Impact Factor

ISSN: 1449-1907

Int J Med Sci 2026; 23(2):566-575. doi:10.7150/ijms.121837 This issue Cite

Research Paper

The Relationship Between Thyroid Function or Subclinical Hypothyroidism in Early Pregnancy and Risk of Low Birth Weight and Small for Gestational Age of the Offspring: A Multicentre Prospective Cohort Study

1. Department of Central Laboratory, Beijing Obstetrics and Gynecology Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing Maternal and Child Health Care Hospital, Beijing 100026, China.

2. Department of Obstetrics, Beijing Obstetrics and Gynecology Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing Maternal and Child Health Care Hospital, Beijing 100026, China.

3. Nuffield Department of Women's and Reproductive Health, University of Oxford, The Women's Centre, John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, UK.

Received 2025-7-16; Accepted 2025-12-15; Published 2026-1-1

Abstract

Objective: To examine how maternal thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), free thyroxine (FT4) and thyroid peroxidase antibody (TPOAb) status in early pregnancy relate to low birth weight (LBW) or small for gestational age (SGA) outcomes.

Methods: This prospective cohort analysis utilized data from 125,365 singleton pregnancies in the China Birth Cohort Study (2018-2022), with participants enrolled at 6-13+6weeks gestation from 9 tertiary hospitals. The potential associations among maternal thyroid functional indices, spectrum of thyroid dysfunction, and adverse neonatal outcomes (LBW/SGA) were statistically evaluated employing generalized linear mixed modeling techniques. Besides, to verify the consistency of these findings, we conducted comprehensive subgroup analyses across multiple demographic and clinical strata.

Results: Among the final 86,015 eligible participants, LBW and SGA occurred in 3.18% (n=2,731) and 3.56% (n=3,060), respectively. After adjusting for maternal and neonatal characteristics, analyses revealed significant negative associations between circulating maternal thyroid hormone levels and offspring birth weight measurements (per 1 mIU/L increase in TSH: β = -5.62, 95% CI: -7.29 to -3.95, P < 0.001; per 1 pmol/L increase in FT4: β = -1.43, 95% CI: -2.21 to -0.65, P < 0.001). First-trimester subclinical hypothyroidism (SCH) was associated with increased risks of both LBW (aOR = 1.29, 95% CI: 1.04-1.59; P = 0.021) and SGA (aOR = 1.18, 95% CI:1.01-1.38; P = 0.037). Women in the highest TSH quintile had 20% higher LBW risk (aOR = 1.20, 95% CI: 1.02-1.41; P = 0.028) and 16% higher SGA risk compared to the lowest quintile (aOR = 1.16, 95% CI: 1.03-1.30; P = 0.012). The associations of TSH and FT4 with LBW and SGA were consistent across all subgroups.

Conclusions: Elevated maternal TSH, elevated FT4 (even within high-normal ranges), and SCH in early pregnancy serve as significant risk indicators for LBW and SGA.

Keywords: thyroid function, thyroid-stimulating hormone, free thyroxine, low birth weight, small for gestational age

Introduction

In pregnancy, thyroid hormones are essential as they affect placental function, fetal development, and the expression of neuropeptides associated with parturition [1]. Thyroid pathologies—are among the most prevalent endocrine conditions in pregnancy and include subclinical hypothyroidism (SCH) —the most common thyroid dysfunction affecting 3.5% of all women [2], hyperthyroidism, and hypothyroidism. Abnormal maternal thyroid status may contribute to several adverse perinatal outcomes, and has been associated with gestational diabetes, hypertensive disorders, miscarriage, preterm birth, neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission, low APGAR scores, low birth weight (LBW) and small for gestational age (SGA) [3-9]. Both LBW and SGA— pose a significant global health burden as they collectively affect an estimated 20 million neonates annually [10] and are linked to elevated likelihood of late-onset noncommunicable conditions [11-13].

Nevertheless, the potential link between maternal thyroid abnormalities and compromised fetal growth outcomes (LBW/SGA) has yet to reach consensus in the research community. Some studies suggest that elevated maternal thyrotropin (TSH) and free thyroxine (FT4) levels are inversely correlated with birth weight, so that higher FT4 in early pregnancy increases the likelihood of LBW [11, 14]. Conversely, other studies report no significant association [15, 16]. Similarly, first-trimester TSH levels between 4-10mIU/L were associated with significantly increased risks of SGA [17] in some but not other studies [18]. This existing evidence is limited by small sample sizes and methodological inconsistencies in defining thyroid reference intervals [19].

To address these gaps in knowledge which are in part due to small study sizes, methodological inconsistencies and varying definitions of thyroid reference intervals, this large population-based cohort investigation was embedded within the China Birth Cohort Study (CBCS) [20]. The core objective of this study is to systematically examine the nature and magnitude of correlations between maternal thyroid biomarker profiles during the specific gestational window of 6 to 13+6 weeks—specifically, TSH concentrations, FT4 levels, and thyroid peroxidase antibody (TPOAb) positivity—and adverse birth outcomes in offspring, including LBW and SGA. This investigation seeks to provide a foundational evidence base for research exploring the relationship between thyroid function management during pregnancy and fetal health outcomes.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

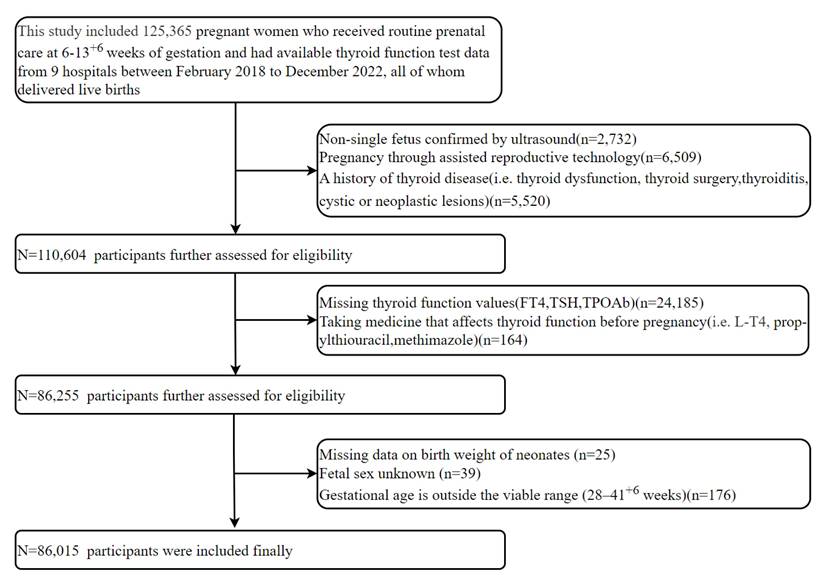

This multicentre prospective cohort study utilized data from the CBCS [20], analyzing 125,365 pregnant women who received first-trimester prenatal care (starting at a gestational age 6-13+6 weeks) across 9 hospitals between February 2018 and December 2022. All participants underwent first-trimester thyroid function testing and subsequently delivered live-born singletons. We excluded: (1) ultrasound-confirmed non-singleton pregnancy in the first trimester; (2) Pregnancies conceived through assisted reproductive technology (ART), such as in vitro fertilization, intracytoplasmic sperm injection, or embryo transfer; (3) Prior diagnoses of thyroid conditions, encompassing pre-pregnancy thyroid dysfunction, surgical removal of the thyroid, thyroiditis, as well as cystic or neoplastic thyroid lesions; (4) Missing thyroid function values(FT4, TSH, TPOAb); (5)Preconception intake of thyroid-modulating drugs (i.e. L-T4, propylthiouracil, methimazole); (6) Missing data on neonatal birth weight; (7) Unknown fetal sex; (8) Gestational age at birth outside 28-41+6 weeks. After screening and eligibility assessment, 86,015 pregnant women were enrolled in this investigation. Based on prior evidence showing an odds ratio (OR) of 1.16-1.24[11, 21] between thyroid function and SGA, and a background SGA prevalence of 3.56% in our population, a sample size of 9,448-19,847 was estimated to provide sufficient power (α=0.05, δ=0.10). The research protocol was approved by the institutional ethics committee (Beijing Obstetrics and Gynecology Hospital, Capital Medical University; Approval No. 2018-KY-003-02), and written informed consent was properly executed by each participant before any study procedures.

Data collection

Through standardized questionnaire administration, demographic profiles were established [20]. Baseline data included maternal age, pre-pregnancy BMI, ethnic group, smoking, alcohol consumption status and obstetric history. Educational attainment was classified into three levels: primary school or lower, high school or lower, and college or above. Annual household income was stratified as < 100,000 CNY, 100,000-400,000 CNY, or > 400,000 CNY. Binary variables (yes/no) were used to document pre-existing medical conditions (hypertension and diabetes) and health behaviours (smoking and alcohol consumption). Additionally, we collected data on pre-pregnancy thyroid disease history, thyroid-related medication status, gestational weeks at parturition and neonatal sex. Through digital means, all records are consistently gathered and kept up to date.

Blood collection occurred at the initial prenatal visit at 6-13+6 weeks of gestation, following fasting for 8-10h overnight. Serum levels of TSH, FT4, and TPOAb were measured using an electrochemiluminescence immunoassay system. The manufacturer's recommended threshold was applied, with TPOAb concentrations ≥ 60 IU/L considered positive. International consensus (e.g., ATA guidelines) recommends the adoption of trimester-specific reference ranges derived from healthy pregnant women who have sufficient iodine levels, no thyroid dysfunction, and negative TPOAb status [22]. All participants were recruited from regions that have implemented universal salt iodization since 1995, where the general population maintains replete iodine nutrition without widespread deficiency or excess. Following the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria (see Methods), we further excluded individuals who tested positive for TPOAb. Euthyroidism was defined as serum TSH and FT4 levels falling within the 5th-95th percentile ranges (TSH: 0.13-3.60 mU/L; FT4: 11.35-19.62 pmol/L). This approach accounts for potential sample storage effects and is consistent with reference ranges established in previous studies [19, 23]. Thyroid dysfunction was classified as overt hyperthyroidism (TSH < 5.0th percentile with FT4 > 95.0th percentile), overt hypothyroidism (TSH > 95.0th percentile with FT4 < 5.0th percentile), subclinical hyperthyroidism (TSH < 5.0th percentile with normal FT4), subclinical hypothyroidism (TSH > 95.0th percentile with normal FT4), and isolated hypothyroxinemia (FT4 < 5.0th percentile with normal TSH). All classifications were based on the established reference ranges, with normal function defined as both TSH and FT4 falling within the 5.0th-95.0th percentiles.

LBW was defined as birth weight less than 2,500g [24], SGA was classified as a birth weight below the 10th percentile for sex and gestational age based on INTERGROWTH-21st standards [25].

Statistical analysis

Data were presented as mean ± SD (normally distributed), median (IQR) (non-normal), or frequencies (%) (categorical). Group comparisons (LBW vs. non-LBW; SGA vs. non-SGA) used t-tests, Mann-Whitney U tests, or χ²/Fisher's exact tests as appropriate. We used linear regression to assess the relationship between maternal thyroid function and offspring birth weight, while employing multivariate logistic regression to evaluate the associations of maternal thyroid hormone levels and diseases with the risks of LBW and SGA. A restricted cubic spline model was further applied to characterize the exposure-response relationships more flexibly. For these analyses, TSH and FT4 were treated as continuous variables and also categorized into quintiles to assess potential linear trends.

To examine the consistency of the links between maternal thyroid hormone levels (TSH/FT4) and poor neonatal outcomes (LBW and SGA), we conducted stratified analyses across clinically relevant subgroups. Maternal age (< 35 vs. ≥ 35 years), pre-pregnancy BMI (< 25 vs. ≥ 25 kg/m²), parity (nulliparous vs. multiparous), neonatal sex (male vs. female), and TPOAb positive (yes vs.no) were considered as potential effect modifiers. Interaction P-values were computed to assess whether these variables significantly influenced the observed relationships.

Analyses were performed using SPSS 25.0 and RStudio4.0.3.

Results

Study population enrollment and exclusion

After applying exclusion criteria to the initial 125,365 women, 86,015 were included in the final analysis (Figure 1), with exclusions as follows: non-singleton pregnancy (n = 2,732); conception by ART (n = 6,509); preexisting thyroid conditions (n = 5,520); missing thyroid function values (n = 24,185); use of thyroid medications (n=164); missing neonatal birth weight data (n = 25); unknown fetal sex (n = 39); and non-viable gestational age (n = 176). This rigorous process aimed to minimize bias and enhance internal validity.

Baseline characteristics of the study population

The study cohort included 86,015 eligible participants, comprising 2,731 LBW cases (3.18%) and 3,060 SGA cases (3.56%), (Table 1). Table 1 demonstrates statistically significant disparities in maternal age, pre-conception BMI, annual family income, gestational age at delivery, and TSH levels between LBW and non-LBW groups, as well as between SGA and non-SGA groups. Mothers of LBW infants had higher rates of pre-existing hypertension (1.6% vs. 0.3%, P < 0.001), lower educational attainment (high school or below: 12.9% vs. 10.3%, P < 0.001). Furthermore, a higher proportion of LBW infants were female (52.5% vs. 48.3%, P < 0.001). For SGA, significant associations were found with maternal alcohol consumption (3.3% vs. 4.0%, P = 0.031), multiparity (65.9% vs. 54.4%, P < 0.001), and TPOAb positivity (7.2% vs. 8.2%, P = 0.039). However, no meaningful linkages were observed between LBW/SGA and maternal race, maternal smoking, previous diabetes or FT4 levels.

Flow chart of study participants selection.

Association between first-trimester thyroid hormone levels and neonatal birth weight

As shown in Table 2, crude analyses demonstrated that each 1 mIU/L increase in maternal TSH was inversely associated with birth weight (β = -5.00 g, 95% CI: -7.01 to -2.99, P < 0.001). A similar inverse association was observed for each 1 pmol/L increase in maternal FT4 (β = -3.20 g, 95% CI: -4.15 to -2.26, P < 0.001). These inverse relationships remained significant after adjusting for maternal age, pre-conception BMI, maternal smoking/drinking behaviors, educational attainment, annual family income, parity, pre-existing hypertension or diabetes, gestational age at delivery, neonatal sex, TPOAb positive and regional clustering effects. Importantly, the adjusted effect sizes remained consistent (per 1 mIU/L increase in TSH: β = -5.62, 95% CI: -7.29 to -3.95, P < 0.001; per 1 pmol/L increase in FT4: β = -1.43, 95% CI: -2.21 to -0.65, P < 0.001). In contrast, regardless of adjustment for covariates, maternal TPOAb status demonstrated no statistically significant effect on infant birth weight.

Correlation between early-pregnancy maternal thyroid hormone levels, thyroid disorders and the risk of LBW or SGA

Adjusted models revealed a significant link between maternal thyroid status and neonatal complications. As shown in Table 3, each 1-unit increase in FT4 was associated with a 2% higher risk of LBW (aOR 1.02, 95% CI 1.00-1.03, P = 0.033), while each 1-unit TSH increase was associated with a 2% greater SGA risk (aOR 1.02, 95% CI 1.01-1.04, P = 0.012), after adjustment for confounders. Subclinical hypothyroidism significantly increased the odds of both LBW (aOR 1.29, 95% CI 1.04-1.59, P = 0.021) and SGA (aOR 1.18, 95% CI 1.01-1.38, P = 0.037) compared to euthyroidism. TPOAb positivity showed no significant associations in any model.

Stratified analysis of LBW/SGA risk by maternal TSH and FT4 Levels

As can be seen in Table 4, in the quintile analysis of maternal FT4 levels, no individual quintile was associated with a significantly increased risk of LBW compared with the lowest quintile after full adjustment for confounders. However, a statistically significant linear trend was observed across the FT4 quintiles (P for trend = 0.033). For TSH levels, women in the highest quintile had a modestly increased risk of both SGA and LBW compared with those in the lowest quintile. The adjusted ORs were 1.16 (95% CI: 1.03-1.30; P = 0.012) for SGA and 1.20 (95% CI: 1.02-1.41; P = 0.028) for LBW, representing 16% and 20% increased risks, respectively. Additionally, a significant dose-response relationship was evident for SGA, as indicated by a significant trend across the quintiles (P for trend = 0.012).

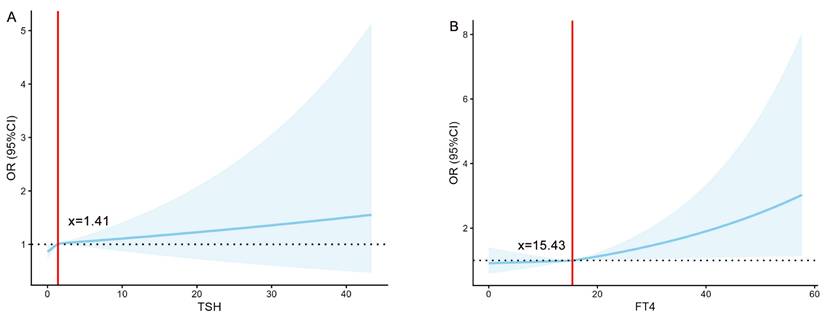

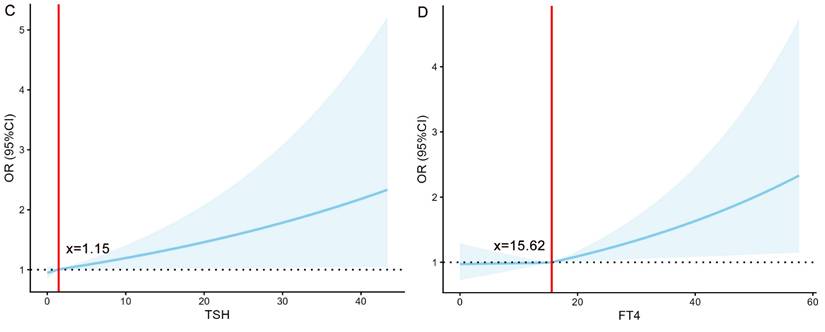

To quantify the associations of TSH and FT4 with the risks of LBW and SGA, this study employed restricted cubic spline models for analysis (Figure 2). The analysis revealed significant nonlinear associations between TSH and SGA risk, as well as between FT4 and LBW risk (all P < 0.001). Specifically, the risks remained stable below specific thresholds but increased markedly once these thresholds were exceeded, indicating that elevated levels of both FT4 and TSH serve as important warning signals for an increased risk of both LBW and SGA.

General characteristics among the study population

| Demographics | Total (n=86,015) | LBW (n=2731) | Non-LBW (n=83,284) | SGA (n=3060) | Non-SGA (n=82,955) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age(years), n (%) a, b | 86,015 | ||||

| <35 | 74,397 (86.5) | 2250(82.4) | 72,147 (86.6) | 2756(90.1) | 71,641 (86.4) |

| ≥35 | 11,618(13.5) | 481(17.6) | 11,137(13.4) | 304(9.9) | 11,314 (13.6) |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI, n (%) a, b | |||||

| <25 | 75,637 (87.9) | 2318 (84.9) | 73,319(88.0) | 2782 (90.9) | 72,855(87.8) |

| ≥25 | 10,378 (12.1) | 413(15.1) | 9965(12.0) | 278(9.1) | 10,100(12.2) |

| Ethnic, n (%) | |||||

| Han | 81,729(95.0) | 2589(94.8) | 79,140(95.0) | 2908 (95.0) | 78,821(95.0) |

| Others | 4286 (5.0) | 142(5.2) | 4144 (5.0) | 152(5.0) | 4134(5.0) |

| Smoking, n (%) | |||||

| Yes | 170(0.2) | 8(0.3) | 162(0.2) | 10(0.3) | 160(0.2) |

| No | 85,845 (99.8) | 2723 (99.7) | 83,122(99.8) | 3050 (99.7) | 82,795(99.8) |

| Drinking, n (%) b | |||||

| Yes | 3456(4.0) | 102(3.7) | 3354(4.0) | 100(3.3) | 3356(4.0) |

| No | 82,559(96.0) | 2629(96.3) | 79,930 (96.0) | 2960(96.7) | 79,599 (96.0) |

| Parity, n (%) b | |||||

| Nullipara | 38,896(45.2) | 1218 (44.6) | 37,678(45.2) | 1043 (34.1) | 37,853 (45.6) |

| Multipara | 47,119 (54.8) | 1513(55.4) | 45,606 (54.8) | 2017(65.9) | 45,102 (54.4) |

| Maternal education, n (%) a | |||||

| Primary school or lower | 105(0.1) | 5 (0.2) | 100 (0.1) | 5 (0.2) | 100 (0.1) |

| High school or lower | 8791(10.2) | 348 (12.7) | 8443(10.2) | 305 (10.0) | 8486 (10.2) |

| College or above | 77,119(89.7) | 2378 (87.1) | 74,741(89.7) | 2750 (89.8) | 74,369(89.7) |

| Household annual income, n (%) a, b | |||||

| <100,000,CNY | 18,218(21.2) | 681(25.0) | 17,537 (21.1) | 770 (25.2) | 17,488 (21.0) |

| 100,000, CNY-400,000, CNY | 54,560(63.4) | 1670 (61.1) | 52,890(63.5) | 1881(61.5) | 52,679(63.5) |

| >400,000, CNY | 13,237 (15.4) | 380 (13.9) | 12,857(15.4) | 409 (13.3) | 12,828(15.5) |

| Pre-hypertension disease, n (%) a | |||||

| Yes | 259 (0.3) | 45(1.6) | 214 (0.3) | 12(0.4) | 247 (0.3) |

| No | 85,756 (99.7) | 2686(98.4) | 83,070(99.7) | 3048 (99.6) | 82,708 (99.7) |

| Previous diabetes, n (%) | |||||

| Yes | 271(0.3) | 14 (0.5) | 257 (0.3) | 6 (0.2) | 265 (0.3) |

| No | 85,744(99.7) | 2717 (99.5) | 83,027 (99.7) | 3054(99.8) | 82,690 (99.7) |

| Gestational age at delivery, mean ± SD a, b | 38.86±1.44 | 34.97±2.69 | 38.98±1.18 | 38.74±1.62 | 38.86±1.43 |

| Neonatal gender, n (%) a | |||||

| Male | 44,354(51.6) | 1298 (47.5) | 43,056(51.7) | 1583(51.7) | 42,771(51.6) |

| Female | 41,661 (48.4) | 1433(52.5) | 40,228(48.3) | 1477(48.3) | 40,184(48.4) |

| TSH, mU/L, mean ± SD a, b | 1.58±1.50 | 1.68±1.50 | 1.58±1.50 | 1.67±1.70 | 1.58±1.49 |

| FT4, pmol/L, mean ± SD | 15.36±3.18 | 15.43±3.33 | 15.36±3.18 | 15.41±3.54 | 15.36±3.17 |

| TPOAb positive, n (%) b | |||||

| Yes (≥60U/L) | 7050(8.2) | 227 (8.3) | 6823 (8.2) | 220 (7.2) | 6830 (8.2) |

| No (<60U/L) | 78,965 (91.8) | 2504(91.7) | 76,461(91.8) | 2840(92.8) | 76,125(91.8) |

a Significant differences were observed between the LBW and non-LBW groups (P < 0.05)

b Significant differences were observed between the SGA and non-SGA groups (P < 0.05)

Abbreviation: LBW, low birth weight; SGA, small for gestational age; BMI, body mass index; SD, standard deviation; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone; FT4, free thyroxine; TPOAb, thyroid peroxidase antibody.

Association of thyroid function in early pregnancy with neonatal birth weight

| Crude Modelβ (95% CI) | Adjusted Modelβ (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| neonatal birth weight | ||

| TSH | -5.00 (-7.01, -2.99) | -5.62(-7.29, -3.95) |

| FT4 | -3.20(-4.15, -2.26) | -1.43(-2.21, -0.65) |

| TPOAb positive | -2.70(-13.67, 8.26) | 4.16(-13.20, 4.88) |

P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Crude Modelβ: Unadjusted modelβ.

Adjusted Modelβ: adjusted for maternal age, pre-pregnancy BMI, Smoking, Drinking, maternal education, household annual income, previous hypertension disease, previous diabetes, gestational age at delivery, neonatal sex, TPOAb positive and regional clustering effects.

Abbreviation: TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone; FT4, free thyroxine; TPOAb, thyroid peroxidase antibody.

The association between maternal thyroid hormone levels and various thyroid disorders during early pregnancy and the risk of LBW or SGA.

| LBW | SGA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted Model a OR (95%CI) | P-value | Adjusted Model b OR (95%CI) | P-value | ||

| TSH | 1.02(1.00- 1.05) | 0.121 | 1.02(1.01- 1.04) | 0.012 | |

| FT4 | 1.02(1.00- 1.03) | 0.033 | 1.01(1.00- 1.02) | 0.046 | |

| TPOAb positive | 0.99(0.83- 1.19) | 0.941 | 0.89(0.77-1.02) | 0.100 | |

| Euthyroidism c | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| Overt hyperthyroidism | 1.06(0.76- 1.48) | 0.732 | 1.21(0.96- 1.54) | 0.108 | |

| Overt hypothyroidism | 1.03(0.50- 2.12) | 0.928 | 0.91(0.54- 1.52) | 0.706 | |

| Subclinical hyperthyroidism | 0.77(0.55- 1.09) | 0.144 | 0.84(0.65- 1.07) | 0.155 | |

| Subclinical hypothyroidism | 1.29(1.04- 1.59) | 0.021 | 1.18(1.01- 1.38) | 0.037 | |

| Isolated hypothyroxinemia | 1.00(0.77- 1.30) | 0.978 | 1.00(0.83- 1.19) | 0.961 | |

P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Adjusted Model a: adjusted for maternal age, pre-pregnancy BMI, maternal education, household annual income, previous hypertension disease, gestational age at delivery, neonatal sex, parity × BMI interactions and regional clustering effects.

Adjusted Model b: adjusted for maternal age, pre-pregnancy BMI, Drinking, parity, household annual income, gestational age at delivery, TPOAb positive, parity × BMI interactions and regional clustering effects.

c Defined as mothers with normal range (5th to 95th percentiles) for TSH and FT4 levels.

Abbreviation: TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone; FT4, free thyroxine; TPOAb, thyroid peroxidase antibody.

Risk of LBW or SGA at different levels of TSH and FT4 in all enrolled women

| LBW | SGA | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| aOR (95%CI) a | P-value | aOR (95%CI) b | P-value | |

| TSH (mIU/L) | ||||

| Q1(≤ 0.62) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Q2(0.63-1.10) | 0.98(0.83- 1.16) | 0.826 | 1.06(0.94- 1.19) | 0.346 |

| Q3(1.11-1.59) | 1.06(0.90- 1.25) | 0.467 | 1.08(0.96- 1.21) | 0.211 |

| Q4(1.60-2.32) | 1.10(0.93-1.29) | 0.255 | 1.03(0.92-1.16) | 0.586 |

| Q5(≥2.33) | 1.20(1.02-1.41) | 0.028 | 1.16(1.03-1.30) | 0.012 |

| P for trend | 0.121 | 0.012 | ||

| FT4 (pmol/L) | ||||

| Q1(≤ 13.39) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Q2(13.40-14.80) | 1.09(0.92-1.29) | 0.303 | 1.01(0.90-1.14) | 0.822 |

| Q3(14.81-15.96) | 1.07(0.91-1.27) | 0.411 | 0.99(0.88-1.12) | 0.917 |

| Q4(15.97-17.35) | 1.16(0.98-1.37) | 0.076 | 1.03(0.91-1.16) | 0.642 |

| Q5(≥17.36) | 1.18(1.00-1.40) | 0.053 | 1.06(0.94-1.20) | 0.332 |

| P for trend | 0.033 | 0.046 | ||

P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

aOR a, Adjusted Model a: adjusted for maternal age, pre-pregnancy BMI, maternal education, household annual income, previous hypertension disease, gestational age at delivery, neonatal sex, parity × BMI interactions and regional clustering effects.

aOR b, Adjusted Model b: adjusted for maternal age, pre-pregnancy BMI, Drinking, parity, household annual income, gestational age at delivery, TPOAb positive, parity × BMI interactions and regional clustering effects.

Abbreviation: LBW, low birth weight; SGA, small for gestational age; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone; FT4, free thyroxine.

The association of TSH (mIU/L) /FT4 (pmol/L) with the risk of LBW/SGA. (A) The relationship between TSH and the risk of LBW. (B) The relationship between FT4 and the risk of LBW. (C) The relationship between TSH and the risk of SGA. (D) The relationship between FT4 and the risk of SGA. FT4, free thyroxine; TSH, thyroid-stimulating Hormone; LBW, low birth weight; SGA, small for gestational age; OR, odds ratio.

Subgroup analysis

Subgroup analyses (stratified by maternal age, pre-pregnancy BMI, parity, fetal sex, and TPOAb positivity) demonstrated that the positive association between elevated TSH (≥ 2.33 mIU/L) and the risks of both LBW and SGA was consistent across all subgroups, with no significant interaction effects observed (Figure S1 and S3). While the association between FT4 and LBW initially appeared stronger in TPOAb-positive women, this difference was no longer significant after false discovery rate (FDR) correction, suggesting a potential false-positive finding (Figure S2). Similarly, the association between FT4 and SGA remained consistent across all subgroups (Figure S4).

Discussion

Our study identified independent dose-response relationships between elevated first-trimester maternal TSH and FT4 levels with reduced neonatal birth weight. Subclinical hypothyroidism was associated with significantly increased risks of both LBW and SGA compared to euthyroidism. Furthermore, the associations of TSH and FT4 with LBW/SGA demonstrated nonlinear threshold effects. Notably, the positive association between elevated TSH (≥ 2.33 mIU/L) and the risks of LBW/SGA remained consistent across all subgroups, underscoring the robustness of this relationship.

This study demonstrates methodological rigor through several key strengths. First, the large multicentre cohort comprising 86,015 pregnant women from 9 hospitals provides robust statistical power while minimizing selection bias. Second, standardized thyroid function assessments during the first trimester (6-13+6 weeks) were undertaken to ensure measurement precision. Third, our analytical approach incorporates comprehensive covariate adjustment and clinically stratified analyses, strengthening causal inference while maintaining clinical relevance. We believe that these methodological features ensure a rigorous foundation for evaluating the effects of thyroid function on newborn size. However, as any study, ours had some limitations. Thyroid function was assessed only at a single early-pregnancy timepoint (6-13⁺⁶ weeks); while this precludes evaluation of dynamic changes throughout gestation, longitiduonal assessment was not feasible in such a large cohort. Furthermore, urinary iodine concentration (UIC) was not systematically measured. To address the latter, we restricted the population to regions with universal salt iodization to minimize confounding. Nevertheless, the multicenter design and stratified analyses support the generalizability of our findings. Future studies incorporating repeated thyroid measurements and individual UIC data would better delineate temporal relationships and independent effects on perinatal outcomes.

Our study revealed a 3.18% incidence of LBW, aligning with previous Chinese reports (2.77-6.10%) [26, 27]. Current evidence indicates that thyroid dysfunction affects fetal growth. Studies demonstrate that elevated FT4 correlates with reduced birth weight [28, 29], consistent with findings in thyrotoxicosis showing a higher LBW incidence (23.7% vs. 17.7%) [30]. Recent first-trimester data also reveal a similar inverse relationship between FT3 and birth weight [31]. Although findings regarding TSH remain inconsistent, the persistent association between thyroid hormones and birth weight across trimesters [32] collectively suggests a continuous inhibitory effect on fetal growth throughout pregnancy.

In addition, the 21% elevated SGA risk in the highest TSH quintile supports previously reported links between SCH and fetal growth restriction [33, 34]. The 2017 ATA guidelines recommend TPOAb testing to assess thyroid autoimmunity due to its high prevalence [22]. While TPOAb positivity is a recognized predictor of gestational thyroid dysfunction [35-37], our study found no independent association between TPOAb status and reduced birth weight.

Restricted cubic spline analyses revealed nonlinear relationships between TSH/FT4 levels and LBW/SGA risk (P < 0.05). Although quintile analyses suggested monotonic trends, spline models demonstrated accelerated risk elevation at upper-normal hormone levels, indicating threshold effects that categorical analyses may overlook. While the continuous effects of thyroid hormones on birth weight are clinically insignificant (1.43 g per FT4 unit; 5.62 g per TSH unit), our key finding relates to categorical outcomes. When TSH exceeds 2.33 mIU/L, risks of both LBW (aOR = 1.16) and SGA (aOR = 1.20) increase significantly. This threshold-based association supports the 2.5 mIU/L upper limit recommended by major guidelines [38, 39] and justifies targeted monitoring for at-risk individuals. Indeed, early thyroid screening remains clinically meaningful despite minimal per-unit weight effects.

It should be noted that some studies have reported no significant link between thyroid dysfunction and LBW [5, 16, 40], while others identified TPOAb positive in the first trimester as an independent predictor (OR = 7.76, 95% CI: 1.23-48.86, P = 0.029) [8, 36, 37] —a conclusion contrasting with our results, which showed no such association. Moreover, a newly published prospective cohort analysis demonstrated the absence of any significant connection between SCH (whether presenting in the first or third gestational trimester) and the likelihood of delivering SGA neonates., regardless of TPOAb status [41]. We believe these inconsistencies may reflect methodological differences in gestational timing, statistical power, and confounding adjustment across studies.

The efficacy of levothyroxine (L-T4) therapy for SCH in pregnancy remains controversial. While meta-analyses demonstrate significant benefits—one showing a 65% reduction in LBW risk (RR = 0.35, 95% CI: 0.18-0.69) [42] and another reporting a 92% risk reduction (OR = 0.08, 95% CI: 0.01-0.51) [43]—contradictory evidence exists. Retrospective studies by Luo et al. [44]and Han et al. [45] found either no improvement in neonatal outcomes or persistent LBW risk despite treatment (aOR = 2.11, 95% CI: 1.42-3.13). These discrepancies underscore the critical need for better patient stratification. Consequently, future randomized trials should validate whether personalized L-T4 therapy based on screening can effectively reduce LBW and SGA incidence.

Several mechanisms may explain our findings. First, elevated maternal FT4 levels in early pregnancy could increase placental vascular resistance, altering hemodynamics and impairing placental functions such as nutrient supply and waste elimination, ultimately contributing to LBW [1, 28, 46]. This effect may be mediated via placental TSH receptors or modulated by placental deiodinase activity [1, 47]. Second, high FT4 levels may accelerate maternal catabolism, leading to chronic energy deficiency and reduced birth weight [48]. Third, maternal thyroid dysfunction (including SCH) might impair fetal vascular development, while deficiencies in essential metals could disrupt thyroid hormone homeostasis, both potentially increasing susceptibility to LBW and SGA [49, 50]. Coming research efforts should pursue two key objectives: clarifying the causal pathways and testing targeted prevention approaches.

Conclusion

Our findings reinforce that maternal thyroid function, even within subclinical ranges, are significantly associated with fetal growth outcomes. Collectively, our results highlight the potential clinical utility of thyroid monitoring during gestation, especially among women exhibiting FT4 concentrations in the high-normal range or elevated TSH levels.

Abbreviations

LBW: low birth weight; SGA: small for gestational age; BMI: body mass index; CBCS: China Birth Cohort Study; FT4: free thyroxine; TPOAb: thyroid peroxidase antibody; TSH: thyroid-stimulating hormone; ART: Assisted Reproductive Technology.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary figures.

Acknowledgements

We are profoundly grateful to all research participants for their indispensable involvement and dedication. We sincerely appreciate the invaluable contributions of the physicians and healthcare professionals from the following institutions in disease diagnosis and questionnaire collection: Beijing Obstetrics and Gynecology Hospital, Capital Medical University; Maternal and Child Health Care Hospitals of Tongzhou District (Beijing), Henan Province, Hunan Province, and Guiyang; Chengdu Women's and Children's Central Hospital; Shandong Provincial Hospital; Changsha Maternal and Child Health Hospital and Northwest Women's and Children's Hospital. Their expertise was instrumental to this study. We also extend our thanks to the laboratory technicians for their essential contributions to this research.

Funding

Financial support for this study was provided through the following grants: China's National Key R&D Program (Grant No. 2016YFC1000101); Beijing Municipal Science & Technology Commission (Grant No. Z181100001718076); Capital Health Development Research Fund (Grant No. CFH 2022-1-2111).

Author contributions

C.-H. Y., ATP., R.-X. L. and J. L. were responsible for the study conception and design. M.-H. H., R.Z., S.-H. X., S.-F. S., E.-J. Z., S.-Y. L., Z. L., J.-H. L. and H. X. collected data. J. L. carried out the statistical analysis. J. L. prepared the initial manuscript draft. C.-H. Y., ATP., R.-X. L. and J. L. contributed significant revisions for the content of the manuscript. Each coauthor played an integral role in result analysis and interpretation, contributed to multiple rounds of manuscript revisions, and approved the definitive version for submission.

Ethics approval

The research protocol obtained official ethical clearance from the Ethics Committee at Beijing Obstetrics and Gynecology Hospital, Capital Medical University (reference number: 2018-KY-003-02).

Informed consent

In accordance with ethical guidelines, Prior to study initiation, all participants provided written informed consent following full disclosure of study protocols.

Data accessibility

The datasets produced and analyzed in this research can be obtained from the corresponding author upon justified request. Full public deposition is restricted to protect participant confidentiality in accordance with ethical requirements.

Competing Interests

The authors have declared that no competing interest exists.

References

1. Barjaktarovic M, Korevaar TI, Chaker L, Jaddoe VW, de Rijke YB, Visser TJ. et al. The association of maternal thyroid function with placental hemodynamics. Hum Reprod. 2017;32:653-61

2. Dong AC, Stagnaro-Green A. Differences in Diagnostic Criteria Mask the True Prevalence of Thyroid Disease in Pregnancy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Thyroid. 2019;29:278-89

3. Huang K, Su S, Wang X, Hu M, Zhao R, Gao S. et al. Association Between Maternal Thyroid Function in Early Pregnancy and Gestational Diabetes: A Prospective Cohort Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2024;109:e780-e7

4. Hu M, Gao S, Huang K, Wang X, Li J, Li S. et al. Elevated Serum TSH Levels and TPOAb Positivity in Early Pregnancy are Associated with Increased Risk of Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy: A Prospective Cohort Study. Int J Med Sci. 2025;22:575-84

5. Lee SY, Cabral HJ, Aschengrau A, Pearce EN. Associations Between Maternal Thyroid Function in Pregnancy and Obstetric and Perinatal Outcomes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;105:e2015-23

6. Chen GD, Pang TT, Lu XF, Li PS, Zhou ZX, Ye SX. et al. Associations Between Maternal Thyroid Function and Birth Outcomes in Chinese Mother-Child Dyads: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2020;11:611071

7. Mahadik K, Choudhary P, Roy PK. Study of thyroid function in pregnancy, its feto-maternal outcome; a prospective observational study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20:769

8. Xu Y, Li C, Wang W, Yu X, Liu A, Shi Y. et al. Gestational and Postpartum Complications in Patients with First Trimester Thyrotoxicosis: A Prospective Multicenter Cohort Study from Northeast China. Thyroid. 2023;33:762-70

9. Sankoda A, Arata N, Sato S, Umehara N, Morisaki N, Ito Y. et al. Association of Isolated Hypothyroxinemia and Subclinical Hypothyroidism With Birthweight: A Cohort Study in Japan. J Endocr Soc. 2023;7:bvad045

10. Sanin KI, Islam MM, Mahfuz M, Ahmed AMS, Mondal D, Haque R. et al. Micronutrient adequacy is poor, but not associated with stunting between 12-24 months of age: A cohort study findings from a slum area of Bangladesh. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0195072

11. Derakhshan A, Peeters RP, Taylor PN, Bliddal S, Carty DM, Meems M. et al. Association of maternal thyroid function with birthweight: a systematic review and individual-participant data meta-analysis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8:501-10

12. Varley BJ, Nasir RF, Skilton MR, Craig ME, Gow ML. Early Life Determinants of Vascular Structure in Fetuses, Infants, Children, and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Pediatr. 2023;252:101-10.e9

13. Lee AC, Kozuki N, Cousens S, Stevens GA, Blencowe H, Silveira MF. et al. Estimates of burden and consequences of infants born small for gestational age in low and middle income countries with INTERGROWTH-21<sup>st</sup> standard: analysis of CHERG datasets. BMJ. 2017;358:j3677

14. Zhang C, Yang X, Zhang Y, Guo F, Yang S, Peeters RP. et al. Association Between Maternal Thyroid Hormones and Birth Weight at Early and Late Pregnancy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104:5853-63

15. Kumru P, Erdogdu E, Arisoy R, Demirci O, Ozkoral A, Ardic C. et al. Effect of thyroid dysfunction and autoimmunity on pregnancy outcomes in low risk population. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2015;291:1047-54

16. Zhu P, Chu R, Pan S, Lai X, Ran J, Li X. Impact of TPOAb-negative maternal subclinical hypothyroidism in early pregnancy on adverse pregnancy outcomes. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. 2021;12:20420188211054690

17. Magri F, Bellingeri C, De Maggio I, Croce L, Coperchini F, Rotondi M. et al. A first-trimester serum TSH in the 4-10 mIU/L range is associated with obstetric complications in thyroid peroxidase antibody-negative women. J Endocrinol Invest. 2023;46:1407-14

18. Purdue-Smithe AC, Männistö T, Bell GA, Mumford SL, Liu A, Kannan K. et al. The Joint Role of Thyroid Function and Iodine Status on Risk of Preterm Birth and Small for Gestational Age: A Population-Based Nested Case-Control Study of Finnish Women. Nutrients. 2019;11:2573

19. Ozarda Y, Sikaris K, Streichert T, Macri J. Distinguishing reference intervals and clinical decision limits - A review by the IFCC Committee on Reference Intervals and Decision Limits. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2018;55:420-31

20. Yue W, Zhang E, Liu R, Zhang Y, Wang C, Gao S. et al. The China birth cohort study (CBCS). Eur J Epidemiol. 2022;37:295-304

21. Lundgaard MH, Bruun NH, Andersen S, Andersen SL. Birth weight and placental weight in children born to mothers with hypothyroidism. Eur Thyroid J. 2025;14:e250111

22. Alexander EK, Pearce EN, Brent GA, Brown RS, Chen H, Dosiou C. et al. 2017 Guidelines of the American Thyroid Association for the Diagnosis and Management of Thyroid Disease During Pregnancy and the Postpartum. Thyroid. 2017;27:315-89

23. Männistö T, Surcel HM, Bloigu A, Ruokonen A, Hartikainen AL, Järvelin MR. et al. The effect of freezing, thawing, and short- and long-term storage on serum thyrotropin, thyroid hormones, and thyroid autoantibodies: implications for analyzing samples stored in serum banks. Clin Chem. 2007;53:1986-7

24. Krasevec J, Blencowe H, Coffey C, Okwaraji YB, Estevez D, Stevens GA. et al. Study protocol for UNICEF and WHO estimates of global, regional, and national low birthweight prevalence for 2000 to 2020. Gates Open Res. 2022;6:80

25. Villar J, Cheikh Ismail L, Victora CG, Ohuma EO, Bertino E, Altman DG. et al. International standards for newborn weight, length, and head circumference by gestational age and sex: the Newborn Cross-Sectional Study of the INTERGROWTH-21st Project. Lancet. 2014;384:857-68

26. Chen Y, Li G, Ruan Y, Zou L, Wang X, Zhang W. An epidemiological survey on low birth weight infants in China and analysis of outcomes of full-term low birth weight infants. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13:242

27. Tang W, Mu Y, Li X, Wang Y, Liu Z, Li Q. et al. Low birthweight in China: evidence from 441 health facilities between 2012 and 2014. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2017;30:1997-2002

28. Johns LE, Ferguson KK, Cantonwine DE, Mukherjee B, Meeker JD, McElrath TF. Subclinical Changes in Maternal Thyroid Function Parameters in Pregnancy and Fetal Growth. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103:1349-58

29. Bassols J, Prats-Puig A, Soriano-Rodríguez P, García-González MM, Reid J, Martínez-Pascual M. et al. Lower free thyroxin associates with a less favorable metabolic phenotype in healthy pregnant women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:3717-23

30. Harn AMP, Dejkhamron P, Tongsong T, Luewan S. Pregnancy Outcomes among Women with Graves' Hyperthyroidism: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J Clin Med. 2021;10:4495

31. La Verde M, De Franciscis P, Molitierno R, Caniglia FM, Fordellone M, Braca E. et al. Thyroid Hormones in Early Pregnancy and Birth Weight: A Retrospective Study. Biomedicines. 2025;13:542

32. Cai C, Chen W, Vinturache A, Hu P, Lu M, Gu H. et al. Thyroid hormone concentrations in second trimester of gestation and birth outcomes in Shanghai, China. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2021;34:1897-905

33. León G, Murcia M, Rebagliato M, Álvarez-Pedrerol M, Castilla AM, Basterrechea M. et al. Maternal thyroid dysfunction during gestation, preterm delivery, and birthweight. The Infancia y Medio Ambiente Cohort, Spain. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2015;29:113-22

34. Su PY, Huang K, Hao JH, Xu YQ, Yan SQ, Li T. et al. Maternal thyroid function in the first twenty weeks of pregnancy and subsequent fetal and infant development: a prospective population-based cohort study in China. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:3234-41

35. Singh M, Wambua S, Lee SI, Okoth K, Wang Z, Fayaz FFA. et al. Autoimmune diseases and adverse pregnancy outcomes: an umbrella review. BMC Med. 2024;22:94

36. Chen L, Lin D, Lin Z, Ye E, Sun M, Lu X. Maternal thyroid peroxidase antibody positivity and its association with incidence of low birth weight in infants. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1285504

37. Sitoris G, Veltri F, Kleynen P, Cogan A, Belhomme J, Rozenberg S. et al. The Impact of Thyroid Disorders on Clinical Pregnancy Outcomes in a Real-World Study Setting. Thyroid. 2020;30:106-15

38. Stagnaro-Green A, Abalovich M, Alexander E, Azizi F, Mestman J, Negro R. et al. Guidelines of the American Thyroid Association for the diagnosis and management of thyroid disease during pregnancy and postpartum. Thyroid. 2011;21:1081-125

39. Abalovich M, Amino N, Barbour LA, Cobin RH, De Groot LJ, Glinoer D. et al. Management of thyroid dysfunction during pregnancy and postpartum: an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:S1-47

40. Wang S, Teng WP, Li JX, Wang WW, Shan ZY. Effects of maternal subclinical hypothyroidism on obstetrical outcomes during early pregnancy. J Endocrinol Invest. 2012;35:322-5

41. Liu X, Zhang C, Lin Z, Zhu K, He R, Jiang Z. et al. Association of maternal mild hypothyroidism in the first and third trimesters with obstetric and perinatal outcomes: a prospective cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2025;232:480.e1-e19

42. Li J, Shen J, Qin L. Effects of Levothyroxine on Pregnancy Outcomes in Women with Thyroid Dysfunction: A Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Altern Ther Health Med. 2017;23:49-58

43. Geng X, Chen Y, Wang W, Ma J, Wu W, Li N. et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the efficacy and pregnancy outcomes of levothyroxine sodium tablet administration in pregnant women complicated with hypothyroidism. Ann Palliat Med. 2022;11:1441-52

44. Luo J, Yuan J. Effects of Levothyroxine Therapy on Pregnancy and Neonatal Outcomes in Subclinical Hypothyroidism. Int J Gen Med. 2022;15:6811-20

45. Han L, Ma Y, Liang Z, Chen D. Laboratory characteristics analysis of the efficacy of levothyroxine on subclinical hypothyroidism during pregnancy: a single-center retrospective study. Bioengineered. 2021;12:4183-90

46. Adu-Gyamfi EA, Wang YX, Ding YB. The interplay between thyroid hormones and the placenta: a comprehensive review†. Biol Reprod. 2020;102:8-17

47. Luongo C, Trivisano L, Alfano F, Salvatore D. Type 3 deiodinase and consumptive hypothyroidism: a common mechanism for a rare disease. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2013;4:115

48. Sun X, Liu W, Zhang B, Shen X, Hu C, Chen X. et al. Maternal Heavy Metal Exposure, Thyroid Hormones, and Birth Outcomes: A Prospective Cohort Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104:5043-52

49. Blazer S, Moreh-Waterman Y, Miller-Lotan R, Tamir A, Hochberg Z. Maternal hypothyroidism may affect fetal growth and neonatal thyroid function. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:232-41

50. Wu W, Lu J, Ruan X, Ma C, Lu W, Luo Y. et al. Maternal essential metals, thyroid hormones, and fetal growth: Association and mediation analyses in Chinese pregnant women. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2021;68:126809

Author contact

![]() Corresponding authors: Ruixia Liu, Email: liuruixiaedu.cn, ORCID: 0000-0001-5835-4424, Tel.: +86-10-52277607. Address: No. 251 Yaojiayuan Road, Chaoyang District, Beijing 100026, China. Aris T. Papageorghiou, Email: aris.papageorghiouox.ac.uk, Tel.: +44(0)20 8725 0071. Address: John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, OX3 9DU, UK. Chenghong Yin, Email: yinchhedu.cn, ORCID: 0000-0002-2503-3285, Tel.: +86-10-85968401. Address: No. 251 Yaojiayuan Road, Chaoyang District, Beijing 100026, China.

Corresponding authors: Ruixia Liu, Email: liuruixiaedu.cn, ORCID: 0000-0001-5835-4424, Tel.: +86-10-52277607. Address: No. 251 Yaojiayuan Road, Chaoyang District, Beijing 100026, China. Aris T. Papageorghiou, Email: aris.papageorghiouox.ac.uk, Tel.: +44(0)20 8725 0071. Address: John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, OX3 9DU, UK. Chenghong Yin, Email: yinchhedu.cn, ORCID: 0000-0002-2503-3285, Tel.: +86-10-85968401. Address: No. 251 Yaojiayuan Road, Chaoyang District, Beijing 100026, China.

Global reach, higher impact

Global reach, higher impact