, Lim RR, Chao JR. Proline metabolism and transport in retinal health and disease. Amino Acids. 2021;53:1789-806

41. Zhu S, Xu R, Engel AL, Wang Y, McNeel R, Hurley JB. et al. Proline provides a nitrogen source in the retinal pigment epithelium to synthesize and export amino acids for the neural retina. J Biol Chem. 2023;299:105275

42. Yam M, Engel AL, Wang Y, Zhu S, Hauer A, Zhang R. et al. Proline mediates metabolic communication between retinal pigment epithelial cells and the retina. J Biol Chem. 2019;294:10278-89

43. Chen M, Wang Y, Dalal R, Du J, Vollrath D. Alternative oxidase blunts pseudohypoxia and photoreceptor degeneration due to RPE mitochondrial dysfunction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2024;121:e2402384121

44. Riazati N, Kable ME, Newman JW, Adkins Y, Freytag T, Jiang X. et al. Associations of microbial and indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase-derived tryptophan metabolites with immune activation in healthy adults. Front Immunol. 2022;13:917966

45. Li C, Lu P. Association of Gut Microbiota with Age-Related Macular Degeneration and Glaucoma: A Bidirectional Mendelian Randomization Study. Nutrients. 2023 15

46. El Hage R, Hernandez-Sanabria E, Calatayud Arroyo M, Props R, Van de Wiele T. Propionate-Producing Consortium Restores Antibiotic-Induced Dysbiosis in a Dynamic in vitro Model of the Human Intestinal Microbial Ecosystem. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:1206

47. Xue W, Peng P, Wen X, Meng H, Qin Y, Deng T. et al. Metagenomic Sequencing Analysis Identifies Cross-Cohort Gut Microbial Signatures Associated with Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2023;64:11

48. Zinkernagel MS, Zysset-Burri DC, Keller I, Berger LE, Leichtle AB, Largiadèr CR. et al. Association of the Intestinal Microbiome with the Development of Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Sci Rep. 2017;7:40826

49. Mao D, Tao B, Sheng S, Jin H, Chen W, Gao H. et al. Causal Effects of Gut Microbiota on Age-Related Macular Degeneration: A Mendelian Randomization Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2023;64:32

50. Liu K, Zou J, Yuan R, Fan H, Hu H, Cheng Y. et al. Exploring the Effect of the Gut Microbiome on the Risk of Age-Related Macular Degeneration from the Perspective of Causality. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2023;64:22

51. Rullo J, Far PM, Quinn M, Sharma N, Bae S, Irrcher I. et al. Local oral and nasal microbiome diversity in age-related macular degeneration. Sci Rep. 2020;10:3862

52. Zhou Y, Wang Z, Huang C, Yu X, Cai X, Zhao D. et al. Genetically predicted causal links between gut microbiota and biological aging phenotypes in age-related macular degeneration. Biogerontology. 2025;26:191

53. Zhou Y, Liu J, Wang Z, Huang C, Wang Q, Yu X. et al. Biological aging phenotypes mediate gut microbiota effects on age-related macular degeneration subtype progression: genetic causality by mendelian randomization and mediation analysis. AMB Express. 2025;15:167

Author contact

![]() Corresponding authors: Xinmin Lu, MD, xinmin.lucom, Xudong Song, MD, PhD, drxdsongcom, Long Li, MD, long_liedu.cn, Qing Peng, MD, drpengqingcom.

Corresponding authors: Xinmin Lu, MD, xinmin.lucom, Xudong Song, MD, PhD, drxdsongcom, Long Li, MD, long_liedu.cn, Qing Peng, MD, drpengqingcom.

Global reach, higher impact

Global reach, higher impact