Impact Factor

ISSN: 1449-1907

Int J Med Sci 2013; 10(9):1085-1091. doi:10.7150/ijms.6003 This issue Cite

Research Paper

Utility and Stability of Transnasal Endoscopy for Examination of the Pharynx - A Prospective Study and Comparison with Transoral Endoscopy

Department of Gastroenterology and Nephrology, Graduate School of Medicine, Chiba University, Chiba, Japan.

Received 2013-2-1; Accepted 2013-6-18; Published 2013-7-3

Abstract

Objective: Transnasal endoscopy may be used to observe the head and neck part readily without excessive reflexes. We aimed to evaluate the utility and stability of transnasal esophagogastroduodenoscopy (TN-EGD) in comparison with transoral EGD (TO-EGD) for observation of the pharynx.

Study Design: Prospective study

Methods: A total of 497 patients received unsedated TN-EGD with a 5.5 mm diameter endoscope or unsedated TO-EGD with endoscopes of 6.5 mm, 7.9 mm and 9.2 mm diameter. The rate of completion of pharyngeal observation and numbers of gag reflexes and cough reflexes were recorded.

Results: TN-EGD was performed in 175 patients and TO-EGD was performed in 322 patients. Pharyngeal observation was completed in 173 patients (98.9%) in the TN-EGD group and 235 patients (73.2%) in the TO-EGD group, a significant difference (p<0.001). The TN-EGD group had a low rate of occurrence of gag reflex (0.57%), in contrast, 28.3% of the TO-EGD group had a gag reflex, a significant difference (p<0.01). Multivariable analyses revealed that the use of TN-EGD was the only predictive factor for completion of pharyngeal observation (p<0.0001).

Conclusions: TN-EGD is ideally suited to observation of the pharynx by unsedated EGD.

Keywords: Transnasal EGD, Transoral EGD, Pharynx, Cancer.

INTRODUCTION

The number of esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) procedure is increasing. Most such procedures are performed to examine the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum and, although the pharynx can also be observed, most physicians do not take the time to examine the pharynx. However, head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs), especially in the hypopharynx, usually are diagnosed at an advanced stage resulting in a poor prognosis.

Two aspects of endoscopy have been developing. One is obtaining a precise diagnosis of the lesion by magnifying endoscopy and image enhancement endoscopy (IEE). The other is reduction of the patient's discomfort during the examination. Sadative agents are used widely during transoral EGD (TO-EGD) to reduce the patient's discomfort from excessive reflex and anxiety, however, sedation itself has a cardiopulmonary complication and increases the time and operation of pre- and post-procedures, as well as the cost. Previous studies reported that the route of endoscopy is an important factor affecting the discomfort of endoscopy [1], that is, this may be reduced by transnasal EGD (TN-EGD), rather than TO-EGD.

We aimed, therefore, to evaluate the feasibility of TN-EGD, in comparison with TO-EGD, using three different diameter endoscopes for pharyngeal observation in an outpatient-based prospective group.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and Esophagogastroduodenoscopy — This study involved patients who came to Chiba university hospital, Kazusa Academia Clinic, Chiba or Chiba Social Insurance Hospital for health screening and were referred for diagnostic EGD from September 2009 to November 2011. Written consent for EGD was obtained before the examination. Patients were excluded from this study when they wished to receive sedation or had a history of undergoing sedated endoscopy. Patients in the TN-EGD group received nasal anesthesia by spraying a solution of 0.4% lidocaine and 0.118% tramazoline into the nostril. Patients in the TO-EGD group received throat anesthesia through 5 ml of 2% lidocaine viscous for 5 min. All EGD were performed with the patient in the left lateral recumbent position and sniffing head position. Examinations were performed by three experienced endoscopists who carried out both TO-EGD and TN-EGD.

This study was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of Chiba University School of Medicine. Informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Endoscopes — Four types of endoscope were used with the IEE (GIF-XP260N, GIF-XP260, GIF-PQ260, and GIF-Q260, Olympus Corp.) in this study. The GIF-XP260N, with a diameter of 5.5 mm, was used for TN-EGD; its resolution power being equal to the GIF-XP260. The GIF-XP260, GIF-PQ260, and GIF-Q260, with diameters of 6.5 mm, 7.9 mm, and 9.2 mm, respectively, were used for TO-EGD. Similar models are sold in the U.S. and Europe (Olympus Co., http://www.olympus-global.com/en/). The resolution power of the GIF-XP260 and GIF-XP260N are sufficient for routine EGD and those of the GIF-PQ260 and GIF-Q260 are superior to the GIF-XP260 and GIF-XP260N.

Pharyngeal observation — Pharyngeal observation was performed in a scheduled way, starting from the pharyngeal portion of tongue. In turn, we examined the posterior wall of the oropharynx, the right wall of the oropharynx, the epiglottis, the left wall of the oropharynx, the left wall of the hypopharynx, the posterior wall of the hypopharynx, the right wall of the hypopharynx, the right piriform fossa, the anterior wall of the hypopharynx and larynx and the left piriform fossa. When necessary, we requested appropriate vocalization during observation of the piriform fossa. When the examination was complete, we inserted the endoscope gently into the esophagus. All observations were made using IEE and we measured the time of pharyngeal observation from the start point to completion. When an excessive gag or cough reflex made the observation difficult, we stopped the observation of the pharynx immediately and inserted the endoscope into the esophagus because a severe gag and cough reflex might have caused severe complications and made it difficult to complete the procedure. Thus, we abandoned the examination of the pharynx once the patient had an excessive gag or cough reflex and, in such cases, we re-examined the pharynx after removing the endoscope from the esophagus. A gag or cough reflex which did not interfere the observation was recorded as a slight gag or cough reflex. The GIF-XP260N was used in Chiba University Hospital, and the GIF-XP260 and GIF-PQ260 were used in Kazusa Academia Clinic, and GIF-XP260N and GIF-Q260 were used in Chiba Social Insurance Hospital. Patients were not randomized, but endoscopes were distributed used randomly for the patients in each facility.

Evaluation Criteria — In this study, we evaluated following three criteria: (1) rates of completion of pharyngeal observation, (2) numbers of gag and cough reflexes and (3) observation time in the cases where the pharynx was examined completely.

Statistical Analysis — The baseline data are presented as mean ± SD. Differences in the values of clinical parameters between the two groups were analyzed by the unpaired t test and Chi-square test. Logistic regression analysis was used for statistical analyses, as appropriate, with the statistical program PASW statistics 18 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA); a p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Transnasal and Transoral Esophagogastroduodenoscopy — This study comprised included 497 patients (346 men and 151 women). TN-EGD was performed on 175 patients and TO-EGD was performed on 322 patients (Table 1a, Table 1b). There was no adverse event and insertion into the esophagus was successful for all patients in both groups. No case of epistaxis was documented in this study. No neoplasia was detected in either group.

Clinical Backgrounds of the Patients.

| All | TN-EGD | TO-EGD | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 497 | 175 | 322 | ||

| Age (years) | 53.2 ± 9.88 (29-79) | 54.2 ± 10.6 (32-79) | 53.3 ± 8.04 (29-79) | n.s.* | |

| Gender (M/F) | 346 / 151 | 113 / 62 | 232 / 89 | n.s.** | |

| Previous EGD (yes/no) | 405 / 92 | 127 / 48 | 266 / 45 | <0.001** | |

| Type of EGD | GIF-XP260N | ||||

| Diameter of EGD | 5.5 mm | 6.5 - 9.2 mm |

* unpaired t-test, ** chi-square test.

Details of TO-EGD.

| 6.5 mm | 7.9 mm | 9.2 mm | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GIF-XP260 | GIF-PQ260 | GIF-Q260 | |

| Number of patients | 167 | 77 | 78 |

| Age (years) | 51.8 ± 7.37 (34-75) | 51.7 ± 10.1(29-79) | 55.7 ± 11.9 (34-74) |

| Gender (M/F) | 128 / 39 | 61 / 16 | 44 / 34 |

| Previous EGD (yes/no) | 134 / 23 | 65 / 11 | 67 / 11 |

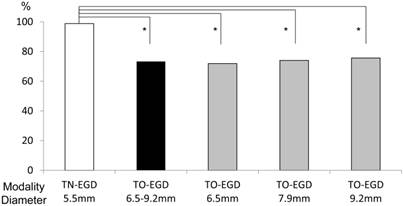

Rate of completion of pharyngeal observation — Rates of completion of pharyngeal observation in the TO-EGD and TN-EGD groups are illustrated in Figure 1. In the TN-EGD group, 173 of 175 patients (98.9%) received complete pharyngeal observation, compared to 235 of 322 (73.2%) patients in the TO-EGD group, a significant difference (p<0.001, chi-square test). The rates of completion of pharyngeal observation using the GIF-XP260 (diameter was 6.5 mm), GIF-PQ260 (7.9 mm) and GIF-Q260 (9.2 mm) were 71.9 %, 74.0 %, and 75.6 %, respectively, which did not show a statistical difference between these endoscopes in the TO-EGD group.

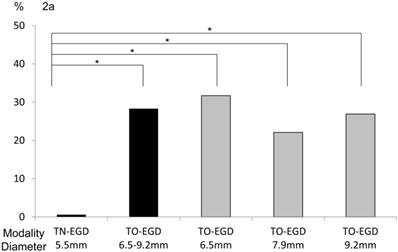

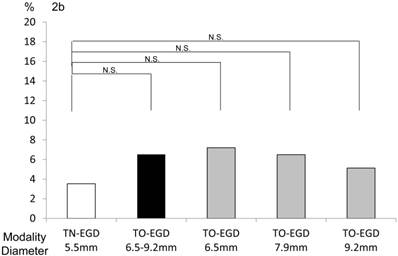

Numbers of gag and cough reflexes — The TN-EGD group had a low rate of occurrence of gag reflex (0.57 %). In contrast, 28.3% of the TO-EGD group had a gag reflex. There was a significant difference between the two groups (p<0.01, chi-square test, Figure 2a). In detail, the occurrence rates of gag reflex with the GIF-XP260 (6.5 mm), GIF-PQ260 (7.9 mm), and GIF-Q260 (9.2 mm) were 31.7%, 22.1%, and 26.9%, respectively. There was no significant difference among the endoscopes in the occurrence of cough reflex (Figure 2b). Specifically, the rates of occurrence of cough reflex in the TN-EGD, TG-EGD, GIF-XP260 (6.5 mm), GIF-PQ260 (7.9 mm), and GIF-Q260 (9.2 mm) groups were 3.5%, 6.5%, 7.2%, 6.5%, and 5.1%, respectively.

Rates of completion of pharyngeal observation. 98.9% received a complete pharyngeal observation in the TN-EGD group and 73.2% of the TO-EGD group received a complete pharyngeal observation (*p<0.001, chi-square test). TN-EGD; transnasal EGD, TO-EGD; transoral EGD.

Occurrence rates of (a) gag reflex and (b) cough reflex. (a) The occurrence rate of a gag reflex was 0.57% in the TN-EGD group and 28.3% in the TO-EGD group and there was a significant difference between the TN-EGD and TO-EGD groups (*p<0.01, chi-square test). (b) The occurrence rates of a gag reflex with the GIF-XP260 (6.5 mm diameter), GIF-PQ260 (7.9 mm) and GIF-Q260 (9.2 mm) were 31.7%, 22.1% and 26.9%, respectively (N.S.). TN-EGD; transnasal EGD, TO-EGD; transoral EGD, N.S.; not significant.

Factors Associated with completion of pharyngeal observation — A comparison of characteristics between the completely and incompletely observed groups is shown in Table 2. There were significant differences in age, types of EGD and diameter of EGD. Multiple logistic regression analysis of factors associated with completion of pharyngeal observation (Table 3) reveals that the use of TN-EGD was the only predictive factor for completion of pharyngeal observation (odds ratio [OR] 32.6, 95% Confidence interval [CI]: 7.7-138.0, p<0.0001) and gender, age, diameter of endoscope and previous experience of EGD were not associated with successful pharyngeal observation.

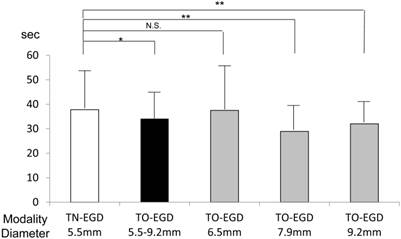

Time for observation of the pharynx — We analyzed the time required for pharyngeal observation only for the patients in whom the examination was carried out completely. In Figure 3, the time for pharyngeal observation is shown for each endoscopy method. The duration of pharyngeal examination in the TN-EGD group was greater than for the other endoscopy methods. Table 4 shows multiple logistic regression analysis of factors associated with the time of pharyngeal observation. A long observation was defined as over 35.8 seconds which was the average time for examination of the pharynx. Slight reflexes which did not interfere with the examination occurred in 6.2% with TO-EGD and 3.4% with TN-EGD and were not a determining factor. This analysis reveals that use of TN-EGD was the only predictive factor for an extended time of pharyngeal observation (OR 1.76, 95% CI: 1.16-2.67, p=0.007).

Observation time for examining the pharynx. The time for successful pharyngeal examination was greater for the TN-EGD and GIF-XP260 (6.5 mm) groups. Bars are mean ± SD. **p<0.01, *p<0.05, unpaired t-test). TN-EGD; transnasal EGD, TO-EGD; transoral EGD, N.S.; not significant.

Comparison of the characteristics of the complete and incomplete groups for examination of the pharynx.

| Complete | Incomplete | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) (range) | 53.7 ± 10.2 (29-79) | 51.1 ± 8.1 (34-70) | 0.011* |

| Gender (M/F) | 288 / 121 | 58 / 30 | n.s.** |

| Previous EGD (yes / no) | 317 / 81 | 76 / 10 | n.s.** |

| TN-EGD / TO-EGD | 173 / 236 | 2 / 86 | <0.001** |

| Diameter of the endoscope (5.5 mm / 6.5 mm / 7.9 mm / 9.2 mm) | 173 / 120 / 57 / 59 | 2 / 47 / 20 / 19 | <0.001** |

* unpaired t-test, ** chi-square test.

Analysis of the predictive factors for complete observation of the pharynx.

| Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio | 95% CI | p value | Odds ratio | 95% CI | p value | ||

| Endoscopic modality | |||||||

| TN-EGD (vs. TO-EGD) | 31.3 | 7.4-132.2 | <0.0001 | 32.6 | 7.7-138.0 | <0.0001 | |

| Diameter | |||||||

| Small caliber (vs. large caliber) | 2.01 | 1.25-3.22 | 0.038 | 0.86 | 0.52-1.43 | 0.57 | |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male (vs. female) | 1.23 | 0.76-2.00 | 0.41 | ||||

| Age | |||||||

| Elderly* (vs. young) | 1.61 | 1.02-2.57 | 0.043 | 0.62 | 0.37-1.02 | 0.058 | |

| Previous EGD | |||||||

| No (vs. yes) | 2.17 | 1.04-4.50 | 0.038 | 1.73 | 0.78-3.82 | 0.18 | |

* Elderly was defined as over 53 years old which was the average of the patients. CI, confidence interval.

Analysis of factors for long observation in the accomplished group.

| Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio | 95% CI | p value | Odds ratio | 95% CI | p value | ||

| Endoscopic modality | |||||||

| TN-EGD (vs. TO-EGD) | 1.67 | 1.12-2.50 | 0.012 | 1.76 | 1.16-2.67 | 0.007 | |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male (vs. female) | 0.78 | 0.76-1.83 | 0.46 | ||||

| Age | |||||||

| Young (vs. elderly) | 1.30 | 0.52-1.16 | 0.21 | ||||

| Previous EGD | |||||||

| Yes (vs. no) | 1.22 | 0.73-2.02 | 0.45 | ||||

| Reflex | |||||||

| Slight gag reflex | 1.37 | 0.55-3.46 | 0.50 | ||||

| Slight cough reflex | 0.60 | 0.011-3.11 | 0.54 | ||||

* Elderly was defined as over 53 years old which was the average of the patients. CI, confidence interval.

DISCUSSION

Unsedated TN-EGD is considered to be an attractive alternative to conventional sedated TO-EGD because it can reduce patient discomfort and cost, avoid the cardiopulmonary complications associated with sedation, and make unnecessary a period of recovery. After examination, patients can drive a car or return to work[2,3]. Generally, TN-EGD can be accomplished without a severe gag reflex. We carried out this study to test the hypothesis that TN-EGD may enable adequate examination of the pharynx. This study had the limitations of a non-randomized, non-crossover design and various factors, such as anesthetic delivery, insertion route, diameter of the endoscopes, and variation in the skills of endoscopists could impact on the outcome. In that sense, further randomized and crossover studies are needed.

Some studies have reported that the use of a transoral, small-caliber endoscope without sedation leads to a reduction of patient discomfort during EGD[4-6] and that unsedated TN-EGD also produces less discomfort than conventional TO-EGD[7-9]. In addition, other studies have reported that TN-EGD is more tolerable than small-caliber EGD[10-12]. Some studies reported that the diameter of the endoscope was an important factor in patients' discomfort[6,13] but others have suggested that the route was the determining factor [1]. Our study showed that the difference in endoscope diameter for TO-EGD was not a determining factor for the occurrence of the gag reflex, and that the route was the only determining factor. This is because the tongue base is contacted and compressed during TO-EGD but the instrument does not contact the tongue base during TN-EGD, which results in less gag reflex[1]. A serious limitation of our study is that the number of transoral and transnasal EGDs performed differ because it was exploratory in nature and we did not determine the numbers of patients for each procedure in advance using a statistical approach.

Several reports have addressed the feasibility of TN-EGD for the head and neck oncology patients [14,15] but no other study has documented the utility of TN-EGD for observation of the pharynx by comparing it TO-EGD. In this study, we report for the first time that TN-EGD achieved a higher rate of completion of examination of the pharynx than TO-EGD, with statistical significance. Univariable and multivariable analyses of predictive factors for successful pharyngeal observation were performed. The univariable analysis revealed that age and TN-EGD were predicting factors. This result is consistent with our impression that elderly people tend to have less reflex than younger people. The multivariable analysis showed that TN-EGD was the only predictive factor for successful pharyngeal observation. Although we expected that the patients who had experienced previous EGD would show less reflex than inexperienced patients, previous experience of EGD was not a significant factor. These results suggest that TN-EGD could be used for safe and complete examination of the pharynx.

In this study, the average time for pharyngeal examination in the successful TN-EGD group was significantly longer than that for the successful TO-EGD group. This result suggests that TN-EGD causes fewer reflexes, which provides sufficient time to examine the pharynx. On the other hand, TO-EGD caused the physicians to hurry in fear of having to cease examination because of severe reflexes. As a result, the time of pharyngeal examination might be shorter for the TO-EGD group.

The development of IEE has played an important role in the diagnosis of neoplasms of the colon, esophagus and stomach. Some reports have clarified the effectiveness of IEE and helped us to recognize superficial neoplastic lesions in the head and neck region[16-19]. TN-EGD with IEE also has been reported to be useful for the detection of pharyngeal neoplasms at an early stage [20,21]. Therefore, we used IEE routinely for pharyngeal observation in this study although no pharyngeal cancer was detected. This study did not determine whether TN-EGD can detect pharyngeal lesions more effectively than TO-EGD. In Japan, the number of patients with pharyngeal lesion is quite small compared to the number of patients with gastric cancer and esophageal cancer; annually, 213 people per 100,000 are newly diagnosed as stomach and/or esophageal cancer whilst 7.2 people per 100,000 are newly diagnosed as oral and/or pharyngeal cancer. If the study had been carried out on a high risk group, it might have been possible to confirm the value of TN-EGD for the detection of pharyngeal cancer. The image quality of GI endoscopes is superior to those of laryngoscopes, and the numbers of patient referred for EGD are quite high compared to those for laryngoscopy because most of them did not have any pharyngeal symptoms at the time of their EGD examination. On the other hand, a laryngoscope is often used for patients with pharyngeal symptoms, so we think it is very meaningful if GI endoscopists detect asymptomatic head and neck lesion during EGD. It is also very difficult to evaluate the detection ability of TN-EGD, TO-EGD and the laryngoscope but we think a comparative study of the laryngoscope and EGD and confirmation of detection in patients with malignant tumors would be very meaningful. Further analysis of the ability of TN-EGD to detect pharyngeal lesions is needed. A crossover study of TO-EGD versus TN-EGD using a TN endoscope is needed for thorough comparison of the TO and TN routes. However, our current study was based on practical medicine and was limited study in terms of the statistical analysis. Various factors such as anesthetic delivery, insertion route, diameter of the endoscopes, and variation in the skills of the endoscopists could influence the result and these may be limitations of our study. In conclusion, unsedated TN-EGD seems to be one of the most reliable methods for examination of the pharynx with minimal discomfort. Our present study was exploratory and not randomized. Further randomized and crossover studies are needed to clarify the value of TN-EGD for pharyngeal observation.

ABBREVIATIONS

EGD: esophagogastroduodenoscopy

SCC: squamous cell carcinoma

IEE: image enhanced endoscopy

TO-EGD: transoral EGD

TN-EGD: transnasal EGD

OR: odds ratio

CI: confidence interval

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff of Kazusa Academia Clinic and Chiba Social Insurance Hospital. and are grateful to Dr. Kunio Kimura (Chiba Social Insurance Hospital).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.

References

1. Dumortier J, ponchon T, Scoazec JY. et al. Prospective evaluation of transnasal esophagogastroduodenoscopy: feasibility and study on performance and tolerance. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:285- 291

2. Thota PN, Zuccaro G Jr, Vargo JJ II. et al. A randomized prospective trial comparing unsedated esophagoscopy via transnasal and transoral routes using a 4-mm video endoscope with conventional endoscopy with sedation. Endoscopy. 2005;37:559-65

3. Dean R, Dua K, Massey B. et al. A comparative study of unsedated transnasal esophagogastroduodenoscopy and conventional EGD. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:422-4

4. Trevisani L, Cifalà V, Sartori S. et al. Unsedated ultrathin upper endoscopy is better than conventional endoscopy in routine outpatient gastroenterology practice: A randomized trial. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13(6):906-911

5. Sorbi D, Gostout CJ, Henry J. et al. Unsedated small-caliber esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) versus conventional EGD: a comparative study. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:1301-7

6. Horiuchi A, Nakayama Y. Unsedated ultrathin EGD by using a 5.2-mm-diameter videoscope: evaluation of acceptability and diagnostic accuracy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:868-73

7. Stroppa I, Grasso E, Paoluzi OA. et al. Unsedated transnasal versus transoral sedated upper gastrointestinal endoscopy: A one-series prospective study on safety and patient acceptability. Digestive and Liver Disease. 2008;40:767-775

8. Birkner B, Fritz N, Schatke W. et al. A Prospective Randomized Comparison of Unsedated Ultrathin Versus Standard Esophagogastroduodenoscopy in Routine Outpatient Gastroenterology Practice: Does It Work Better through the Nose? Endoscopy. 2003;35:647-651

9. Zaman A, Hahn M, Hapke R. et al. A randomized trial of peroral versus transnasal unsedated endoscopy using an ultrathin videoendoscope. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:279-84

10. Preiss C, Charton JP, Schumacher B. et al. A randomized trial of unsedated transnasal small-caliber esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) versus peroral small-caliber EGD versus conventional EGD. Endoscopy. 2003;35(8):641-6

11. Craig A, Hanlon J, Dent J. et al. A comparison of transnasal and transoral endoscopy with small-diameter endoscopes in unsedated patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:292-6

12. Murata A, Akahoshi K, Sumida Y. et al. Prospective randomized trial of transnasal versus peroral endoscopy using an ultrathin videoendoscope in unsedated patients. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2007;22:482-485

13. Mulcahy HE, Riches A, Kiely M. et al. A prospective controlled trial of an ultrathin versus a conventional endoscope in unsedated upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Endoscopy. 2001;33:311- 316

14. Postma GN, Bach KK, Belafsky PC. et al. The role of transnasal esophagoscopy in head and neck oncology. Laryngoscope. 2002Dec;112(12):2242-3

15. Wang CP, Lee YC, Yang TL. et al. Application of unsedated transnasal esophagogastroduodenoscopy in the diagnosis of hypopharyngeal cancer. Head Neck. 2009Feb;31(2):153-7

16. Nonaka S, Saito Y. Endoscopic diagnosis of pharyngeal carcinoma by NBI. Endoscopy. 2008;40:347-51

17. Takano JH, Yakushiji T, Kamiyama I. et al. Detecting early oral cancer: narrowband imaging system observation of the oral mucosa microvasculature; Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2010;39:208-213

18. Muto M, Minashi K, Yano T. et al. Early detection of superficial squamous cell carcinoma in the head and neck region and esophagus by narrow band imaging: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(9):1566-72

19. Nonaka S, Saito Y. Endoscopic diagnosis of pharyngeal carcinoma by NBI. Endoscopy. 2008;40:347-351

20. Watanabe A, Tsujie H, Taniguchi M. et al. Laryngoscopic detection of pharyngeal carcinoma in situ with narrowband imaging. Laryngoscope. 2006;116:650-654

21. Ugumori T, Muto M, Hayashi R. et al. Prospective study of early detection of pharyngeal superficial carcinoma with the narrowband imaging laryngoscope. Head Neck. 2009;31:189-194

Author contact

![]() Corresponding author: Makoto Arai M.D. Department of Gastroenterology and Nephrology, Graduate School of Medicine, Chiba University, Inohana 1-8-1, Chiba-City, 260-8670, Japan. TEL: +81-43-226-2083 FAX: +81-43-226-2088 E-mail: araim-cibac.jp.

Corresponding author: Makoto Arai M.D. Department of Gastroenterology and Nephrology, Graduate School of Medicine, Chiba University, Inohana 1-8-1, Chiba-City, 260-8670, Japan. TEL: +81-43-226-2083 FAX: +81-43-226-2088 E-mail: araim-cibac.jp.

Global reach, higher impact

Global reach, higher impact