Impact Factor

ISSN: 1449-1907

Int J Med Sci 2026; 23(1):301-312. doi:10.7150/ijms.122642 This issue Cite

Research Paper

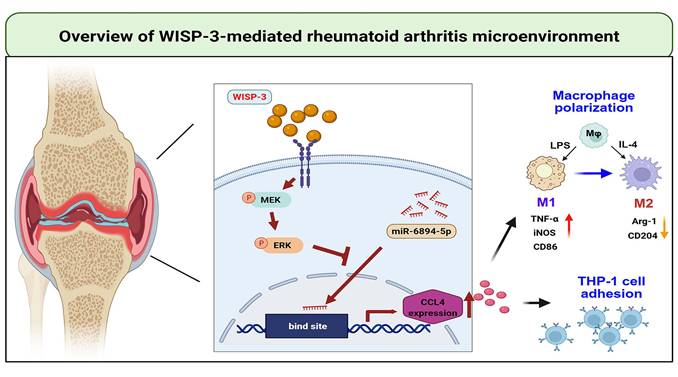

WISP-3 facilitates CCL4-dependent monocyte migration and M1 polarization in rheumatoid arthritis by inhibiting miR-6894-5p

1. Department of Medicine, MacKay Medical University, New Taipei City, Taiwan.

2. Department of Orthopedic Surgery, MacKay Memorial Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan.

3. Department of Post-Baccalaureate Medicine, National Chung-Hsing University, Taichung, Taiwan.

4. Department of Orthopedics, Taichung Veterans General Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan.

5. Translational Medicine Research Center, China Medical University Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan.

6. Department of Research, Taiwan Blood Services Foundation, Taipei, Taiwan.

7. The Director's Office, Shin Kong Wu Ho-Su Memorial Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan.

8. Department of Sports Medicine, College of Health Care, China Medical University, Taichung, Taiwan.

9. Department of Orthopedic Surgery, China Medical University Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan.

10. Department of Orthopedic Surgery, China Medical University Beigang Hospital, Yunlin, Taiwan.

11. Department of Pharmacology, School of Medicine, China Medical University, Taichung, Taiwan.

12. Department of Medical Laboratory Science and Biotechnology, Asia University, Taichung, Taiwan.

13. Chinese Medicine Research Center, China Medical University, Taichung, Taiwan.

14. Translational Medicine Center, Shin-Kong Wu Ho-Su Memorial Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan.

#These authors contributed equally to this work.

Received 2025-7-29; Accepted 2025-10-17; Published 2026-1-1

Abstract

Chronic systemic inflammation and autoimmunity are hallmarks of rheumatoid arthritis (RA), an inflammatory illness that progressively deteriorates joints, resulting in permanent disability. Monocyte adhesion and infiltration into synovial tissue are critical steps in RA progression. WISP-3 (referred to as CCN6) is a member of the CCN family and plays a role in regulating various developmental processes. However, the role of WISP-3 in monocyte adhesion and macrophage polarization in RA remains unknown. Our high-throughput cytokine array data indicate that WISP-3 induces CCL4 synthesis in RA synovial fibroblasts (RASFs), subsequently enhancing monocyte adhesion to the synovium. Result from the GEO database confirm that levels of WISP-3 and CCL4 are markedly higher in RA patients compared to healthy controls. We also elucidated a detailed mechanism by which WISP-3 increases CCL4 synthesis in RASFs and promotes monocyte adhesion to the synovium by reducing miR-6894-5p expression via the MEK and ERK pathways. Furthermore, WISP-3 augments M1 macrophage polarization in the RA microenvironment. Thus, the WISP-3/CCL4 axis may serve as a novel therapeutic goal for RA treatment.

Keywords: rheumatoid arthritis, WISP-3, CCL4, Monocyte adhesion, M1 polarization

Introduction

Chronic systemic inflammation and autoimmunity are hallmarks of rheumatoid arthritis (RA), an inflammatory disease that progressively damages the joints and ultimately leads to permanent disability [1, 2]. Both bone and cartilage are affected by the abnormal proliferation of synovial cells, driven by complex interactions among various cytokines and cell types involved in the pathogenesis of RA [3, 4]. The imbalance between pro- and anti-inflammatory mediators contributes to persistent inflammation, autoimmune dysfunction, and joint destruction [5, 6]. Through the production of chondrolytic enzymes and pro-inflammatory cytokines, rheumatoid arthritis synovial fibroblasts (RASFs) play a central role in initiating and sustaining joint degeneration [7, 8]. Therefore, the pathological state of the synovium should be a critical focus in the development of therapeutic strategies for RA.

Mononuclear cells play an essential role in the progression of RA. Monocytes and macrophages, key phagocytic cells of the innate immune system, are widely distributed throughout various tissues, including joints [9, 10]. They are involved in maintaining tissue homeostasis and protecting against infections [11]. Moreover, these cells interact closely with the adaptive immune system, particularly through their secretory mediators in response to T cell activation [12]. The pathogenesis of RA is critically dependent on the recruitment of monocytes into the joints and their subsequent adhesion to the synovial membrane [12]. Upon migrating to synovial tissues, monocytes differentiate into macrophages and can be polarized into either the M1 or M2 phenotype in response to different environmental stimuli [13]. In RA, pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and TNF-α induce M1 polarization, leading to elevated levels of inflammatory mediators, enhanced cartilage degradation, and increased osteoclast formation [13-15]. M1 macrophages release various pro-inflammatory cytokines that drive the chronic inflammatory response, tissue destruction, and pain characteristic of RA [16]. In contrast, M2 macrophages exert anti-inflammatory and tissue-repairing functions. Patients with RA exhibit accelerated monocyte turnover, shortened circulation time, and a pronounced tendency for monocyte accumulation in the joints [17]. After migrating into the synovium, these monocytes may polarize into M1 macrophages that promote inflammation or into M2 macrophages that contribute to inflammation resolution. Notably, the M1/M2 ratio in the synovial tissue of RA patients is significantly higher than that observed in healthy individuals [18]. Consequently, therapeutic strategies aimed at inhibiting M1 polarization or restoring the M1/M2 balance may hold potential in mitigating joint inflammation and tissue damage in RA.

In addition to cellular dysregulation, the pathogenesis of RA is profoundly influenced by disturbances in gene regulatory mechanisms, particularly those mediated by microRNAs (miRNAs) [19]. miRNAs are small, non-coding RNA molecules of approximately 22 nucleotides that play essential roles in post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression and are evolutionarily conserved components of the cellular regulatory network. They exhibit dynamic and tightly controlled expression patterns, enabling cells to respond precisely to environmental stimuli [20]. Several signaling pathways, including the p53, JAK-STAT, AP-1, MAPK, Toll-like receptor (TLR), and NF-κB pathways, regulate miRNA synthesis and are themselves modulated by miRNA feedback mechanisms, thereby sustaining the chronic inflammatory milieu characteristic of RA [21, 22]. Alterations in these pathways affect immune cell activation and cytokine production, thereby amplifying synovial inflammation. Notably, miRNA expression varies substantially across different macrophage polarization states, allowing macrophages to adapt to inflammatory or anti-inflammatory cues. Dysregulation of specific miRNAs, such as miR-155 and miR-146a, has been shown to disrupt monocyte and macrophage function, contributing to the persistence of inflammation and joint destruction in RA [19, 23]. Therefore, elucidating the specific miRNAs and their upstream regulatory factors involved in macrophage activation may provide new insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying RA and identify potential therapeutic targets.

Six matricellular proteins make up the CCN family, and they play crucial roles in the primary pathophysiological functions of inflammation, migration and angiogenesis [24]. WISP-3 (referred to as CCN6) is part of the CCN family and plays a role in regulating various developmental effects [25]. In RA synovium, WISP-3 mRNA expression is markedly elevated compared with osteoarthritis and normal synovial tissue, and its transcription can be further enhanced by pro-inflammatory cytokines in RASFs [26]. In cartilage, WISP-3 contributes to extracellular matrix homeostasis and exerts complex, dose- and context-specific regulation of matrix metalloproteinases such as ADAMTS-5 and MMP-10 [27]. These findings underscore the context-specific nature of WISP-3: in chondrocytes and cartilage, it helps maintain matrix integrity, whereas in RA FLS, as demonstrated in the present study, it promotes chemokine expression and monocyte adhesion within an inflammatory microenvironment. It is noteworthy that the levels of WISP-3 protein in RA and normal synovium are comparable, indicating that there may not be a coordinated regulation between WISP-3 protein and mRNA [26]. Notably, WISP-3 seems to play a significant part in the progression of juvenile idiopathic arthritis, which encompasses chronic inflammatory arthropathies occurring in childhood [28]. However, the role of WISP-3 in monocyte adhesion to the synovium and polarization during RA remains unknown. Our high-throughput cytokine array data indicate that WISP-3 induces CCL4 production in RASFs, subsequently enhancing monocyte adhesion. Inhibition of miR-6894-5p expression through the MEK and ERK pathways is participated in WISP-3-regulated effects. Interestingly, conditioned medium (CM) from WISP-3-stimulated RASFs augments M1 polarization. Thus, the WISP-3/CCL4 axis represents a novel therapeutic goal for RA treatment.

Material and Methods

Materials

Antibodies against MEK-1 (H-8) (Catalog No: SC-6250) and ERK (D-2) (Catalog No: SC-1647) were sourced from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (CA, USA). Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA) supplied the p-MEK1/2 (Ser221) (166F8) (Catalog No: 2338) and p-p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2) (Thr202/Tyr204) (Catalog No: 4370) antibodies. CCL4 (GTX17201) antibodie was purchased from GeneTex (Hsinchu, Taiwan). β-actin antibody (Catalog No: a5441) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Recombinant human WISP-3 was obtained from PerpoTech, located in Rocky Hill, NJ, USA. All other chemicals used in this study were sourced from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Cell culture

Human RASFs cell line (MH7A) was acquired from RIKEN (Ibaraki, Japan). Human monocyte cell line THP-1 was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). Cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium containing 10% FBS, penicillin, and streptomycin at 37°C under a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 [29]. All experiments were performed with mycoplasma-free cells.

Investigation of the adhesion of monocytes to RASFs

MH7A cells (1 × 105) were seeded in 12-well plates and cultured until they reached approximately 90% confluence. Cells were then stimulated with recombinant WISP-3 (100 ng/mL) for 24 h. In parallel, human monocytes were labeled with BCECF-AM (10 μM; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) for 1 hour at 37°C according to the manufacturer's instructions. After labeling, monocytes were washed, resuspended in fresh medium, and monocytes (1 × 105 cells per well) were subsequently co-cultured with WISP-3-treated MH7A cells for 1 h at 37 °C. Non-adherent monocytes were removed by gentle washing with PBS, while adherent monocytes were visualized and quantified using a fluorescence microscope. Five randomly selected fields per well were analyzed using ImageJ for fluorescence intensity and cell counts [30].

Human chemokine antibody array

Secreted chemokines were analyzed using the Human Chemokine Antibody Array C1 (RayBiotech, Inc., Norcross, GA, USA; Cat. No. AAH-CHE-1). MH7A cells were cultured under standard conditions until ~70-80% confluence. To reduce background signals, cells were serum-starved in medium containing 0% FBS for 12-16 h before stimulation. Cells were then treated with recombinant WISP-3 (100 ng/mL) for 24 h, and the protein was collected. The experiment was performed according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, array membranes pre-coated with capture antibodies were blocked with the supplied blocking buffer, then incubated with 1 mL of each sample (cell lysis). After washing, membranes were incubated with the Biotinylated Antibody Cocktail, followed by HRP-conjugated streptavidin. The Fujifilm LAS-3000 imaging equipment was used to view the blot membranes.

Prediction of miRNAs targeting CCL4

To predict miRNAs that may target CCL4, we used the miRWalk database (http://mirwalk.umm.uni-heidelberg.de/). Candidate predictions were cross-validated with the miRDB database, applying a confidence threshold of ≥0.8. Through this combined approach, we identified five candidate miRNAs with potential binding affinity for CCL4. The primer sequences used for subsequent validation are provided in Table 1.

List of PCR primer used for the experiments

| Target mRNA | Forward primer (5'→3') | Reverse primer (5'→3') |

|---|---|---|

| CCL4 | CTGTGCTGATCCCAGTGAATC | TCAGTTCAGTTCCAGGTCATACA |

| CCL5 | CCAGCAGTCGTCTTTGTCAC | CTCTGGGTTGGCACACACTT |

| GAPDH | ACCACAGTCCATGCCATCAC | TCCACCACCCTGTTGCTGTA |

| Target miRNA | Forward primer (5'→3') | |

| has-miR-922 | GCAGCAGAGAATAGGACTACGTC | |

| has-miR-3619-3p | GGGACCATCCTGCCTGCTGTGG | |

| has-miR-3919 | GCAGAGAACAAAGGACTCAGT | |

| has-miR-4516 | GGGAGAAGGGTCGGGGC | |

| has-miR-6894-5p | AGGAGGATGGAGAGCTGGGCCAGA | |

Real-time qPCR

As directed by the manufacturer, RNA was isolated from RASFs using a TRIzol kit (MDBio, Taiwan). Using a NanovueTM Spectrophotometer (GE Healthcare, WI, USA), the quantity and quality of the RNA were evaluated based on A260 readings. cDNA synthesis was performed using an M-MLV RT kit (Invitrogen, CA, USA) and 1 μg of total RNA in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. The KAPA SYBR® FAST qPCR Kit was supplied by Applied Biosystems, CA, USA, to perform real-time qPCR [31, 32]. Primer sequences were designed using a PrimerBank, and the detailed sequences are listed in Table 1.

Western blot analysis

The extracted proteins (30 μg) were resolved using SDS-PAGE, and PVDF membranes were then transferred in accordance with the protocols described in our previous publications [33, 34]. After blocking the membranes for an hour in PBST containing 4% non-fat milk, they were treated with primary antibodies and secondary antibodies conjugated with HRP for an additional hour. A computer densitometer equipped with an ImageQuant LAS4000 (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) was used to measure the amount of protein.

Bioinformatics analysis

Publicly available transcriptome data were obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (accession number GSE77298). This dataset includes synovial biopsy specimens from patients with end-stage rheumatoid arthritis (RA; n = 16) and from individuals without joint disease (healthy controls, HC; n = 7). In particular, the expression levels of WISP-3 (WNT1-inducible signaling pathway protein 3), CCL4, CCL5, CD14, CD68, TNFα, iNOS, CD86, Arg-1, and CD204 were extracted from the dataset for focused evaluation. The differential expression profiles of these genes were visualized using boxplots generated in GraphPad Prism 8.0 software to illustrate their relative enrichment in RA compared with HC [35].

Cell transfection

Small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) targeting CCL4, MEK, ERK, and control siRNA were synthesized by Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, USA). Control mimic, miR-29b-3p mimic, and Lipofectamine 2000 were obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). Transient transfection of siRNA or miRNA mimic was performed using Lipofectamine 2000 in accordance with the manufacturer's protocol. MH7A cells were seeded in a 6-well plate (5 × 10⁵ cells per well) and cultured for 16 h until reaching 80% confluence. One hour before transfection, the culture medium was replaced with serum- and an-tibiotic-free medium. Cells were incubated with transfection mixtures containing 100 nM silencing siRNA, control siRNA, miR-6894-5p, or control mimic for 24 h. Cells were harvested for further analysis by qPCR or Western blot to assess knockdown efficiency and downstream effects [36].

THP-1 differentiation and macrophage polarization

THP-1 monocytes were seeded at a density of 1 × 106 cells per mL per well in 6-well plates. To induce differentiation into M0 macrophages, cells were treated with 200 nM phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) for 24 hours under standard culture conditions (37°C, 5% CO₂). Following this period, cells ceased proliferation and adopted a macrophage-like phenotype (M0). Subsequently, M0 macrophages were further stimulated for an additional 24 hours with CM derived from WISP-3-treated MH7A cultures. After polarization treatment, total RNA was extracted, and the expression of M1 (e.g., TNF-α, iNOS, CD86) and M2 (e.g., Arg-1, CD204) macrophage markers was quantified by qPCR.

Statistical analysis

Quantified data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 8.0 software. All values are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical significance between experiment groups was evaluated using the Student's t-test to compare two unpaired groups. p<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

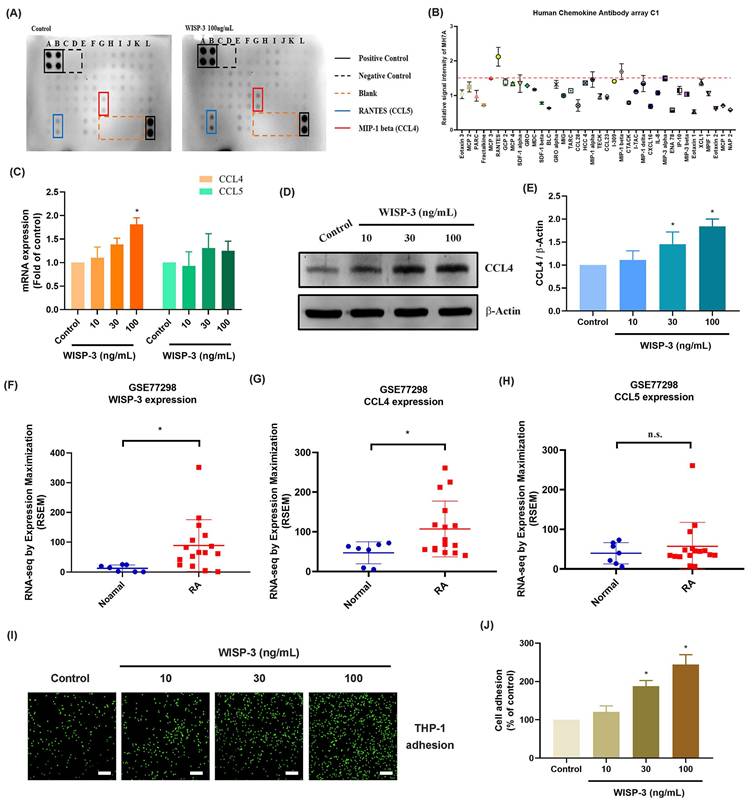

WISP-3 promotes CCL4 production in RASFs and facilitates monocyte adhesion

WISP-3 has a reported function in cartilage growth and maintenance during arthritis [27]. We therefore investigated the functions of WISP-3 in cytokine production in RASFs. High-throughput cytokine array data indicated that WISP-3 most strongly upregulated CCL4 and CCL5 expression (Fig. 1A&B). However, RASFs stimulated with WISP-3 markedly enhanced CCL4, but not CCL5, mRNA expression in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 1C). Additionally, WISP-3 increased CCL4 protein production in RASFs (Fig. 1D&E). Data from the GEO database also confirm that WISP-3 and CCL4, but not CCL5, are elevated in RA patients compared to healthy controls (Fig. 1F-H). Interestingly, stimulation of RASFs with WISP-3 promoted monocyte adhesion to RASFs (Fig. 1I&J), whereas CCL4 siRNA significantly inhibited WISP-3-induced monocyte adhesion (Fig. 1K&L). Thus, WISP-3 induces CCL4 synthesis in RASFs, which in turn promotes monocyte adhesion.

WISP-3 promotes CCL4 production in RASFs and enhances monocyte adhesion. (A&B) Results of cytokine array showing the expression of inflammatory factors by RASFs treated with WISP-3 for 24 h. (C-E) RASFs were treated with WISP-3 for 24 h, the CCL4 expression was examined by qPCR and Western blotting. (F-H) The levels of WISP-3, CCL4 and CCL5 determined using the GSE77298 dataset. (I&J) Fluorescence microscope images of THP-1 cells adhered to RASFs, following incubation with WISP-3 for 24 h. (K&L) Representative fluorescence images and quantitative analysis of THP-1 monocyte adhesion to RASFs treated with WISP-3 (100 ng/mL). Scale bar = 100 µm. All experiments were repeated 3 to 5 times. * p < 0.05 compared with the control group.

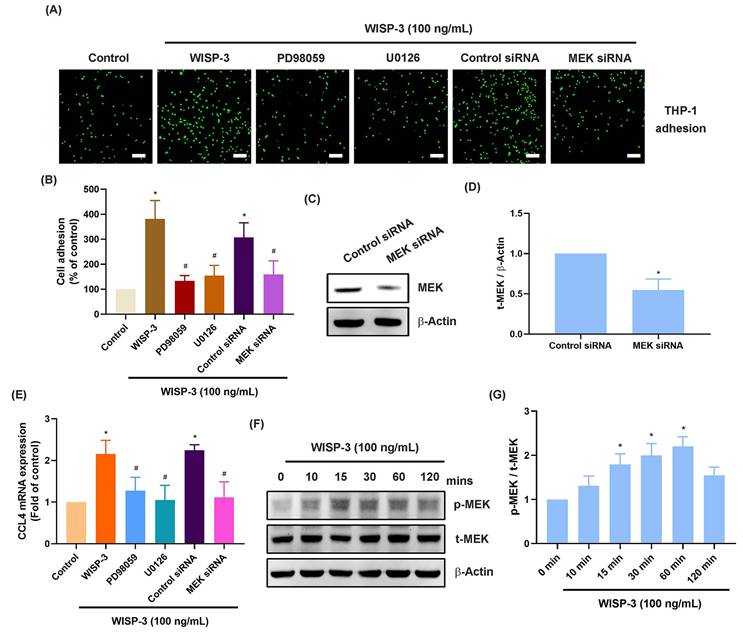

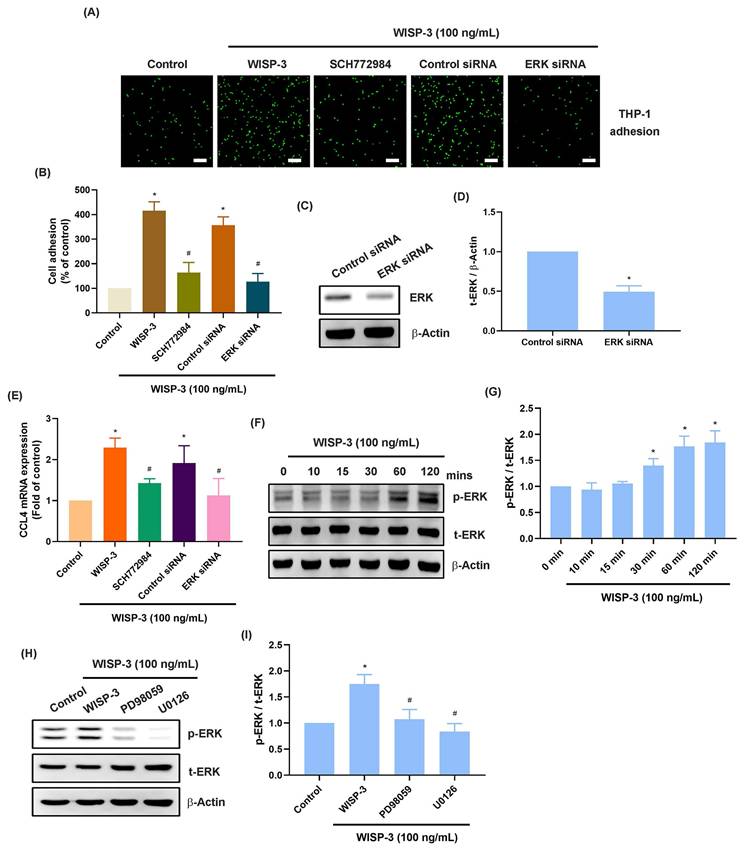

WISP-3 promotes CCL4 production in RASFs and subsequently facilitates monocyte adhesion by reducing miR-6894-5p via the MEK and ERK pathways

The MEK and ERK signaling cascades are crucial for monocyte adhesion and infiltration during arthritis [37, 38]. Treatment of RASFs with MEK inhibitors (PD98059 and U0126) abolished WISP-3-enhanced promotion of monocyte adhesion and CCL4 production (Fig. 2A-E). Transfection of RASFs with MEK siRNA produced similar results (Fig. 2A-E). CCL4 administration increased MEK phosphorylation in RASFs (Fig. 2F&G). Furthermore, the ERK inhibitor (SCH772984) and ERK siRNA blocked WISP-3-enhanced monocyte adhesion and CCL4 expression (Fig. 3A-E). CCL4 stimulation also augmented ERK phosphorylation, which was reversed by application with MEK inhibitors (Fig. 3F-I), indicating that the MEK/ERK signaling pathway controls WISP-3-mediated CCL4 synthesis and monocyte adhesion to RASFs.

MEK is involved in WISP-3-induced CCL4 production and monocyte adhesion. (A-E) THP-1 adhesion and CCL4 expression in RASFs incubated with MEK inhibitors (PD98059 and U0126) or transfected with MEK siRNA and then stimulated with WISP-3 for 24 h. (C&D) RASFs were transfected with MEK siRNA, the MEK expression was examined by Western blotting. (F&G) RASFs were treated with WISP-3, the MEK phosphorylation was examined by Western blotting. Scale bar = 100 µm. All experiments were repeated 3 to 5 times. * p < 0.05 compared with the control group. # p < 0.05 compared with the WISP-3-treated group.

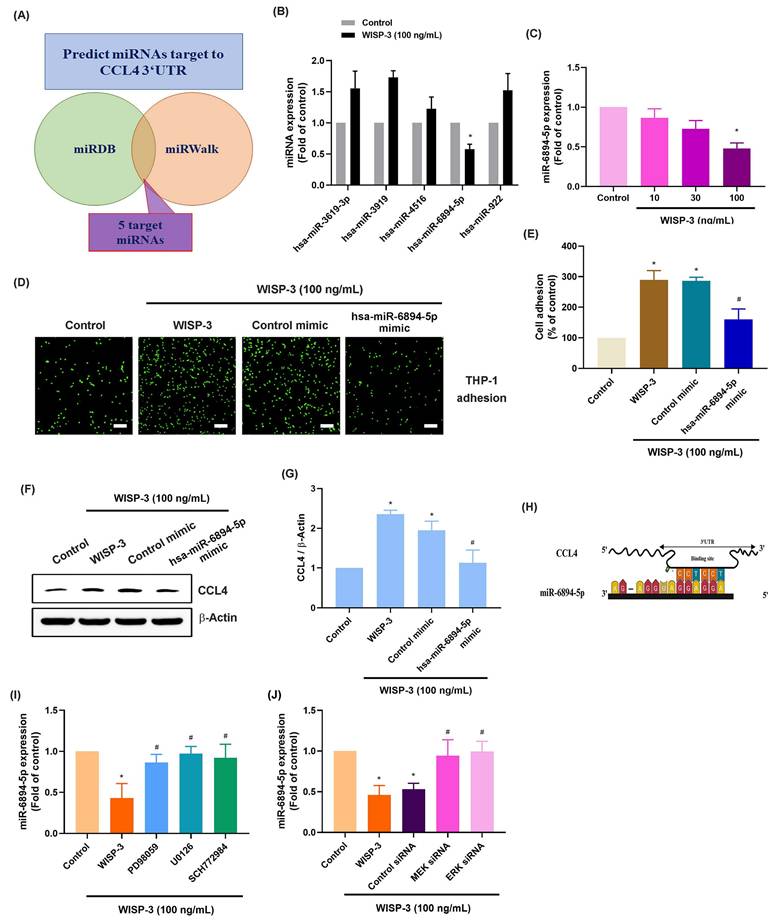

miRNAs are small non-coding RNAs that control different pathological functions in RA [39, 40]. Employing two bioinformatics tools (miRDB and miRWalk), we discovered five miRNAs that directly interact with the 3' UTRs of CCL4 (Fig. 4A). WISP-3 treatment primarily diminished miR-6894-5p expression among them (Fig. 4B). RASFs incubated with WISP-3 showed a reduction in miR-6894-5p expression that was dependent on the concentration (Fig. 4C). Further experiments were conducted to determine whether WISP-3 promotes monocyte adhesion by regulating miR-6894-5p. To test this, RASFs were transfected with a miR-6894-5p mimic, which effectively reversed the WISP-3-induced increases in monocyte adhesion and CCL4 production (Fig. 4D-G). Consistent with these findings, bioinformatic analysis predicted a direct binding site for miR-6894-5p within the 3′ UTR of CCL4 mRNA (Fig. 4H), suggesting that CCL4 is a potential downstream target of miR-6894-5p. Moreover, both pharmacological inhibition (MEK and ERK inhibitors) and siRNA-mediated knockdown of MEK and ERK during incubation reversed the effects induced by WISP-3 on miR-6894-5p production (Fig. 4I-J). This indicates that WISP-3 enhances CCL4 synthesis and monocyte adhesion by reducing miR-6894-5p through the MEK and ERK pathway.

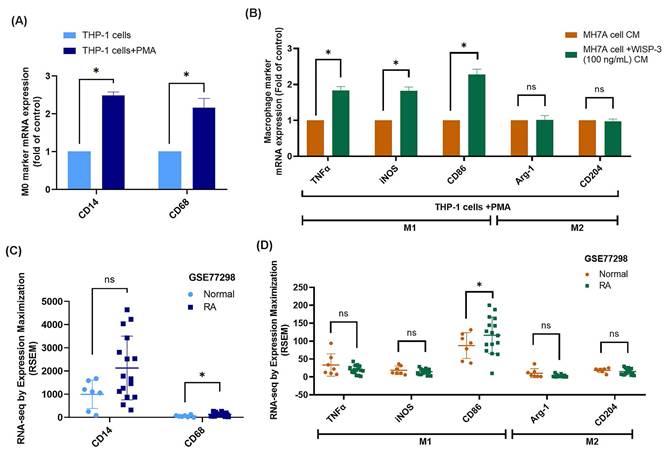

WISP-3-treated RASFs enhance M1 macrophage polarization

Migrated monocytes/macrophages in the synovial membrane polarize into either the M1 or M2 phenotype during RA development [41]. Upon stimulation with PMA, the mRNA expression of M0 markers CD14 and CD68 was significantly increased, confirming the differentiation of THP-1 cells into M0 macrophages (Fig. 5A). When these M0 macrophages were exposed to CM from WISP-3-stimulated RASFs, their polarization shifted toward the M1 phenotype, as evidenced by increased expression of TNF-α, iNOS, and CD86, whereas M2 markers (Arg-1, CD204) remained unchanged (Fig. 5B). Subsequently, analysis of the GSE77298 dataset showed that CD68 expression was significantly elevated in RA synovial tissues compared with normal controls, while CD14 levels were not significantly different (Fig. 5C). Moreover, the M1 marker CD86 was markedly upregulated in RA samples, whereas TNF-α, iNOS, and the M2 markers Arg-1 and CD204 displayed no significant alterations (Fig. 5D). These findings collectively indicate that WISP-3 promotes macrophage polarization toward a pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype, which may contribute to the inflammatory microenvironment of RA.

ERK is involved in WISP-3-induced CCL4 production and monocyte adhesion. (A-E) THP-1 adhesion and CCL4 expression in RASFs incubated with ERK inhibitor (SCH772984) or transfected with ERK siRNA and then stimulated with WISP-3 for 24 h. (C&D) RASFs were transfected with ERK siRNA, the ERK expression was examined by Western blotting. (F&G) RASFs were treated with WISP-3, the MEK phosphorylation was examined by Western blotting. (H&I) RASFs were treated with MEK inhibitors then stimulated with WISP-3, the ERK phosphorylation was examined by Western blotting. Scale bar = 100 µm. All experiments were repeated 3 to 5 times. * p < 0.05 compared with the control group. # p < 0.05 compared with the WISP-3-treated group.

miR-6894-5p controls WISP-3-induced CCL4 production and monocyte adhesion. (A) The diagrams illustrate the selection of miRNA candidates aimed at CCL4. (B&C) RASFs were treated with WISP-3 for 24 h, the indicated miRNA expression was examined by qPCR. (D-G) THP-1 adhesion and CCL4 expression in RASFs transfected with miR-6894-5p mimic and then stimulated with WISP-3 for 24 h. (H) Schematic illustration of the predicted binding site for miR-6894-5p within the 3′-UTR of CCL4 mRNA, showing the complementary base-pairing interaction. (I&J) RASFs were treated with MEK and ERK inhibitors or siRNA then stimulated with WISP-3 for 24 h, the miR-6894-5p expression was examined by qPCR. Scale bar = 100 µm. All experiments were repeated 3 to 5 times. * p < 0.05 compared with the control group. # p < 0.05 compared with the WISP-3-treated group.

WISP-3 enhances M1 macrophage polarization. (A) qPCR analysis of THP-1 cells after a 24 h incubation with PMA. (B) mRNA expression analysis via qPCR following a 24 h treatment of RASFs with WISP-3 and subsequent application of conditioned medium to M0 macrophages. (C&D) Analysis of RNA-seq data from the GEO dataset GSE77298 showing expression levels of macrophage markers in synovial tissues from normal and RA patients. All experiments were repeated 3 to 5 times. * p < 0.05 compared with the control group.

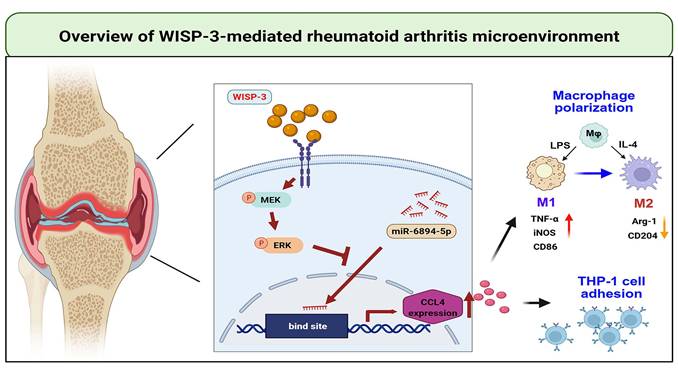

Schematic diagram illustrating the mechanism underlying the monocyte adhesion and M1 polarization of WISP-3 in RA progression. WISP-3 increases CCL4 synthesis in RASFs and promotes monocyte adhesion to the synovium by inhibiting miR-6894-5p expression through the MEK and ERK pathways. Furthermore, WISP-3 augments M1 macrophage polarization in the RA microenvironment.

Discussion

RA's autoimmune inflammatory nature leads to irreversible damage to the affected joints, while the cause of immune system dysfunction remains not fully understood [42]. Common features encompass synovial inflammation and the infiltration of immune cells, with activated synovial fibroblasts playing a role in joint inflammation and cartilage destruction through the production of proinflammatory mediators. This contributes to a "vicious cycle" of disease activity within the RA synovial microenvironment [43]. We used RASFs as an experimental cell model. A high-throughput cytokine array identified CCL4 as the most potent chemokine induced by WISP-3 stimulation in RASFs. We also demonstrated that WISP-3 promotes CCL4 generation in RASFs and augments monocyte adhesion by diminishing miR-6894-5p via the MEK and ERK pathways. Importantly, CM from WISP-3-treated RASFs promotes macrophage polarization into the M1 phenotype. The WISP-3/CCL4 axis may serve as a potential therapeutic strategy for RA remedy.

Macrophages display extraordinary plasticity, capable of polarizing from a neutral state (M0) to a pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype in response to stimuli like LPS and IFN-γ. Polarization takes on added importance due to the fact that a heightened M1/M2 ratio can exacerbate inflammation and tissue injury, thereby aiding in the advancement of the disease [44, 45]. Macrophages' capacity to alternate between these phenotypes highlights their promise as therapeutic targets. M1 macrophage markers are elevated in RA patients compared to healthy individuals [37]. Our results indicate that CM from WISP-3-stimulated RASFs promotes M1 macrophage polarization. These data suggest that pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages contribute to WISP-3-mediated RA development.

The MEK and ERK signaling pathways are essential for numerous biological process, including differentiation, proliferation and apoptosis [46, 47]. Studies on RA have demonstrated that NGF enhances monocyte adhesion through activation of the TrkA, MEK/ERK, and AP-1 signaling cascades [37]. Similarly, nesfatin-1 promotes monocyte migration by upregulating CCL2 expression via the MEK/ERK and p38 signaling pathways [38]. These findings highlight the pivotal role of MEK and ERK signaling in the pathogenesis of RA. Consistent with these observations, our data show that pharmacological inhibition of MEK or ERK effectively blocked WISP-3-induced CCL4 expression and monocyte adhesion. Moreover, siRNA-mediated knockdown of MEK and ERK produced comparable effects, further confirming their involvement in this process. In addition, WISP-3 stimulation markedly enhanced the phosphorylation of MEK and ERK. Interestingly, pretreatment with MEK inhibitors suppressed WISP-3-induced ERK phosphorylation, indicating that ERK acts downstream of MEK and participates in WISP-3-mediated CCL4 synthesis and monocyte adhesion.

miRNAs are crucial post-transcriptional regulators that modulate gene expression through complete or partial base pairing with the 3′UTR of target mRNAs, thereby suppressing translation or promoting mRNA degradation [48, 49]. Growing evidence suggests that dysregulated miRNA-target interactions contribute to the chronic inflammation and joint destruction characteristic of rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and manipulating these pathways may represent a promising therapeutic strategy [48, 49]. For instance, miR-103a-3p mediates TNF-α-induced synovial inflammation and bone erosion by targeting MAP3K7 and DKK1 [50], while miR-548aj-3p and miR-3127-3p attenuate RANKL-driven expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and matrix-degrading enzymes in both osteoarthritis and RA [51]. In oncology, circAFF2 acts as a molecular “sponge” that sequesters miR-6894-5p, relieving its repression of ANTXR1 and thereby facilitating gastric cancer progression [52]. However, the biological function of miR-6894-5p in RA has not been previously reported. In the present study, we identified miR-6894-5p as a novel downstream target involved in WISP-3-mediated signaling in RA synovial fibroblasts. Bioinformatic prediction and experimental validation revealed that miR-6894-5p directly interacts with the 3′UTR of CCL4 mRNA. WISP-3 stimulation significantly suppressed miR-6894-5p expression, leading to increased CCL4 production and enhanced monocyte adhesion. Conversely, transfection of a miR-6894-5p mimic reversed these effects, confirming the inhibitory role of this miRNA in WISP-3-driven pro-inflammatory responses. Moreover, inhibition of miR-6894-5p by WISP-3 was abolished by blocking the MEK and ERK signaling pathways, indicating that WISP-3 regulates CCL4 synthesis and monocyte adhesion through MEK/ERK-dependent suppression of miR-6894-5p. Together, these findings uncover a novel WISP-3/MEK-ERK/miR-6894-5p/CCL4 axis that contributes to monocyte recruitment and inflammation in RA, providing new insight into the post-transcriptional mechanisms underlying RA pathogenesis and potential targets for therapeutic intervention.

In conclusion, we demonstrate that WISP-3 increases CCL4 synthesis in RASFs and promotes monocyte adhesion to the synovium by inhibiting miR-6894-5p expression through the MEK and ERK pathways. Furthermore, WISP-3 augments M1 macrophage polarization in the RA microenvironment (Fig. 6). Targeting the WISP-3/CCL4 axis may serve as a potential therapeutic strategy for RA treatment.

Study Limitations

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the functional experiments were conducted using immortalized cell lines rather than primary synovial fibroblasts and macrophages from RA patients, which may not fully recapitulate the complexity of the in vivo environment. Second, although our in vitro findings (Fig. 5A&B) demonstrated a clear shift of macrophages toward the M1 phenotype upon exposure to WISP-3-stimulated conditioned medium, the transcriptomic analysis of clinical synovial tissues (Fig. 5C&D) showed only partial concordance, with less pronounced differences in M1 marker expression. This discrepancy may reflect heterogeneity among patients, including variations in disease stage, treatment history, or local cytokine milieu, which could influence macrophage polarization in vivo. In early or treated RA, for example, the M1 signature may be less dominant or dynamically regulated. Finally, additional validation using primary RA samples and in vivo arthritis models will be necessary to confirm the relevance of the WISP-3/CCL4 axis and its association with macrophage polarization during disease progression.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Science and Technology Council (NSTC 113-2320-B-039-049-MY3; NSTC 112-2314-B-075A-008; NSTC 114-2314-B-195-025; NSTC 113-2314-B-341-004; and NSTC 114-2314-B-341-007-MY3), China Medical University Hospital (DMR-114-003), China Medical University (CMU114-ASIA-01), Shin Kong Wu Ho-Su Memorial Hospital (2025SKHBND002 and 2025SKHBDR004), MacKay Memorial Hospital (MMH-114-89 and MMH-115-068), and Taichung Veterans General Hospital (TCVGH-1125104B; TCVGH-1141704B).

Author contributions

Chih-Hsin Tang and Chih-Yang Lin contributed to the conceptualization and funding acquisition of the study. Guo-Shou Wang and Kun-Tsan Lee were responsible for data curation, investigation, and validation. Syuan-Ling Lin conducted the formal analysis, developed the methodology together with Guo-Shou Wang, and managed the software implementation. Sheng-Mou Hou provided supervision and, along with Yi-Chin Fong, contributed essential resources. The original draft was written by Chih-Hsin Tang, and Chih-Yang Lin reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors have declared that no competing interest exists.

References

1. Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Barton A, Burmester GR, Emery P, Firestein GS. et al. Rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4:18001

2. Smolen JS, Aletaha D, McInnes IB. Rheumatoid arthritis. The Lancet. 2016;388:2023-38

3. Kondo N, Kuroda T, Kobayashi D. Cytokine Networks in the Pathogenesis of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 22

4. Su CM, Tsai CH, Chen HT, Wu YS, Yang SF, Tang CH. Melatonin Regulates Rheumatoid Synovial Fibroblasts-Related Inflammation: Implications for Pathological Skeletal Muscle Treatment. J Pineal Res. 2024;76:e13009

5. Falconer J, Murphy AN, Young SP, Clark AR, Tiziani S, Guma M. et al. Review: Synovial Cell Metabolism and Chronic Inflammation in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis & Rheumatology. 2018;70:984-99

6. Nygaard G, Firestein GS. Restoring synovial homeostasis in rheumatoid arthritis by targeting fibroblast-like synoviocytes. Nature Reviews Rheumatology. 2020;16:316-33

7. MᵃᶜDonald IJ, Liu SC, Huang CC, Kuo SJ, Tsai CH, Tang CH. Associations between Adipokines in Arthritic Disease and Implications for Obesity. International journal of molecular sciences. 2019 20

8. Wu MH, Tsai CH, Huang YL, Fong YC, Tang CH. Visfatin Promotes IL-6 and TNF-alpha Production in Human Synovial Fibroblasts by Repressing miR-199a-5p through ERK, p38 and JNK Signaling Pathways. International journal of molecular sciences. 2018 19

9. Zhang H, Cai D, Bai X. Macrophages regulate the progression of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2020;28:555-61

10. Zhang H, Lin C, Zeng C, Wang Z, Wang H, Lu J. et al. Synovial macrophage M1 polarisation exacerbates experimental osteoarthritis partially through R-spondin-2. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2018;77:1524-34

11. Wynn TA, Chawla A, Pollard JW. Macrophage biology in development, homeostasis and disease. Nature. 2013;496:445-55

12. Funes SC, Rios M, Escobar-Vera J, Kalergis AM. Implications of macrophage polarization in autoimmunity. Immunology. 2018;154:186-95

13. Estrada McDermott J, Pezzanite L, Goodrich L, Santangelo K, Chow L, Dow S. et al. Role of Innate Immunity in Initiation and Progression of Osteoarthritis, with Emphasis on Horses. Animals (Basel). 2021 11

14. Donell S. Subchondral bone remodelling in osteoarthritis. EFORT Open Rev. 2019;4:221-9

15. Sun Y, Li J, Xie X, Gu F, Sui Z, Zhang K. et al. Macrophage-Osteoclast Associations: Origin, Polarization, and Subgroups. Front Immunol. 2021;12:778078

16. Song Y, Gao N, Yang Z, Zhang L, Wang Y, Zhang S. et al. Characteristics, polarization and targeted therapy of mononuclear macrophages in rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Transl Res. 2023;15:2109-21

17. Cutolo M, Campitiello R, Gotelli E, Soldano S. The Role of M1/M2 Macrophage Polarization in Rheumatoid Arthritis Synovitis. Front Immunol. 2022;13:867260

18. Zhu W, Li X, Fang S, Zhang X, Wang Y, Zhang T. et al. Anti-Citrullinated Protein Antibodies Induce Macrophage Subset Disequilibrium in RA Patients. Inflammation. 2015;38:2067-75

19. Qamar T, Ansari MS, Masihuddin, Mukherjee S. MicroRNAs as Biomarker in Rheumatoid Arthritis: Pathogenesis to Clinical Relevance. J Cell Biochem. 2025;126:e30690

20. Hu R, O'Connell RM. MicroRNA control in the development of systemic autoimmunity. Arthritis research & therapy. 2013;15:202

21. Miller CH, Smith SM, Elguindy M, Zhang T, Xiang JZ, Hu X. et al. RBP-J-Regulated miR-182 Promotes TNF-alpha-Induced Osteoclastogenesis. Journal of immunology. 2016;196:4977-86

22. Chen J, Liu M, Luo X, Peng L, Zhao Z, He C. et al. Exosomal miRNA-486-5p derived from rheumatoid arthritis fibroblast-like synoviocytes induces osteoblast differentiation through the Tob1/BMP/Smad pathway. Biomater Sci. 2020;8:3430-42

23. Chen Q, Wang H, Liu Y, Song Y, Lai L, Han Q. et al. Inducible microRNA-223 down-regulation promotes TLR-triggered IL-6 and IL-1beta production in macrophages by targeting STAT3. PloS one. 2012;7:e42971

24. Jun JI, Lau LF. Taking aim at the extracellular matrix: CCN proteins as emerging therapeutic targets. Nature reviews Drug discovery. 2011;10:945-63

25. MacDonald IJ, Huang CC, Liu SC, Lin YY, Tang CH. Targeting CCN Proteins in Rheumatoid Arthritis and Osteoarthritis. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 22

26. Cheon H, Boyle DL, Firestein GS. Wnt1 inducible signaling pathway protein-3 regulation and microsatellite structure in arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:2106-14

27. Baker N, Sharpe P, Culley K, Otero M, Bevan D, Newham P. et al. Dual regulation of metalloproteinase expression in chondrocytes by Wnt-1-inducible signaling pathway protein 3/CCN6. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2012;64:2289-99

28. Martini A, Lovell DJ. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis: state of the art and future perspectives. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2010;69:1260-3

29. Lin YY, Ko CY, Liu SC, Wang YH, Hsu CJ, Tsai CH. et al. miR-144-3p ameliorates the progression of osteoarthritis by targeting IL-1β: Potential therapeutic implications. J Cell Physiol. 2021;236:6988-7000

30. Liu SC, Law YY, Wu YY, Huang YL, Tsai CH, Chen WC. et al. Fibrosis factor CTGF facilitates VCAM-1-dependent monocyte adhesion to osteoarthritis synovial fibroblasts via the FAK and JNK pathways. Mol Med Rep. 2025 31

31. Liu SC, Tsai CH, Wu TY, Tsai CH, Tsai FJ, Chung JG. et al. Soya-cerebroside reduces IL-1β-induced MMP-1 production in chondrocytes and inhibits cartilage degradation: implications for the treatment of osteoarthritis. Food Agr Immunol. 2019;30:620-32

32. Achudhan D, Liu SC, Lin YY, Lee HP, Wang SW, Huang WC. et al. Antcin K inhibits VEGF-dependent angiogenesis in human rheumatoid arthritis synovial fibroblasts. Journal of food biochemistry. 2022;46:e14022

33. Lee HP, Chen PC, Wang SW, Fong YC, Tsai CH, Tsai FJ. et al. Plumbagin suppresses endothelial progenitor cell-related angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo. Journal of Functional Foods. 2019;52:537-44

34. Lee HP, Wang SW, Wu YC, Lin LW, Tsai FJ, Yang JS. et al. Soya-cerebroside inhibits VEGF-facilitated angiogenesis in endothelial progenitor cells. Food Agr Immunol. 2020;31:193-204

35. Lin LW, Lin TH, Swain S, Fang JK, Guo JH, Yang SF. et al. Melatonin Inhibits ET-1 Production to Break Crosstalk Between Prostate Cancer and Bone Cells: Implication for Osteoblastic Bone Metastasis Treatment. J Pineal Res. 2024;76:e70000

36. Lin SL, Yang SY, Tsai CH, Fong YC, Chen WL, Liu JF. et al. Nerve growth factor promote VCAM-1-dependent monocyte adhesion and M2 polarization in osteosarcoma microenvironment: Implications for larotrectinib therapy. Int J Biol Sci. 2024;20:4114-27

37. Lin CY, Lee KT, Lin YY, Tsai CH, Ko CY, Fong YC. et al. NGF facilitates ICAM-1-dependent monocyte adhesion and M1 macrophage polarization in rheumatoid arthritis. International immunopharmacology. 2024;130:111733

38. Chang JW, Liu SC, Lin YY, He XY, Wu YS, Su CM. et al. Nesfatin-1 Stimulates CCL2-dependent Monocyte Migration And M1 Macrophage Polarization: Implications For Rheumatoid Arthritis Therapy. Int J Biol Sci. 2023;19:281-93

39. Chang TK, Ho TL, Lin YY, Thuong LHH, Lai KY, Tsai CH. et al. Ugonin P facilitates chondrogenic properties in chondrocytes by inhibiting miR-3074-5p production: implications for the treatment of arthritic disorders. International journal of biological sciences. 2025;21:1378-90

40. Chang TK, Zhong YH, Liu SC, Huang CC, Tsai CH, Lee HP. et al. Apelin Promotes Endothelial Progenitor Cell Angiogenesis in Rheumatoid Arthritis Disease via the miR-525-5p/Angiopoietin-1 Pathway. Front Immunol. 2021;12:737990

41. Chang JW, Tang CH. The role of macrophage polarization in rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis: Pathogenesis and therapeutic strategies. Int Immunopharmacol. 2024;142:113056

42. Gravallese EM, Firestein GS. Rheumatoid Arthritis — Common Origins, Divergent Mechanisms. New England Journal of Medicine. 2023;388:529-42

43. Bartok B, Firestein GS. Fibroblast-like synoviocytes: key effector cells in rheumatoid arthritis. Immunological reviews. 2010;233:233-55

44. Locati M, Curtale G, Mantovani A. Diversity, Mechanisms, and Significance of Macrophage Plasticity. Annu Rev Pathol. 2020;15:123-47

45. Shapouri-Moghaddam A, Mohammadian S, Vazini H, Taghadosi M, Esmaeili SA, Mardani F. et al. Macrophage plasticity, polarization, and function in health and disease. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233:6425-40

46. Song CY, Chang SL, Lin CY, Tsai CH, Yang SY, Fong YC. et al. Visfatin-Induced Inhibition of miR-1264 Facilitates PDGF-C Synthesis in Chondrosarcoma Cells and Enhances Endothelial Progenitor Cell Angiogenesis. Cells. 2022 11

47. Wu CY, Ghule SS, Liaw CC, Achudhan D, Fang SY, Liu PI. et al. Ugonin P inhibits lung cancer motility by suppressing DPP-4 expression via promoting the synthesis of miR-130b-5p. Biomedicine & pharmacotherapy = Biomedecine & pharmacotherapie. 2023;167:115483

48. Lin TH, Liu SC, Huang YL, Lai CY, He XY, Tsai CH. et al. Apelin facilitates integrin αvβ3 production and enhances metastasis in prostate cancer by activating STAT3 and inhibiting miR-8070. International journal of biological sciences. 2025;21:4117-28

49. Sarhan RS, El-Hammady AM, Marei YM, Elwia SK, Ismail DM, Ahmed EAS. Plasma levels of miR-21b and miR-146a can discriminate rheumatoid arthritis diagnosis and severity. BioMedicine. 2025;15:30-41

50. Yuan Y, Mu N, Li Y, Gu J, Chu C, Yu X. et al. TNF-alpha Promotes Synovial Inflammation and Cartilage Bone Destruction in Rheumatoid Arthritis via NF-kappaB/YY1/miR-103a-3p Axis. FASEB journal: official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2025;39:e70876

51. Wang YH, Su CH, Chen LC, Liu JF, Tsai CH, Fong YC. et al. miR-548aj-3p and miR-3127-3p suppress RANKL-facilitated inflammatory cytokines and catabolic factor in osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. International journal of medical sciences. 2025;22:3650-63

52. Bu X, Chen Z, Zhang A, Zhou X, Zhang X, Yuan H. et al. Circular RNA circAFF2 accelerates gastric cancer development by activating miR-6894-5p and regulating ANTXR 1 expression. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2021;45:101671

Author contact

![]() Corresponding authors: Chih-Hsin Tang, PhD; Email: chtangcmu.edu.tw. Chih-Yang, Lin PhD; E-mail: T016406skh.org.tw.

Corresponding authors: Chih-Hsin Tang, PhD; Email: chtangcmu.edu.tw. Chih-Yang, Lin PhD; E-mail: T016406skh.org.tw.

Global reach, higher impact

Global reach, higher impact